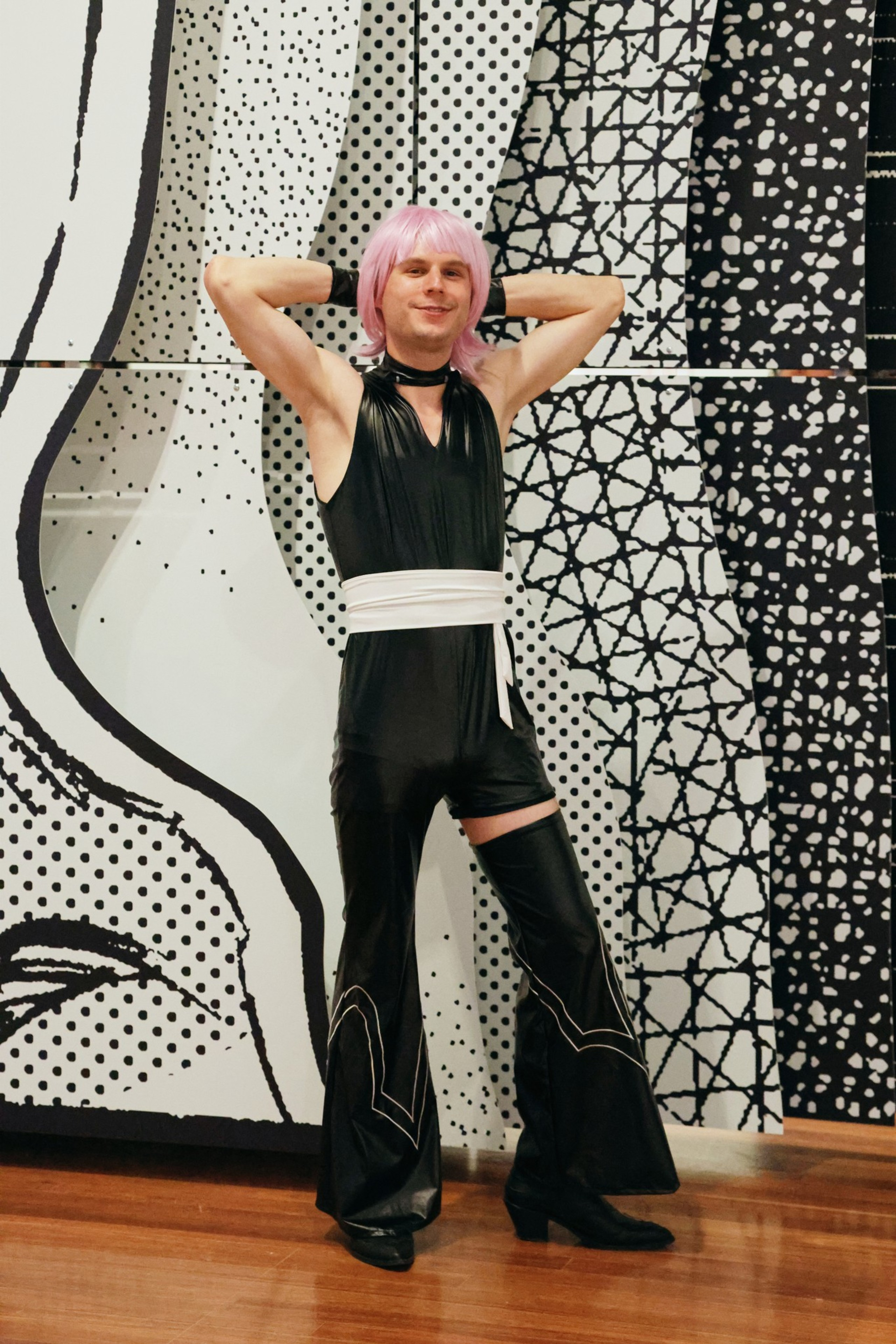

Jyke Telmo and Sam Bell crossed the Bay from Alameda to Golden Gate Park on Saturday morning, striding into the de Young Museum in full cosplay as Jotaro Kujo and Noriaki Kakyoin from their favorite manga, “JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure.” The arrival set the tone for a show where fans are not just spectators but part of the spectacle.

“I really believe that manga is an art, and it’s always been an art — even though my family will say otherwise,” Telmo said.

“Art of Manga,” on display at the de Young, is one of the first large-scale exhibitions of its type in the U.S. The exhibition opened Saturday, with fans from across the Bay Area flocking to the basement gallery, dressed head-to-toe as their favorite characters.

At the entrance, the mood is more Pop Mart than museum, with dozens of Japanese vending machines. Inside the gallery, the exhibition tells the story of a dynamic global art form, traced through a timeline of styles and era-defining artists.

The gallery walls have been transformed with sketches, comic-strips, murals, and digital art. The show assembles more than 600 original drawings — many being displayed outside Japan for the first time. Visitors trace the medium’s evolution from early postwar creators through today’s digital platforms.

“Art of Manga” highlights the defining artists and milestones of a genre that spans humor, romance, absurdism, and queer narratives wrapped in psychedelic, if occasionally over-busy, design.

For Telmo, who started reading manga at 10, seeing such a range on view in San Francisco felt both validating and overdue.

“I really recommend Rumiko Takahashi — she’s the godmother of that genre of shojo anime and manga,” he said. “This exhibit has queer, LGBTQ manga. They have such a big emphasis on that. It’s wonderful that, because we’re in a city that is very open, we can have these kinds of attractions, too.”

That inclusivity is reflected in works like Tagame Gengoroh’s homoerotic stories, which helped push mainstream Japanese comics toward greater LGBTQ representation, and in Yamashita Kazumi’s painterly, oil-like pages that soften the rigidity of neighboring artists.

The show is also a behind-the-scenes education. Okamoto “Kinpachi” Masashi, curator of the “ONE PIECE ONLY: How Manga Is Made” section, said he wanted visitors to understand the production side of manga.

“Nowadays, many people read “One Piece” on their smartphones,” he noted. “But they don’t know how they are made in the factory with printing plates. We want to keep and archive them. With this exhibit, we can show people how the printing machine works and how it is made.”

For fans like Kelsey Malinzak, who began reading Inuyasha at age 10, the experience is personal and almost nostalgic. “This was a real full-circle moment,” she said.

“Being an adult, living in the city now, seeing the original prints of these things that I fantasized over and got lost in as a kid — it’s pretty mesmerizing.”