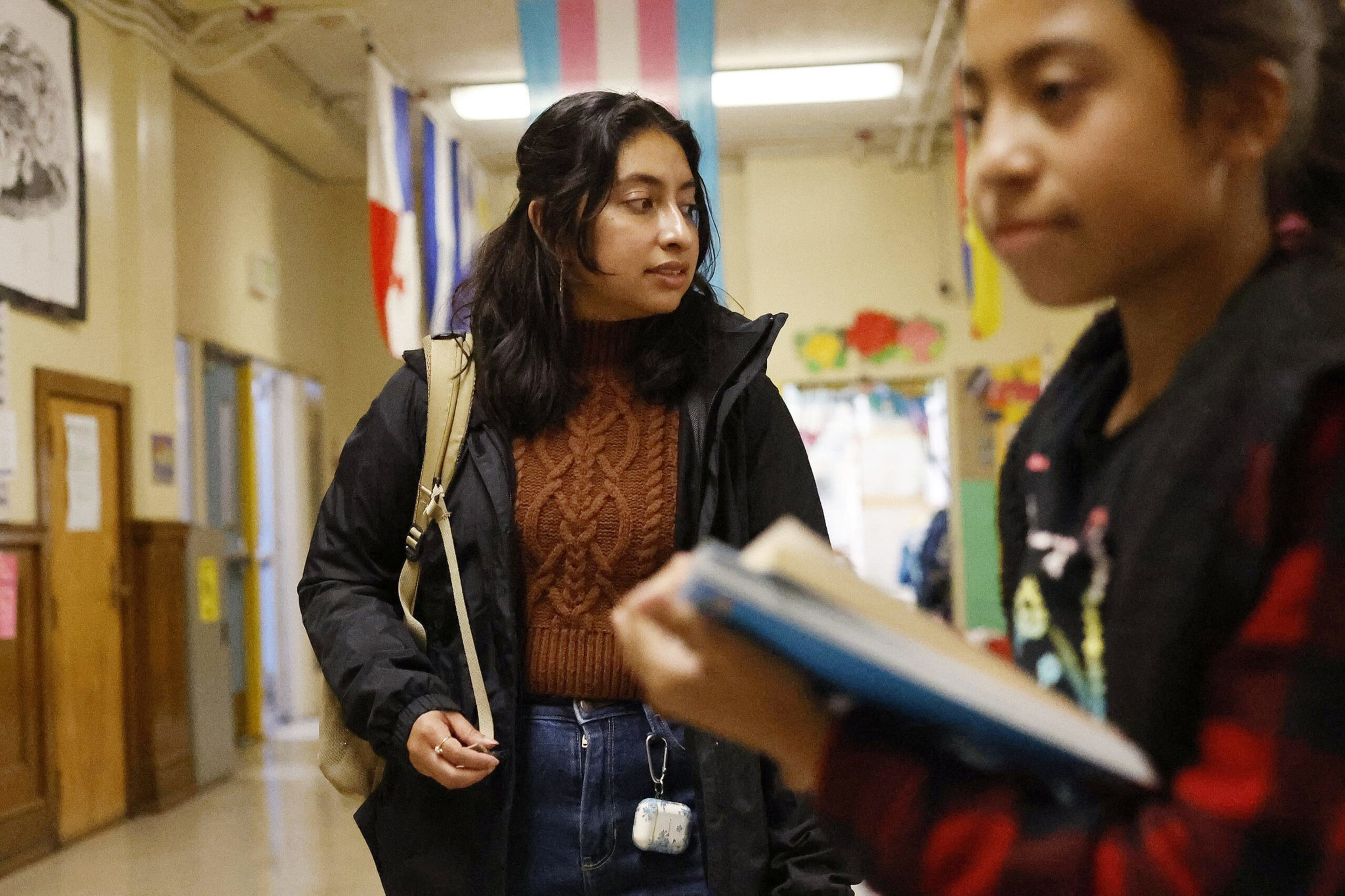

Through tutoring a student with autism at her former high school, San Francisco native Maria Guerrero knew teaching was the right purpose for her.

Her dream was just starting to take off last fall when she became a sixth grade English and social studies teacher at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Academic Middle School near Bayview-Hunters Point, where she was raised.

But almost three months into her new career, Guerrero’s onboarding paperwork still wasn’t finalized—which meant she still hadn’t been paid, a situation scores of district staff are painfully familiar with. Further, she said she wasn’t given a district email and access to parent communication platforms despite sending multiple emails a week to try to resolve these issues. Often, she received nothing more than an automatic reply.

Essentially, she was working for free.

“I just felt so ill-prepared,” Guerrero told The Standard. “The outside forces made it very difficult for me to reach my full potential as an instructor. Dealing with the bureaucracy was hard.”

Guerrero said she was eventually offered a loan check, but that didn’t sit right with her. Before the money ultimately came through, she made the difficult decision to leave the school in October out of self-preservation.

This was despite loving every minute she spent with her students and getting to know their families, she said. The month that followed was filled with anger and sadness.

“I missed my students and felt like I failed them,” Guerrero said. “I felt like I was going against my values and everything I stood for. However, I can’t be there for my community if I’m not there for myself first.”

Her human resources nightmare didn’t end there. A mentor inspired Guerrero to keep going, so she applied for a reading specialist position at a San Francisco public school in January. Although educators can begin working in city classrooms before the full hiring process is complete, she chose to wait until she crossed the final hurdles before starting work this time, picking up side jobs in the meantime.

Roughly three months later, Guerrero began working as a substitute teacher at the school—a different position altogether. That meant she had to undergo the entire application process all over again, including the mandatory tuberculosis tests, after hiring for the reading specialist gig moved too slowly once again.

Her first day on the job was in late April, mere weeks before the end of the school year.

‘A Perfect Storm of Issues’

San Francisco Unified School District, like other school districts, is in dire need of passionate, dedicated teachers like Guerrero. Of an estimated 500 classroom vacancies expected for the 2023-24 school year, only 278 have been filled as of Thursday.

While district spokesperson Laura Dudnick maintains that this is consistent with recent years (opens in new tab), its head of human resources Sam Bass told The Standard in July 2022 that the district saw teachers “resign in record numbers.” Around this time last year, 450 classroom positions needed filing.

The teachers’ union expects more positions will open now that the school year is over. The school district did not reach labor agreements in time for approval (opens in new tab) before summer break, which may push some uncertain educators to leave while the district has less of a competitive edge in recruiting new staff.

“Amid a nationwide teacher shortage, we have successfully hired hundreds of new educators for next school year in recent months,” Dudnick said in an email. “We routinely examine our practices for opportunities to improve the onboarding experience for candidates and for new employees.”

An independent 2009 study by education consultants (opens in new tab) found that, despite successful recruitment efforts, the district loses strong applicants because of late hiring due to a variety of factors. Most applications were received in the spring, but over a third of new hires did not receive an offer until August, weeks before the start of a new school year. The study also found that the district could increase retention by improving HR practices, which is perhaps still relevant 14 years later.

Guerrero’s rough entry to the district is “spot on” in capturing the experiences of new teachers, said union leader Cassondra Curiel. A payroll system that stiffs teachers and a central office undergoing a cultural transformation under a relatively new superintendent only exacerbated the issue, she said.

“That’s an accurate picture of what it’s like right now to be onboarded as an educator right now in this district,” said Curiel, president of the United Educators of San Francisco. “It’s a perfect storm of issues that can only be overcome by continuing to go through it. I hope this was the messier part.”

Despite the deeply emotional and “dehumanizing” experience with the district, Guerrero still plans to teach there.

“I don’t think this district has learned yet,” Guerrero said. “A lot of teachers now are realizing that enough is enough. There’s so many vacancies—that’s saying something.”

This fall, Guerrero begins a master’s program in urban education and social justice at the University of San Francisco, intending to work as a paraeducator in the district in the meantime. The first-generation college student also plans to pursue a doctorate, eventually becoming a professor.

“Now that I know the beast that this system is, I’m no longer scared,” she said. “I think I earned my stripes.”