It’s been one month since San Francisco launched a multimillion-dollar legal apparatus to help mentally ill people receive care, and so far, eight people have been referred to the program.

San Francisco is one of seven cities tasked with leading the implementation of a new legal system, championed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, called Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment Court, or CARE Court, which is supposed to assign and administrate a treatment plan for people who suffer from severe mental illness.

San Francisco received $4.3 million to implement the court, and the city’s Department of Public Health estimated in April that up to 2,000 people would be eligible for the court annually.

As of Thursday afternoon, the court received eight referrals in total since launching Oct. 2. But it’s unclear how many of those people are eligible for the program since the intake process takes months, according to Melanie Kushnir-Pappalardo, director of the city’s collaborative court system.

Kushnir-Pappalardo said she considers the court’s slow start a rare blessing in the world of mental health treatment, where clients usually greatly outnumber staff.

She said the program’s stringent requirements (opens in new tab), which only allow people with schizophrenia or other debilitating psychotic disorders to participate, have likely deterred many people from submitting referrals.

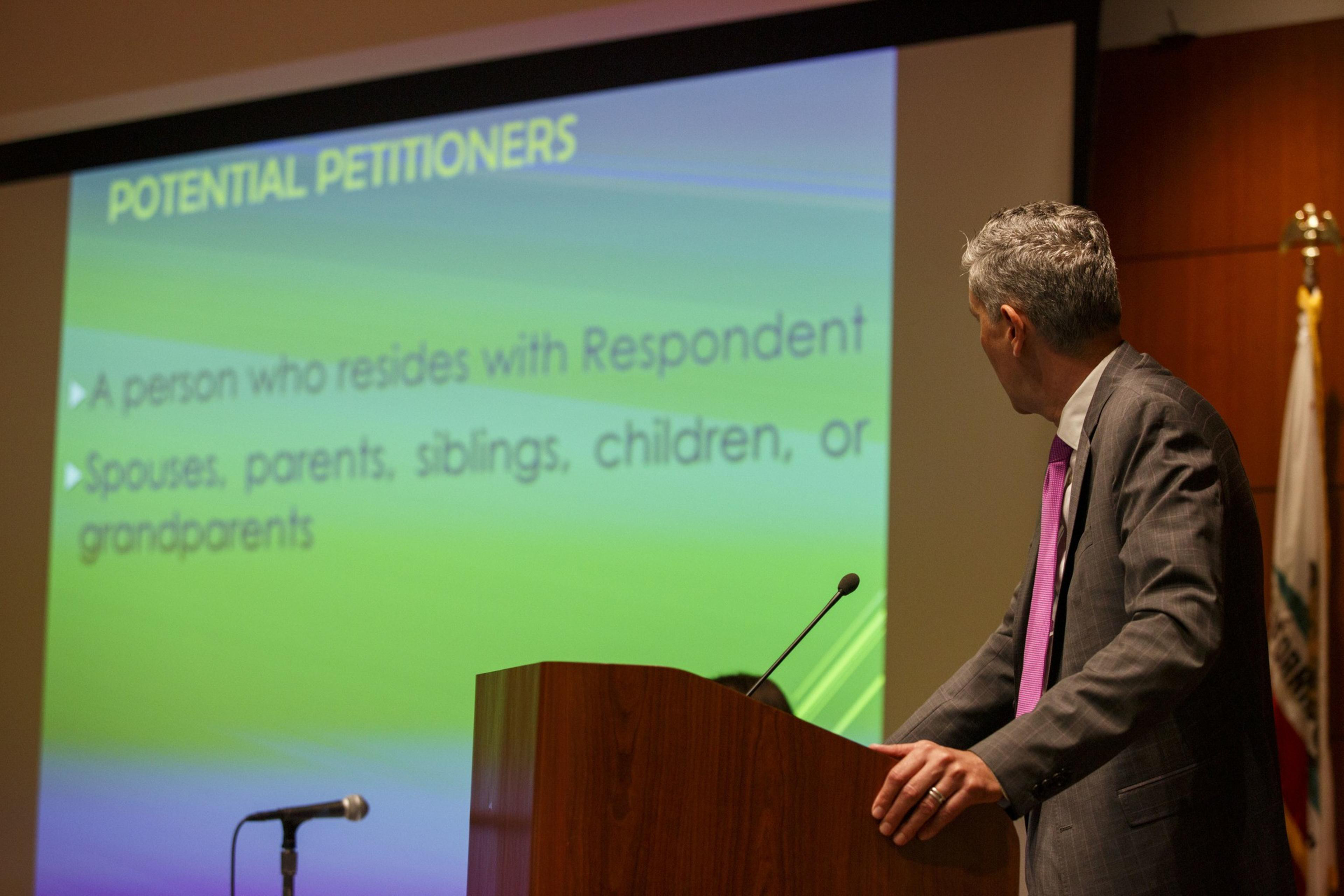

Family members, roommates, outreach workers and medical professionals can refer people to the program by filing a petition form. Once enrolled, participants are assigned a team tasked with helping them navigate a treatment plan.

“It can’t help everybody; it’s not meant to help everybody,” Kushnir-Pappalardo said. “The positive is that it’s truly truly focusing on some of our most seriously mentally ill San Franciscans.”

Even before the court’s implementation, critics questioned how the program would fare as cities across the state face a shortage of nationwide behavioral health workers and treatment beds.

“Maybe it’s a good thing that the system’s not overwhelmed so that individual cases can get appropriate attention,” said Tal Klement, deputy director of the Public Defender’s Office mental health unit.

Kushnir-Pappalardo said San Francisco’s pace of CARE Court referrals appeared to be on track with other counties across the state.

CARE Court was proposed as an alternative to conservatorship, the most intensive form of mental health care in which a person is assigned a guardian to handle their affairs. The program is intended to allow people to enter treatment before they require such intensive care.

But cities stand to be monetarily penalized for every person who falls out of compliance with their treatment plan, and those who don’t follow through may be eligible for conservatorship.

Meanwhile, treatment beds for conserved individuals are already out of space.

The California Department of State Hospitals estimated in October last year that its intensive care facilities for conserved people were 99 patients over capacity. The San Francisco Department of Public Health has also acknowledged that its long-term treatment beds are usually filled.

Those involved in running CARE Court said they were unable to comment on the progress of people participating due to medical privacy laws.

Kushnir-Pappalardo said one of the most challenging aspects of the court will be convincing participants to engage with the program.

“These are folks who aren’t doing great in the community. … They haven’t wanted to engage in services; they’re not necessarily easy to find and locate,” Kushnir-Pappalardo said. “It’s not going to be a fast process.”