With the gathering of hundreds of people for a march in Monterey Bay every year, a piece of California history is no longer buried deep under the scenery of the coast.

The tourist hot spot, known for its scenic beauty and world-famous aquarium, was founded by the Spanish in the late 18th century, even becoming the capital of Alta California (a geographic area that now encompasses parts of California, Nevada, Utah and Arizona) for a period. But the city has a hidden history.

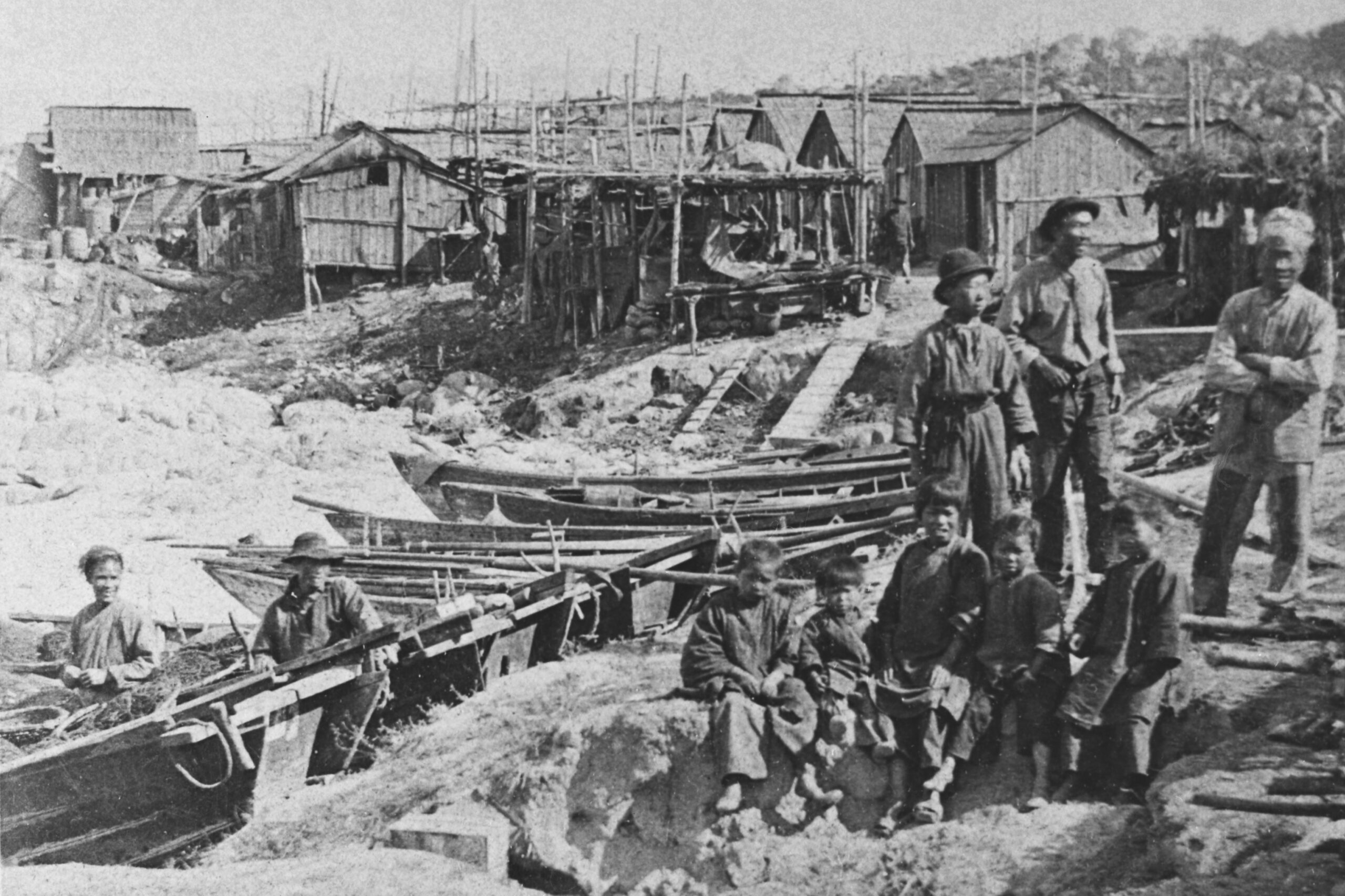

In the decades after California became a state, Monterey Bay was a safe harbor for hundreds of early Chinese immigrants who came to America by boat during the mid-19th century. Rebuilding their homes and their livelihoods, they started the first fishing industry in the area, catching abalone, oysters, mussels and other varieties of fish.

However, anti-Chinese sentiment soared, and the Point Alones village, the largest Chinese fishing settlement in California, was not spared the violence. In 1906, a suspicious fire burned down the once-thriving village, destroying the fishing community’s hard-fought achievement and scattering hundreds of Chinese residents elsewhere.

There has never been any form of financial restitution. And the humiliation the episode left among its victims and their descendants has endured for more than a century.

The Anti-Chinese Movement

Residents of the Monterey Peninsula have only recently begun to reckon with the past. Last year, Pacific Grove—a bed-and-breakfast-filled city of 15,000 people that borders Monterey where the village was located—issued an official apology to the local Chinese community and the descendants of the Chinese fishing village for what happened in 1906.

Specifically, the city council passed a resolution stating the city “apologizes to Chinese settlers, citizens, immigrants and their descendants, who came to Pacific Grove before and after it became a City, and were the victims of institutional racism, prejudice and discrimination.”

According to the resolution, the fire started on May 16, 1906. Since the Chinese residents couldn’t extinguish the fire, they had to rush to save their belongings while “hundreds of spectators watched, cheered the flames and looted those belongings.”

A day after the fire, local looters came back and picked through “warm ashes for village belongings.”

The incident happened barely four weeks after the great earthquake and fire of 1906 destroyed large swaths of San Francisco, including its Chinatown. Though both Chinese establishments were torn down, the reasons are clearly different: One was a natural disaster, the other arson driven by anti-Chinese racism.

Unlike San Francisco’s Chinatown, which was rebuilt after the earthquake in spite of widespread racism, any attempt to reconstruct Monterey Bay’s Chinese fishing community met with stiff resistance.

The Pacific Improvement Company, a major railroad interest and resort developer, joined the cause of erasing the Chinese American presence. After the fire, the company erected fences, posted guards, forcibly removed residents who refused to leave and tore down any attempts at rebuilding.

“[A]fter the last remaining village resident, Quock Tuck Lee, left for Monterey, the destruction of the Point Alones Village, the removal of its men, women, children and families, and the eradication of their community, heritage and history was complete,” the resolution states.

Similarly, San Jose’s historic Chinatown was also burned down by suspicious fires during the anti-Chinese movement in the late 19th century.

In recent years, other cities also issued official apologies to the Chinese community, including San Francisco and San Jose. In 2022, Pacific Grove also ended its decades-long tradition called the “Feast of Lanterns,” whose use of yellowface makeup and theatrical marriage ceremonies were criticized for cultural appropriation and racism.

Walk of Remembrance

On May 13, the 12th annual “Walk of Remembrance” attracted hundreds of participants at the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History, the starting point of the parade to honor and remember the early Chinese fishermen who lived in the Monterey Bay fishing village prior to the fire.

Many of them were holding black-and-white photos showing the faces of the Chinese village residents during the walk. People marched from the museum to the Hopkins Marine Station, the historic site of the now-disappeared village.

Brandon Sabado, a sixth-generation descendant of Point Alones, gave a speech and thanked the participants for remembering this history.

“It fills me with honor that you're all here,” Sabado said, “to celebrate our shared history and the ancestors from the Chinese fishing village.”

But the bigger name among the crowd was Sabado’s mother, Gerry Low-Sabado, a tireless fighter for Monterey Bay Chinese history who helped start this annual tradition. A Monterey Bay native, Low-Sabado found out later in life about the fishing village's history and her own family ties to the early immigrants, which turned her into a passionate activist whose efforts were recognized nationally. She was the great-granddaughter of Quock Mui, who was born in 1859 in the village and is believed to be the first documented American-born Chinese woman.

Sadly, Low-Sabado died in 2021 at the age of 71. Randy Sabado, her husband and Brandon’s father, has carried on the torch and served as the event’s organizing committee chair.

Descendants Speak Up

Dozens of village descendants, mostly multigenerational Chinese Americans, met up at the historic site after the May 13 walk to share their stories.

It was the first time they’d held such a large gathering since the pandemic, so they put a gigantic family tree on the wall so that everyone could trace their lineage.

Janet Chang, a San Francisco native, was holding her grandmother Jeanie Quock Chan’s photo. Chang said her grandmother was born in the village in 1880 and moved to the Marin County community of Tiburon with her children after the 1906 fire to work on farms.

“After my grandfather died, [my grandmother] moved to San Francisco Chinatown,” Chang said. She, her mother and her children are all San Francisco “ABC,” or “American-born Chinese.”

Standing with her cousins, Chang said the family found out about the fishing village ties and history “a little bit here and a little bit there.” She hoped society would remember that history to help promote immigrants’ rights.

“Most of them come for a better life for themselves and their family,” Chang said. “We should remember it in relation to immigrants today.”

Brandon Sabado urged more descendants to investigate their ancestry and their connections to this chapter of California’s past.

“I encourage everyone to come share your stories,” he said. “So we can continue celebrating for the Chinese fishing village.”