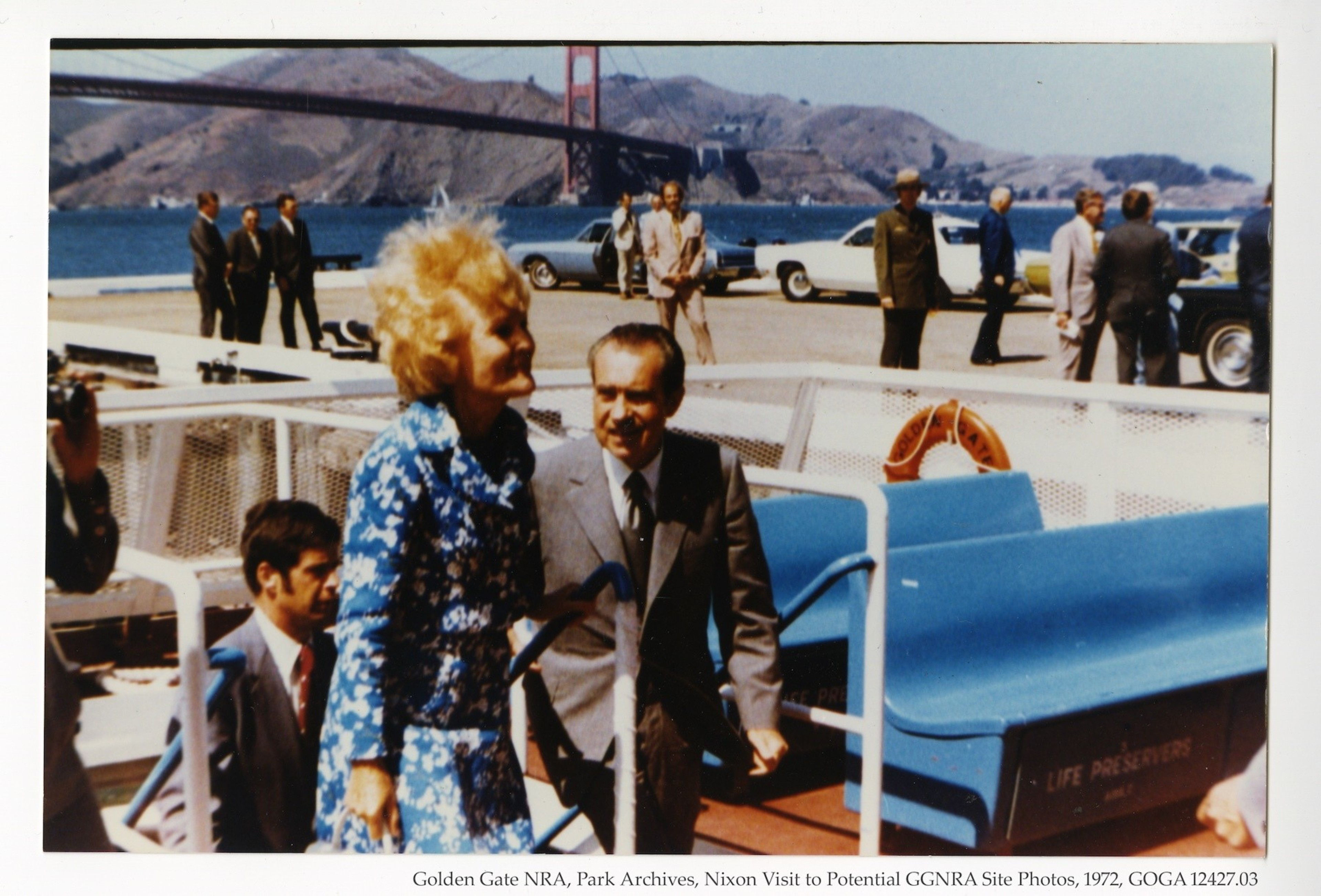

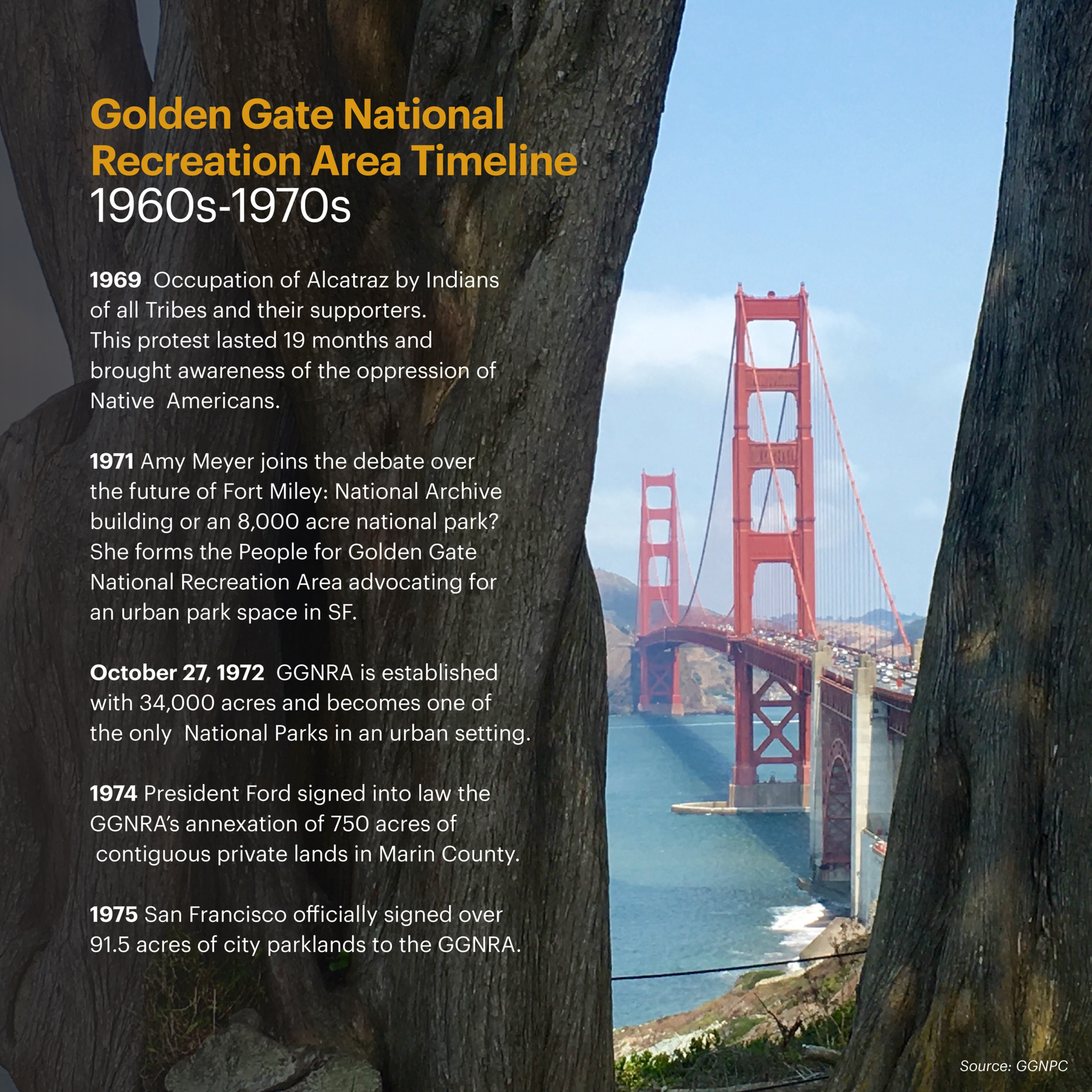

More than 6-in-10 San Franciscans were not yet born when President Richard Nixon signed a bill to add the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (opens in new tab) (GGNRA) to the National Park System on Oct. 27, 1972.

The GGNRA broke new ground from Day One because there had never been a national park so close to an urban area. And as the park kicks off its year of 50th birthday celebrations (opens in new tab), it is important to recognize the female leaders (opens in new tab) who shaped its development.

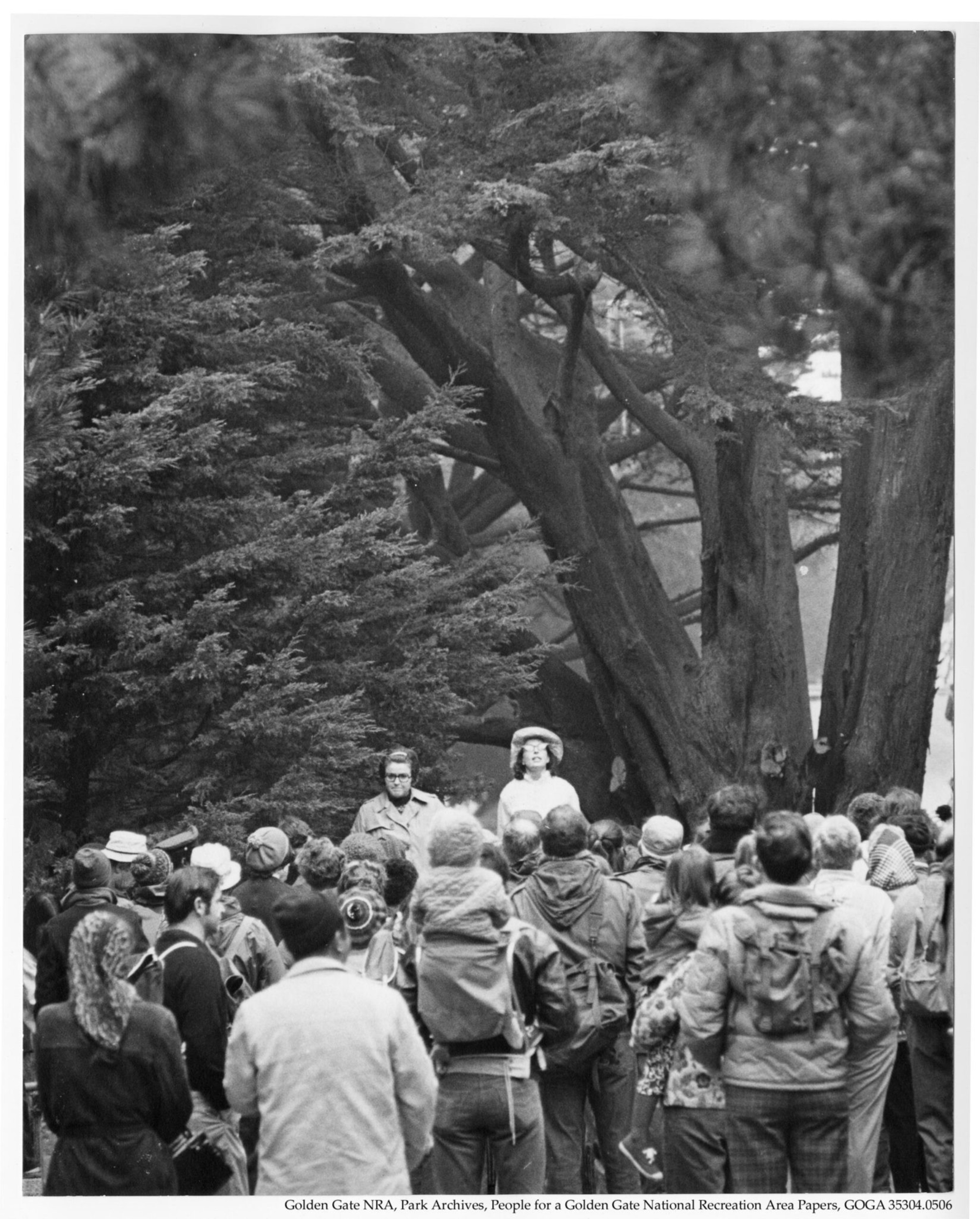

The entire park was brought to life in the 1960s around the kitchen table of Amy Meyer (opens in new tab), known as the “Mother of the GGNRA.” She heard the debate over whether a decommissioned Fort Miley should become a National Archive building or a park, and she galvanized a community effort with the goal to create an 8,000-acre park.

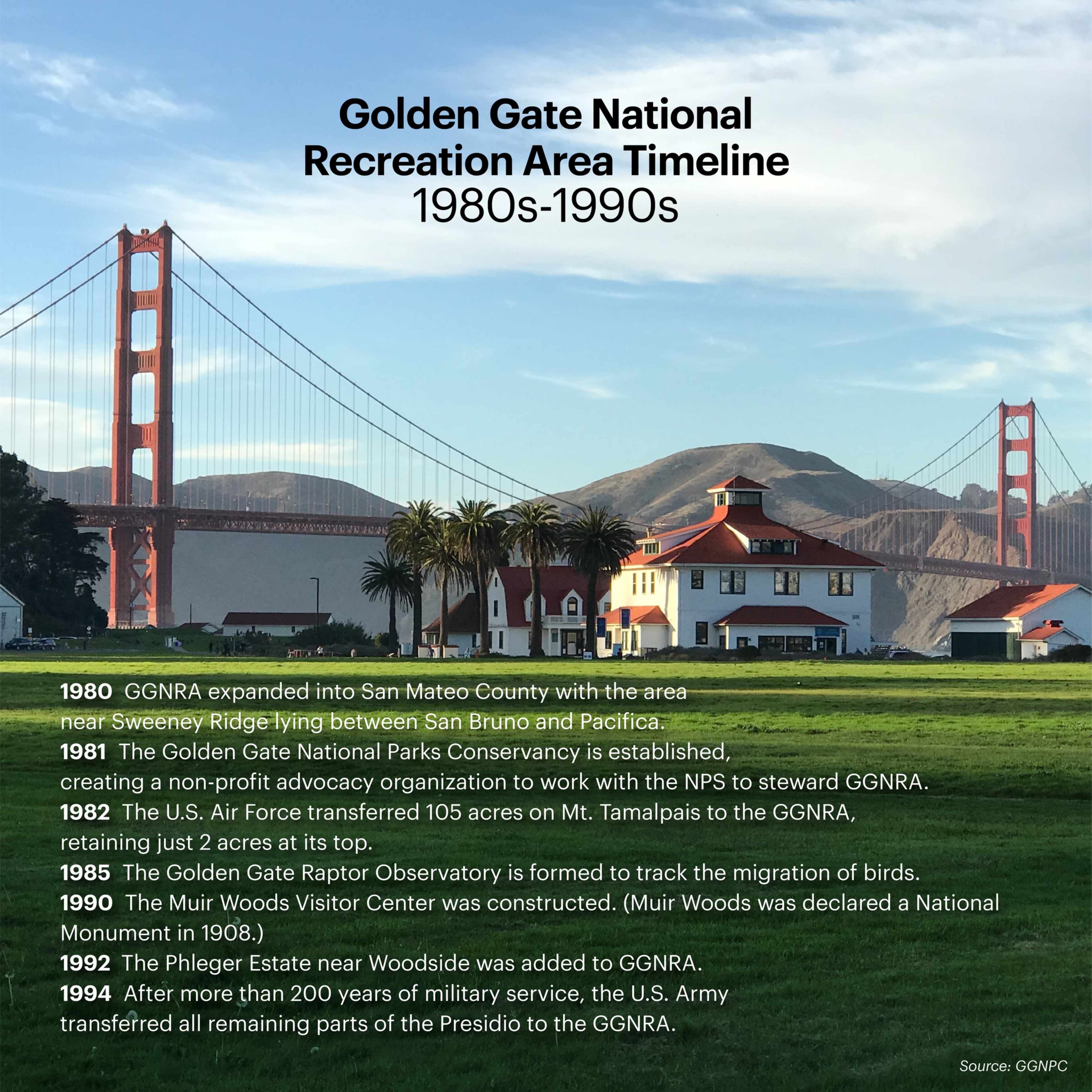

Fifty years later, Meyer and her backers smile upon the 82,000 acres of GGNRA wilderness (opens in new tab) that now stretch from Olema Valley in Marin County down to the Phleger Estate near Woodside. Meyer remains an active supporter of the park, as does one of her early partners, longtime ranger Mia Monroe (opens in new tab). (Click here to get The Standard’s bucket list of must-do SF activities in the park.)

As president and CEO of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy (opens in new tab), Christine S. Lehnertz leads the nonprofit partner of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

Lehnertz has spent her career (opens in new tab) advocating for the environment, including leadership roles with the National Park Service holding superintendent positions in famed parks like Yellowstone, Grand Canyon and the GGNRA, too. Prior to the NPS, she spent 17 years with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

As the nonprofit partner of the GGNRA, the Parks Conservancy raises funds to enhance the park, including the new Tunnel Tops park, the 20th anniversary of Crissy Field (opens in new tab) in 2021, and the Black Point Historic Gardens Trail (opens in new tab). The group works closely with the National Parks Service (led locally by GGNRA superintendent Laura Joss until her retirement earlier this year) and the Presidio Trust (led by Jean Fraser) to preserve, improve and restore the park.

As the GGNRA begins its celebration of 50 years next week, The Standard spoke with Lehnertz about what drives the Parks Conservancy’s mission to “activate” its national parklands.

Growing up, what pushed you to pursue a career in the outdoors and then the National Park Service?

I grew up in Colorado in a deeply outdoors culture and always had a deep sense of belongings in the outdoors. When my mom kicked us out of the house, it was a happy time for us kids.

I was into science in high school, and when I saw that you could actually apply it to land management and parks and make it a career, I was tickled.

Do you think the founders of the GGNRA would be happy with the progress you’ve achieved since its founding 50 years ago?

I think that the founders would be very impressed with what they see today. The Marin Headlands remain protected and have been enhanced ecologically, which was one of the original drivers of the project. In fact, Amy Meyer, the “mother” of the parks, is still active today and continues to provide input for the protection and preservation of the park.

How is your work at the nonprofit Parks Conservancy different from what you did when you were the superintendent of the park?

The Park Conservancy’s position as a nonprofit partner to the park lends itself to creativity and innovation and a little bit less bureaucracy, which is a great gift to me at this stage of my career. I can work with my wonderful colleagues in federal service and in state and county government to take their mission and amplify it to get things done that aren’t in the regular budget appropriations from Congress. It allows us to take their goals above and beyond what they envisioned.

We can provide products and convene partners to make this happen. Most of my job is conversations with community members, park partners, dreamers and certainly with elected officials to connect people and ideas with resources.

What is the difference between advocating for an urban park like GGNRA vs one like Grand Canyon or Yellowstone? For example, you were part of the National Park Service team that managed the controversy of allowing off-leash dogs in some parts of the park.

Yes, and I was always a dog owner through it all!

I think the piece that ties every national park together is the goal of preserving something that is of significance to the nation and every person in the U.S. To a national park in an urban setting, the gift is the community of people living nearby.

While some people think of a Yellowstone or Grand Canyon visit as something on their bucket list to experience only once in a lifetime, an urban park can get deep love and familiarity from the people who live closest to the park.

The location builds in a community and coalition of park supporters. In fact, we wonder whether some visitors even know they’re in a national park here. They might go to Lands End all the time to watch the sunset but may not know that there is a national park in their neighborhood and don’t know how significant it is to the whole country.

During the Tunnel Tops opening, you spoke about “activating” national park spaces. Can you explain what you mean by that and how that effort is going with Tunnel Tops?

When we talk about activating national parklands, we want to take the land and make it relevant to what a community member or neighborhood needs. Just understanding the national significance of the land does not activate it for every person. But if we are good listeners, we can hear what the community needs and design an experience for them.

So instead of presenting the community with a design and asking, “What do you think?” It’s a co-designing process: Everyone involved has a pencil, and everyone gets to do the drawing.

For Tunnel Tops, community members said they wanted to have things like hip-hop and Korean dance and so we brought the space to life with the interests of people in the adjacent communities.

In the first three months, Tunnel Tops has received hundreds of thousands of visitors—tens of thousands of kids have played in the outdoor playscape alone. The park has exceeded any expectation of the amount of fun that would take place there.

Can you speak to how GGNRA is using its role as an urban national park to enhance environmental education?

The Crissy Field Center is 21 years old now. It was a leader in the environmental education space when it started and that continues today. The Presidio’s governing partnership—[the Presidio Trust, the National Park Service and the Parks Conservancy]—is working together for the first time in this remodeled creative space, offering opportunities to grow through youth education.

This experience becomes a springboard for kids to grow into a green workforce, bringing what they learned here into their jobs and lives.

What is your next “dream project” for the GGNRA?

The interesting thing about having been the superintendent is that I built a dream list seven years ago for the GGNRA.

At the top of my list is activating the parklands near Sweeney Ridge, Mori Point, Milagra Ridge and Rancho Corral de Tierra. We are working with the community to hear what they are interested in in terms of trails there.

Another big dream is to revitalize the ecosystem in which Muir Woods sits. We want to preserve the larger ecosystem around the park and renew the redwoods without impacting them as much.

The early years of the NPS were about moving people directly to the most popular spots, but that was bad for the environment of those areas. We want to be sure the next era of tourism doesn’t further degrade these areas.

What do you think the next 50 years will look like for the GGNRA?

One of the things we learned during the pandemic is that parks can just be there for people. And now I’d like to understand our opportunities to activate the park differently and learn more about what a “post-pandemic outdoor experience” can be.

In the next 50 years, I’d like to see the 8 million people in the Bay Area come over and experience the magic of a national park in an urban area. We have lots of space for people to come and enjoy it here.

I hope everyone in the Bay Area feels like they belong in a national park. This effort starts with the youth of San Francisco, an opportunity like our library program, for example, which brings in multigenerational families. The kids come in through our educational offerings and then the shuttles [to the Presidio from branch libraries around the city] provide them the agency and inspiration from the land that so many of us take for granted to come back to the park and bring their family members.

What is your favorite place in the park?

Looking at the Golden Gate Bridge, you’ll see an arch constructed over Fort Point. It is what’s called a Third Order fort, and it’s the only one on the West Coast. When bridge engineer Joseph Strauss heard that it would be demolished, he knew he couldn’t let it happen. So he designed an arch structure (opens in new tab) over it to stand as a warm embrace of that Civil War history. To me, it is a sign that the preservation of that structure and the progress of San Francisco didn’t have to collide.

When you walk through the doors of Fort Point, you literally hear the life of the fort still there. There are crazy thick walls and crazy winds inside. I read once that when soldiers got sick of Fort Point, they took them to Alcatraz to warm up!

A favorite trail? We have 250 trails (opens in new tab)—and every single one just makes me happy.