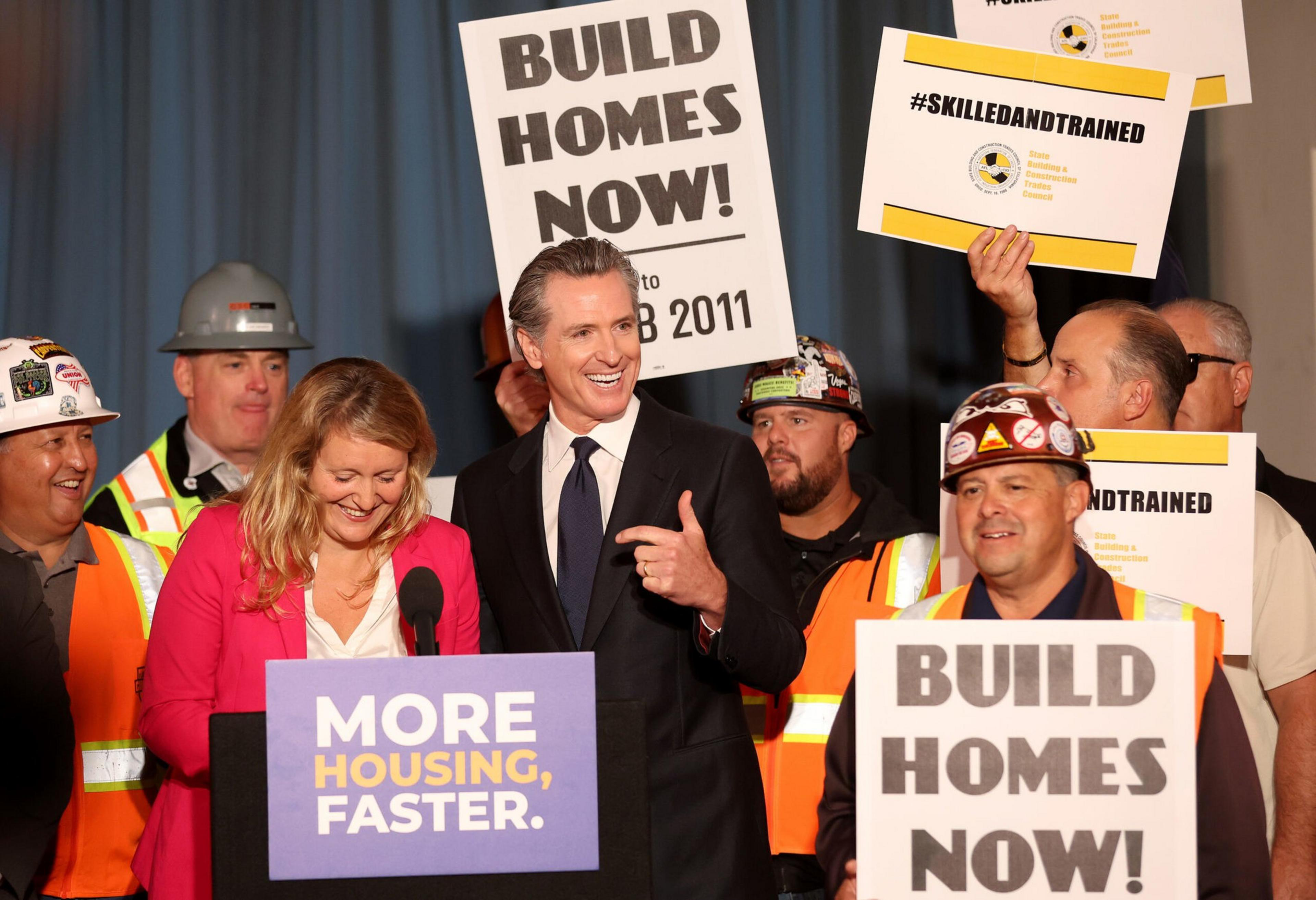

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Monday signed two housing reform bills to speed up development in California a week after fierce opposition from environmentalists and labor groups nearly tanked the legislation.

The housing measures were folded into the $321 billion state budget last week after Newsom said he would not sign the spending plan without the changes, which proponents say will make it easier to build new homes and infrastructure in some cases by circumventing the California Environmental Quality Act.

The bills will allow developers to bypass the law’s more rigorous environmental review process for certain housing projects in urban areas and will streamline the construction of new infrastructure ranging from clean water projects to health clinics.

“This is…the most consequential housing reform that we’ve seen in modern history in the state of California,” Newsom said Monday night before signing the bills (opens in new tab).

Newsom said the changes would end the “abuses of the CEQA process” that have beleaguered cities for decades and help advance the “abundance” movement in California.

The measures, Assembly and Senate Bills 130 (opens in new tab) and 131 (opens in new tab), still fall short of what many pro-housing and abundance advocates had hoped would be a total overhaul of CEQA.

That 1970 law was designed to safeguard residents against environmental harms, but critics often portray it as an overused tool to delay or block much-needed development.

Each of the two bills hit its own roadblock last week, sending lawmakers scrambling to meet a Friday deadline to send the budget to Newsom before the fiscal year starts Tuesday.

In the Assembly, opposition erupted after Assemblymember Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) added minimum-wage requirements to her bill, which eases restrictions on housing in cities and other developed areas.

That change set off a political brawl between already warring construction unions (opens in new tab), with one side arguing that the minimum-wage rules would protect workers and the other adamant that they would unleash rampant exploitation at job sites.

The feud left Democrats panicking over which side to take. Wicks decided not to include most of the wage requirements in the final version of the bill, easing its path to Newsom’s desk while leaving the major housing changes intact.

“It is too damn hard to build housing and all the other things that we care about,” Wicks said. “We told the world we are ready to be open for business — the business of building housing.”

The Senate bill (opens in new tab), which focuses on infrastructure projects, hit similar resistance from a coalition of environmental groups that see CEQA as an important protection against rampant development.

State Sen. Scott Wiener’s (D-San Francisco) initial version of the bill would have tackled some of the most controversial elements of CEQA by making it much harder for opponents of projects to file lawsuits.

CEQA lawsuits can add significant costs and several years to a project’s timeline, a hurdle that makes it nearly impossible for California to add the millions of new homes it needs, critics say.

“It’s not just projects that get blocked,” said Matthew Lewis, communications director for the pro-housing group California YIMBY. “It’s all the projects that never get proposed, because the proponents don’t have legal teams that they can fund and prepare to take on a CEQA challenge.”

Housing advocates — their confidence buoyed by the abundance movement (opens in new tab) popularized by journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson — saw Wiener’s bill as a chance to kneecap CEQA’s power and pave the way for more housing and infrastructure in California.

Instead, a coalition of environmentalists, backed by sympathetic Senate Democrats, opposed the scope of the bill, and spent much of last week successfully negotiating for incremental changes to CEQA.

They argued the broad overhaul would “poison our air, water, and land across the state,” often pointing to a June poll of 600 likely voters that showed 75% supported CEQA (opens in new tab), and 66% opposed changing the law as a way to allow developers to build housing.

“This half-baked policy written behind closed doors will have destructive consequences for environmental justice communities and endangered species across California,” Jakob Evans, senior policy strategist with Sierra Club California, said in a statement. “It is extremely disappointing that California’s leadership is taking notes from the federal administration by ramming through this deregulation via the budget process.”

The bills still include some limits on CEQA lawsuits. But the major differences now add a variety of CEQA exemptions for infrastructure projects such as clean water and broadband, child-care centers, food banks, and health clinics, among others that meet certain criteria.

The bill also allows projects that narrowly miss a CEQA exemption to fast-track development by focusing the environmental review process more specifically on the disqualifying factors. And it aims to make it easier for cities such as San Francisco that have submitted state-approved housing plans to meet those goals by shielding them from duplicative CEQA reviews.

UC Davis law professor Chris Elmendorf said, taken together, the two bills could make it far easier to build housing in a state that needs millions more units.

But, he added, CEQA is only “one piece” of the problem. Restrictive zoning rules, high development fees, and other requirements “will continue to be significant barriers” to construction even with the changes Newsom signed into law.

Even so, the new laws ignited a wave of celebrations among YIMBY advocates in California.

“It is so critically important for California to show that we can get things done, to make people’s lives better and more affordable,” Wiener said. “And that’s what these bills are about.”