Want the latest Bay Area sports news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here to receive regular email newsletters, including “The Dime.”

CC Sabathia’s journey from a challenging section of Vallejo to baseball Hall of Famer will culminate Sunday, when he’s inducted in Cooperstown, N.Y.

“I can’t wait to celebrate,” Sabathia said, “and a lot of my speech is about the village that raised me from Vallejo.”

The 45-year-old lefty continues to embrace the time he spent playing in Cleveland and the Bronx, sandwiched around a quick stop in Milwaukee. He said he might not have been Hall-bound without the training and tutelage he received early in his career in Cleveland, where he won the 2007 Cy Young Award. Upon joining the Yankees, he found a permanent home for his family in Alpine, N.J., then won a 2009 World Series ring with New York.

Raised an A’s fan, Sabathia envisioned being a big-leaguer in the Bay Area and had a feeling he’d be drafted by the Giants when they had two first-round picks in 1998, but they used the first on Tony Torcato of Woodland. Before their next pick, Cleveland nabbed Sabathia.

Section 415: Min Woo Lee, Steph Curry, and the story of The Bay Golf Club

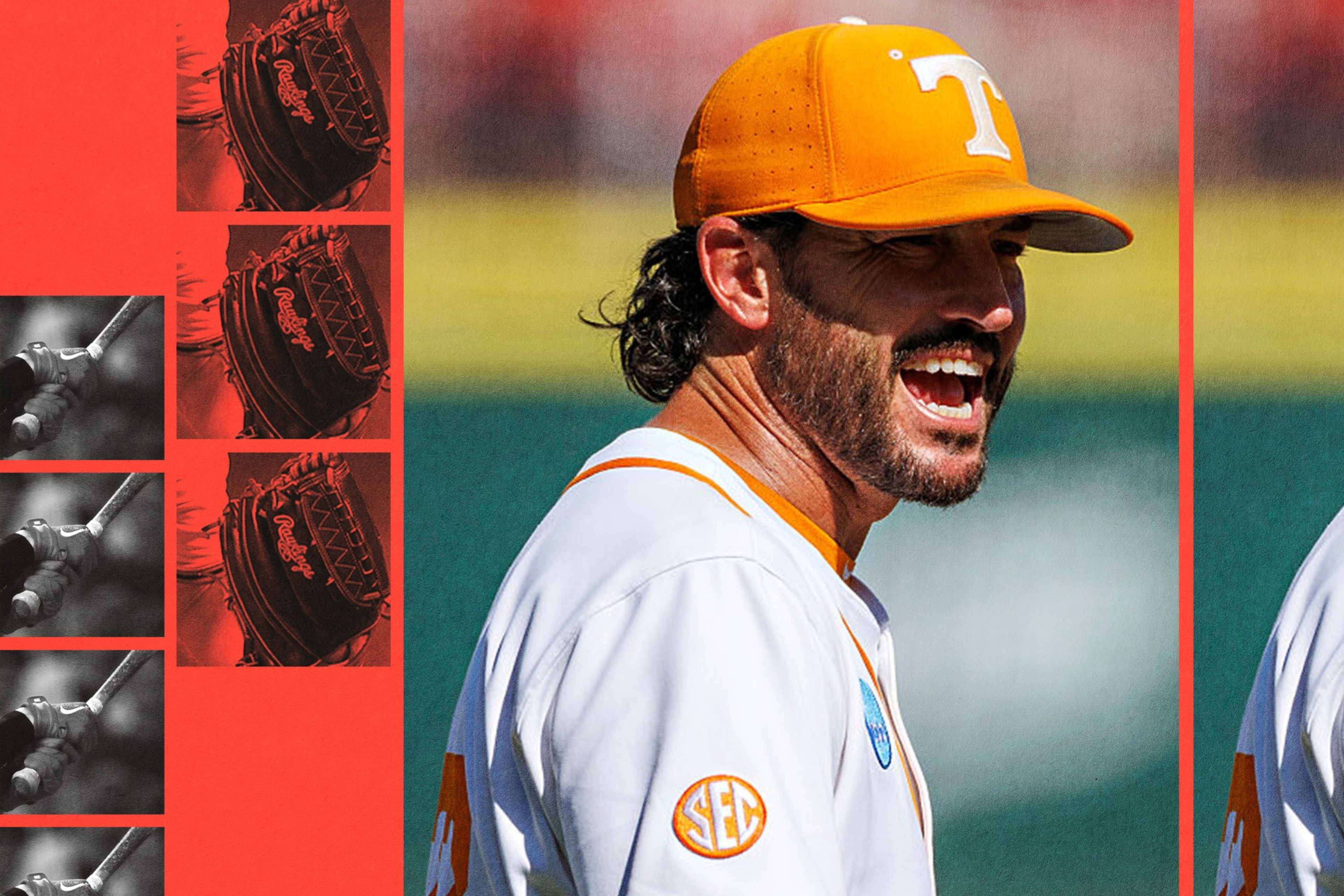

Section 415: The Giants’ hire of Tony Vitello marks the start of a bold new era

Section 415: Ballers manager Aaron Miles on bringing a title back to Oakland

The Giants had another opportunity in free agency before the 2009 season and made a strong pitch — imagine a rotation of Tim Lincecum, Matt Cain, Madison Bumgarner … and Sabathia — but Yankees GM Brian Cashman was prompted to add a seventh year to his offer and secure the deal.

I asked Sabathia last week about his 19-year career and whether he ever thought about how his life would be different had he pitched so close to Vallejo, reminding him that the Giants went on to win three World Series titles while the Yankees won one.

“Me being so connected to that city, it’s good that I played on the East Coast. It’s good that I was a six-hour flight away,” he said. “I think had I been that close, my career probably would’ve turned out a little different. So, yeah, I mean, obviously, you watch what the Giants did, and I grew up a big A’s fan and went to a lot of Giants games too. But no, I think it played out the way it should have.

“This was the best decision I could have made, and I still live here and am part of this community. I think my career ends up different if I get drafted by the Giants and I’m around Vallejo all the time.”

For many big-leaguers, playing for a hometown team can be a challenge, with the pressures of constantly catering to friends and family. Sabathia would have faced additional pressures, having grown up in the Vallejo neighborhood of Country Club Crest — aka the Crest — where drugs, crime, and other dangers were commonplace.

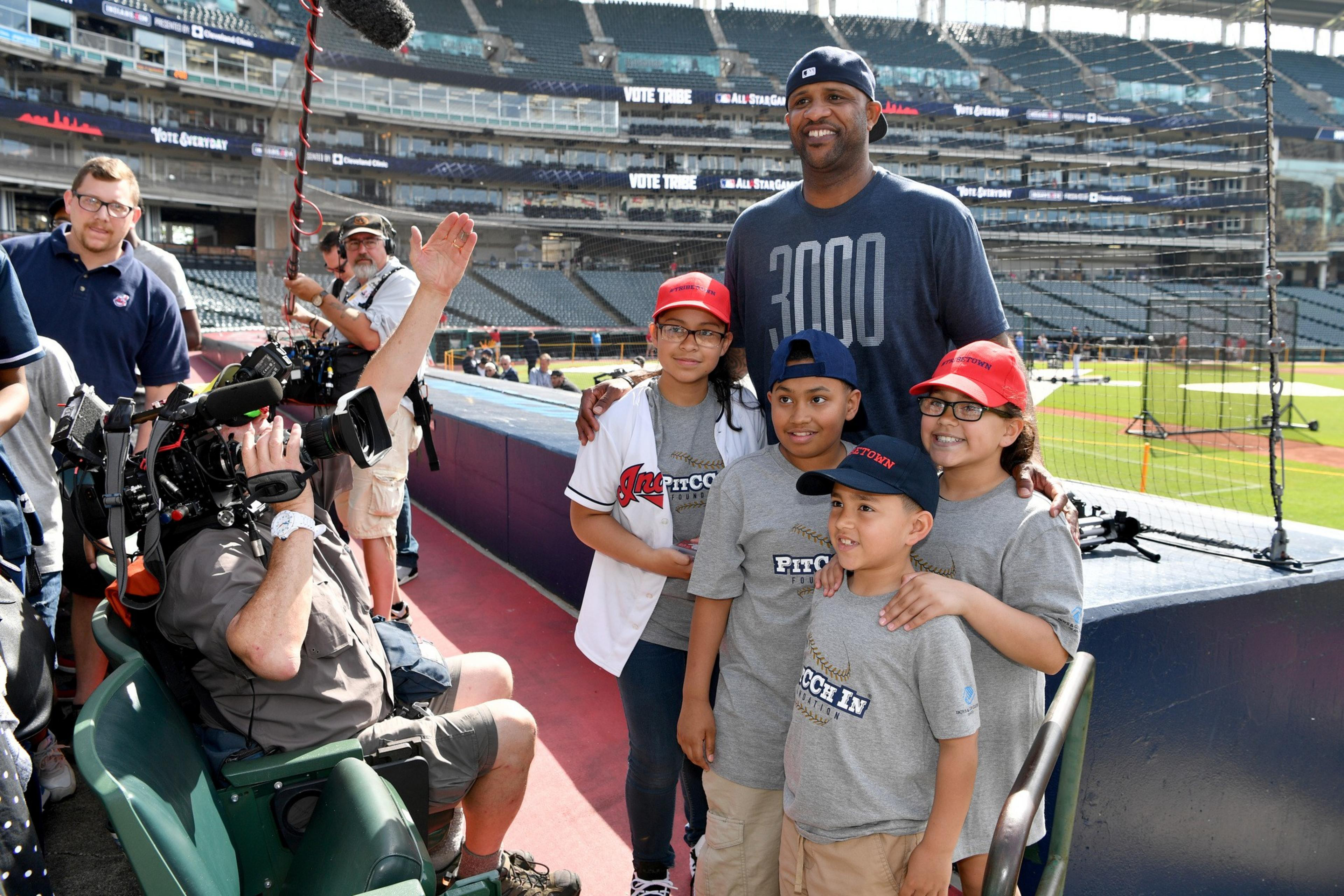

Through it all, Sabathia never forgot his roots and continues to give back to Vallejo through his PitCCh In Foundation. In his fabulous 2020 documentary (opens in new tab), he speaks of learning to pitch by throwing grapefruits in his grandmother’s backyard and details his parents’ separation, his father’s absence and struggles with HIV until his death in 2003, and his own bout with alcoholism.

If there were a young CC in Vallejo nowadays, facing similar hardships, would it be easier or tougher to follow a similar path to the big leagues?

“I think it’d be way tougher,” he said. “I think just the situation that I was in, with me and my mom and after my dad left, and then my grandmother. Obviously me playing three sports would have hurt me in this day and age. And not having the money to be able to get to LakePoint in Atlanta [where kids get opportunities to play in front of pro scouts and college coaches] and all these different showcases.

“Somebody would have had to come out and scouted me in Vallejo, or I would have had to find a way to get on one of these teams, somebody paying for me to get to one of these tournaments. So it would have been incredibly hard in this day and age for somebody like me, the way I came up, to make it. For sure.”

It’s no wonder that Black players occupied just 6.2% of opening-day roster spots, a drastic drop from decades past. MLB has several initiatives in place to bring Black kids, including those from the inner cities, into the game; for example, the MLB Develops program.

There’s also the Players Alliance, a nonprofit organization created by Sabathia and other former players to make the game more equitable and accessible. So the next CC could have a chance.

“That’s why we started the Players Alliance, and that’s why we’re doing the things that we can and trying to ID these kids in these focus cities, to get that kid that’s been lost,” said Sabathia, who works in the commissioner’s office. “Kids are playing at a high clip, and they’re really, really good. We just need to find a way to get them seen and get them on teams where they can get scouted.”

A first-ballot Hall of Famer, Sabathia struck out 3,093 batters and won 251 games, and his 21-win season in 2010 earned him membership to the Black Aces, the group of Black players with 20-win seasons. Mudcat Grant, who finished his career with the 1971 A’s, coined the term in his 2007 book, and Sabathia is proud to be in the company of one of his idols, four-time 20-game winner Dave Stewart.

He’s the third member of the Black Aces to reach the Hall of Fame, following Bob Gibson and Ferguson Jenkins. Sabathia has become close with Jenkins, who called the incoming Hall of Famer to welcome him to Cooperstown.

“The one thing that keeps crossing my mind is who’s next?” Sabathia said. “Through the Players Alliance and some of the efforts that we’re putting together for this next generation, I almost feel even more responsible now to be on guys about being that next Black Ace, whether it’s Taj Bradley or now Chase Burns or Hunter Greene, or whoever else.

“I don’t want to be the last Black pitcher to win 20 games and be in the Hall of Fame and all these things. I’m excited and incredibly honored and humbled that I am, but now it’s got me on the search of who’s next and what can I do to get that person or that kid on the mound and in the right direction as a starting pitcher.”

At Sunday’s induction, Sabathia will join Ichiro Suzuki — who beat him out for the Rookie of the Year Award in 2001 — and Billy Wagner. Dave Parker and Dick Allen will be inducted posthumously. Sabathia grew up with the late 1980s A’s and loved Parker’s game, especially because Parker was a dominant presence at 6-foot-5. (Sabathia grew to 6-foot-6.) “One of my favorite players,” he said.

In the final days before the induction, Sabathia is preparing for his big moment and fine-tuning his speech, which will touch on his inspirations in Vallejo, including family, friends, and a laundry list of athletes he admires.

“I think about my father every single day and the relationship that he would have with my boys and how excited he would be living here in New York and going to Yankee games. He was such a huge Yankee fan too,” Sabathia said. “So many different people from Vallejo are coming out. That city is super special. I always tell people that I didn’t have to look much farther outside of that city for inspiration. There was so much talent in that town that I didn’t have to look very far.”