San Francisco surfers are not stoked about a city plan to transform part of the Outer Sunset’s Great Highway, fearing it may ruin some of Ocean Beach’s world-famous waves.

The Outer Sunset neighborhood bordering Ocean Beach is a hub for surfers who dare to paddle out to the city’s ever-tempestuous, frigid and shark-filled waters, which can produce waves that tower over 20 feet in the winter. Several surf shops and a newly renovated Pitt’s Pub, a surfer-owned dive bar, call the “Outerlands” home.

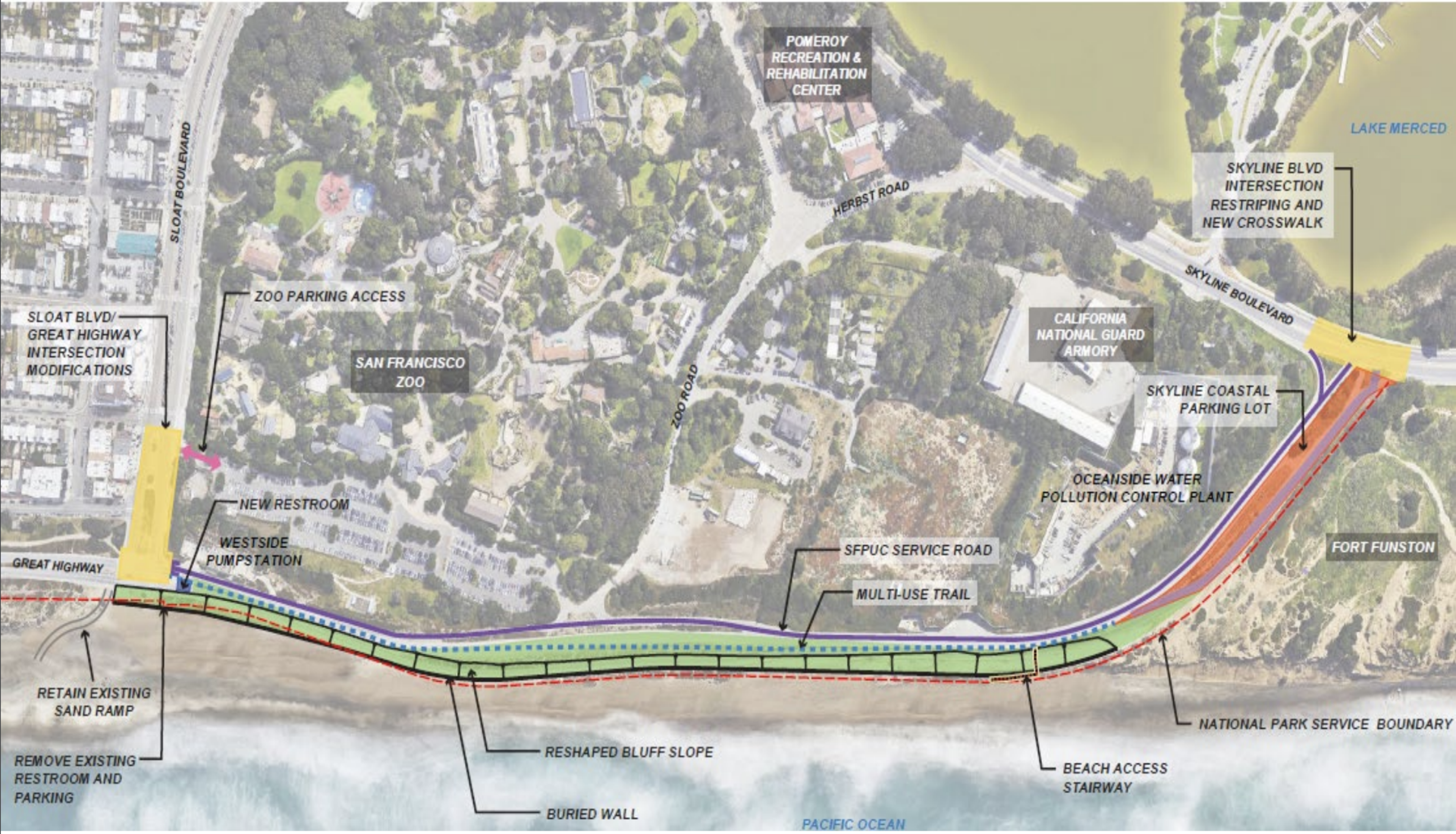

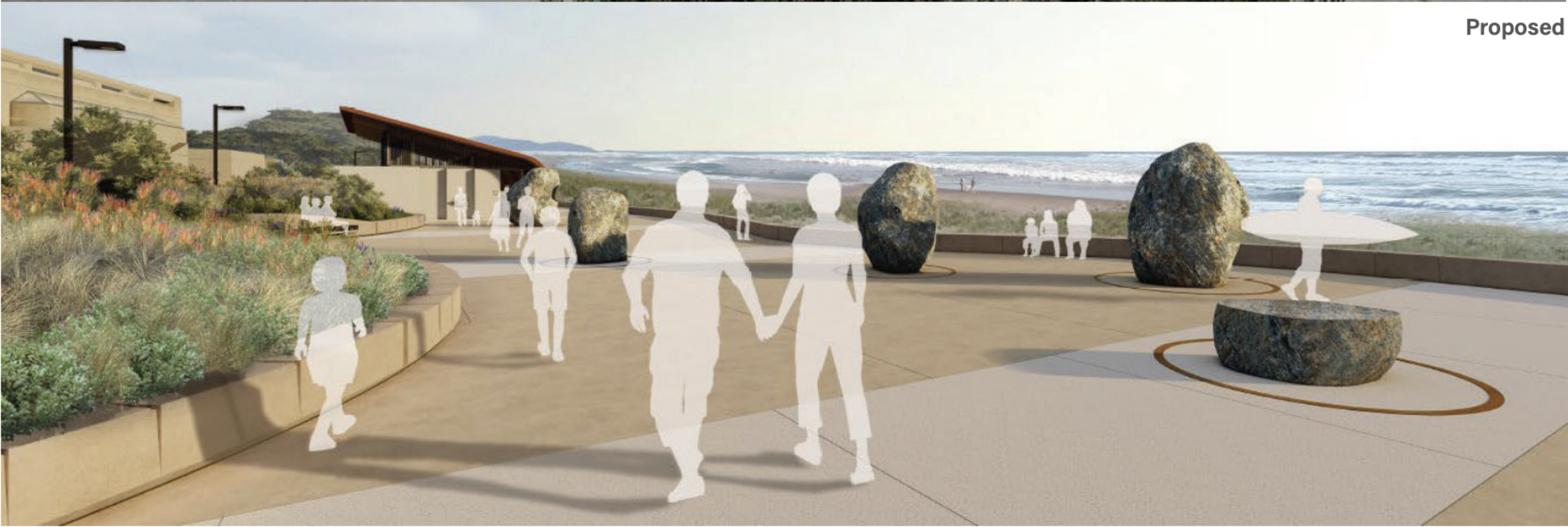

But tucked into an approved plan to bring bike lanes, an art exhibit and a beach access ramp to the beach’s southern end is a proposal to construct a 3,200-foot underground wall.

The wall, designed to protect the nearby wastewater plant from coastal erosion, could ruin some of the beach’s waves by displacing sand, according to experts and surfers. The plan will also permanently close the Great Highway to cars between Sloat and Skyline boulevards, but it differs from a ballot measure to close the highway between Sloat Boulevard and Lincoln Way.

This area of the beach near Sloat is where some of San Francisco’s first surfers ventured into the dangerous waters, according to Matt Lopez, co-owner of Pitt’s Pub and lifelong Ocean Beach surfer. He said the Sloat surf break has already gotten worse in recent years as the city routinely dumps sand to slow erosion; he fears more drastic changes could ruin the spot forever.

“Sloat was the birthplace of surfing at Ocean Beach,” Lopez said. “If you ruin the waves, in a way, you’re kind of ruining the neighborhood. I’m not living on the Great Highway for the weather.”

OB surfers are so salty about the plan; some say they’ll leave the city if the waves disappear or change for the worse.

During the winter months, the beach’s waves have graced the pages of international surf magazines and attracted some of the best athletes in the sport. In 2011, the greatest competitive surfer of all time, Kelly Slater, won his final world title (opens in new tab) at the beach.

“Surfing, like skateboarding in SF, is one of the last cultural staples that hasn’t been completely overrun by gentrification,” said Joe Dolce, a 19-year-old San Francisco native and Aqua Surf Shop staffer.

When asked if he could imagine Ocean Beach without surfable waves, Dolce just looked downward and shook his head in disgust.

The Surfrider Foundation contends the city is merely prolonging the inevitable relocation of its wastewater plant. They argue that construction of the underground wall, known as shoreline armoring, would displace sand and cause the south end of the beach to disappear altogether.

“The wastewater plant is going to have to move eventually,” said Laura Walsh, Surfrider’s California policy manager. “It’s just going to get more and more expensive.”

However, the city argues the underground wall would protect vital infrastructure from powerfully encroaching swells. Land is scarce in San Francisco and relocating the wastewater facility is a huge undertaking.

“San Francisco’s residents living on the west side depend on the Oceanside Treatment Plant every day for sanitation and to protect public health,” Nancy Hayden Crowley, press secretary at the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, said in a statement.

Crowley argued the renovations would create “a wider beach more resilient to erosion” and said the city plans to “monitor and replace sand as needed.”

Mayor London Breed approved the plans on April 24, but they still require authorization from the California Coastal Commission, which said it won’t approve the plan in its current form. On June 10, the city requested a six-month extension to alter its $250 million plan.

The Sierra Club and Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who is running for mayor, were among those who submitted letters opposing the wall’s construction.

Bob Battalio, a semi-retired engineer who contributed to the Ocean Beach Master Plan to combat sea level rise, said it’s possible the wall could negatively impact waves at the southern end of the beach. However, he said the impact would likely be isolated to the inside sand bars, leaving outside waves unaffected.

Still, he agreed the city should consider modifying or relocating the wastewater plant in the future.

“I think the concerns that Surfrider has are valid,” Battalio said. “We should perhaps have a longer-term perspective.”

A study from a UC Santa Cruz professor Gary Griggs, a coastal zone researcher, shows (opens in new tab) such anti-erosion walls have displaced sand and reduced the size of beaches.

‘It would be a tragedy’

Grant Washburn, a longtime Ocean Beach surfer who’s spent decades tracking Northern California’s ocean swells, urged caution in moving forward with construction that could negatively impact the waves, and thus the city’s surf community.

“It would be a tragedy,” Washburn said. “I think some people don’t realize that it’s such a special place.”

Ocean Beach surfers say they’re used to the beach’s constantly changing conditions, which can vary block by block and hour by hour due to shifting sand and violent currents. But still, Lopez said he is fed up with the city’s policies in the Sunset—such as the closure of the Great Highway on weekends and during the pandemic—which he believes overlook the needs of surfers and working-class people with cars.

As a surfer, a business owner, and a soon-to-be father, Lopez said he needs his car to transport products, his family and his surfboards. He explained that the freedom to choose whether to own a car is part of what makes the Sunset different from the rest of the city.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen, maybe it makes the best wave San Francisco has ever seen,” Lopez said. “But they’re killing the culture of what made the Sunset a community before anyone cared about it.”