Lei Huang is not the typical renter in his Chinatown apartment complex, where most tenants qualify as low-income.

A Microsoft data scientist specializing in artificial intelligence, Huang moved into his Waverly Place apartment in February for what was meant to be a two-month social experiment — a way to immerse himself in the neighborhood by living in the “single-room-occupancy” hotel.

Eight months later, however, his experiment has turned into something far deeper, a lifestyle that Huang says has given him a stronger connection to his fellow Chinese immigrants and their stories.

“I’ve gained so much more than I expected,” Huang, 40, said in an October interview, speaking in Mandarin.

The Standard has followed Huang for the last nine months, tracking his move from a stately, four-bedroom house in Eureka Valley earlier this year to the tiny, 120-square-foot room at the SRO, which he’s renting for $1,000 a month. The building, like other SROs, predominantly shelters San Francisco’s low-wage and immigrant families.

Huang was able to apply for residency at the privately owned SRO, and was not asked to go through a low-income background check more typical of nonprofit-run facilities.

While rent at SROs is far cheaper than the $3,000-plus price tenants currently shell out for an average one-bedroom place in San Francisco, the affordability comes at a cost to privacy — and without the usual amenities. Residents share bathrooms, kitchens, and narrow hallways, while individual rooms are often no bigger than a parking spot.

About 30 people live in Huang’s building, which is owned by the historic Ning Yung Family Association. Each floor has 13 units, with 15 tenants sharing three toilets, two showers, and four sinks.

But Huang has found ways to make his otherwise shabby space comfortable. Sunlight often streams through his window, which overlooks Chinatown’s dense streets and downtown’s skyscrapers. His floor is covered in a red-and-green floral carpet, and he’s decorated the room with a small two-seat sofa and a standing desk.

“I feel like I’ve truly blended in with the residents here,” he said. “These interactions are meaningful to me, something I genuinely enjoy.”

‘A more authentic experience’

Born in Hubei to two college teachers, Huang emigrated to the U.S. in 2008, and in 2023 moved to San Francisco. With a degree in biology and statistics from an elite university in Southern China and a Ph.D. in computational biology from Cornell, Huang’s background, combined with his compensation package of more than $200,000 from Microsoft, means he could easily afford a luxury apartment anywhere in the city.

His spacious Eureka Valley home served as an informal hub for Huang and his friends, who would gather for quiet meditation sessions and conversations about spirituality. They shared meals, lingered late into the night, and found calm in an otherwise busy city.

Huang’s inspiration for moving to an SRO began with his time volunteering as a Chinatown tour guide in 2024. On his walking tours, Huang often pointed out SRO buildings to tourists and noted their importance to Chinese immigrants, whose stories, cuisine, and culture he credits with making the neighborhood so vibrant. Over time, he started to feel uneasy about narrating others’ lives from a distance.

With no website listing SRO vacancies, Huang relied on Chinatown connections to find out about open apartments. That’s how he learned a room was available in the century-old Ning Yung building, a private SRO, and decided to apply.

He was expecting to stay just a few months — long enough to get a feel for what it was like to live in an SRO without making a long-term commitment. “I wanted a more authentic experience,” he said. “I felt like I needed to live it to really tell the story.”

Huang knows how unusual — and perhaps controversial — it might be for someone like him to voluntarily live in an SRO, given the short supply of affordable housing in San Francisco.

Even with San Francisco’s limited stock, however, vacancy rates in Chinatown’s SROs are currently higher than before the pandemic. Malcolm Yeung, head of the Chinatown Community Development Center, an operator of many SRO buildings, said current vacancy rates for nonprofit-operated facilities exceed 5%, while the rates in privately owned SROs are likely higher.

Private SROs often have a more flexible screening process for applicants like Huang, according to Yeung. But for nonprofit-operated SROs, where rooms are reserved for low-income tenants, someone like Huang would likely not qualify, he said.

In 2023, The Standard published an investigation into cramped living conditions (opens in new tab) at the housing facilities. The city soon started to aggressively relocate large families that had crowded into SRO units.

In January, days before his move, Huang admitted in an interview that he was flooded with emotions and feeling nervous at what was to come.

“It’s going to be an adventure. I want to really get integrated and more connected with this neighborhood,” he said at the time. “But like any big transition, there’s excitement, anticipation — and also anxiety.”

Living, gossiping in SROs

Most of Huang’s new neighbors were elderly immigrants or low-income families. At first, it was hard to connect with them and find that neighborly vibe he craved at the start of his journey.

But little by little — by helping fix their Wi-Fi, giving people rides to Costco or the airport in his Tesla, and joining kids’ birthday parties — he became part of their world. “I’m one of the few younger people here who can help them, who can share some youthful energy,” Huang added.

Through small moments, like reading aloud letters or teaching them how to use their phones, he made intimate connections with fellow immigrants he otherwise never would have met.

“They mean a lot to me, and I think I mean something to them, too,” he said in October.

Despite his new relationships, there were less pleasant parts of the SRO experience, Huang admitted. The communal areas could be filthy, and on busy mornings, he sometimes had to wait in line to use the toilet or sink. Conditions were even more frustrating at night, when he needed to use the bathroom and had to walk across the hallway in the dark.

Even with some downsides, Huang, a self-claimed “minimalist,” said he found his SRO living easier than the families with small children who must crowd into a single room. He has also found ways to make his experience more comfortable: His tech job comes with company-provided meals, so he doesn’t need to compete for the kitchen space. And he pays for a laundromat to avoid the daily scramble for clotheslines in the hallway and on the roof.

His new friends haven’t held any of those advantages against him. Janne Wang, a tenant who also serves as the building’s manager, said that most other residents speak only Mandarin, Toishanese, or Cantonese and little English, so they often turn to Huang for help. She shared a story about Huang helping organize a birthday party in March for her 10-year-old daughter, and said he sometimes drives her around town for errands.

Wang acknowledged how unusual it was for Huang, with his big tech salary, to live in an SRO. But she said she understands his motivation. “I guess he just wants to experience life,” Wang said in Cantonese.

Ding Lee, head of the Ning Yung Association and Huang’s landlord, also said he stands out as a tenant. “It’s rare for someone to have his mindset and actions,” Lee said in Cantonese. “He truly understands SRO residents’ lives, breathes the same air, and shares their fate.”

Huang knew he was fully integrated into the community when he started picking up on some of the more complex — yet subtle — social dynamics between different tenants.

In Chinatown, Huang learned, gossip can be a critical bonding tool. He realized he was no longer just a guest in the building when neighbors began confiding in him about their friends and foes: who liked whom, who didn’t get along, who held grudges, and who shared frequent meals.

On a Friday in mid-October, a grandmother in the building greeted Huang with a cheerful “good morning.” Moments later, a middle-aged woman said hello too, then pivoted to airing her grievances about the grandmother.

“In such a small building, you wouldn’t expect so many layers,” Huang said. “But there are cliques, tensions, little alliances. It’s fascinating.”

Chinatown becomes home

Living in an SRO has changed how Huang views the buildings and the stereotypical “substandard, inhumane conditions” that he initially thought festered in the spaces. With time, he’s come to understand the rich communities that have flourished in their walls.

“When people stereotype SROs, they imagine terrible living conditions and people you should pity,” he said. “But I’ve learned it’s more nuanced. A lot of residents actually enjoy living here. They have desires, fears, cravings — and a complexity people don’t see from the outside. When you move in, you realize it’s not a monolith.”

His personal experiment has also drawn wider interest. The Chinese Historical Society of America has asked Huang to help document SRO life through photos, videos, and writing, potentially for a future exhibition, as the number of big families living in SROs shrinks.

“I want to dig up the humanity of these people,” he said. “I want to share stories that transcend race and nationality. This is about common humanity.”

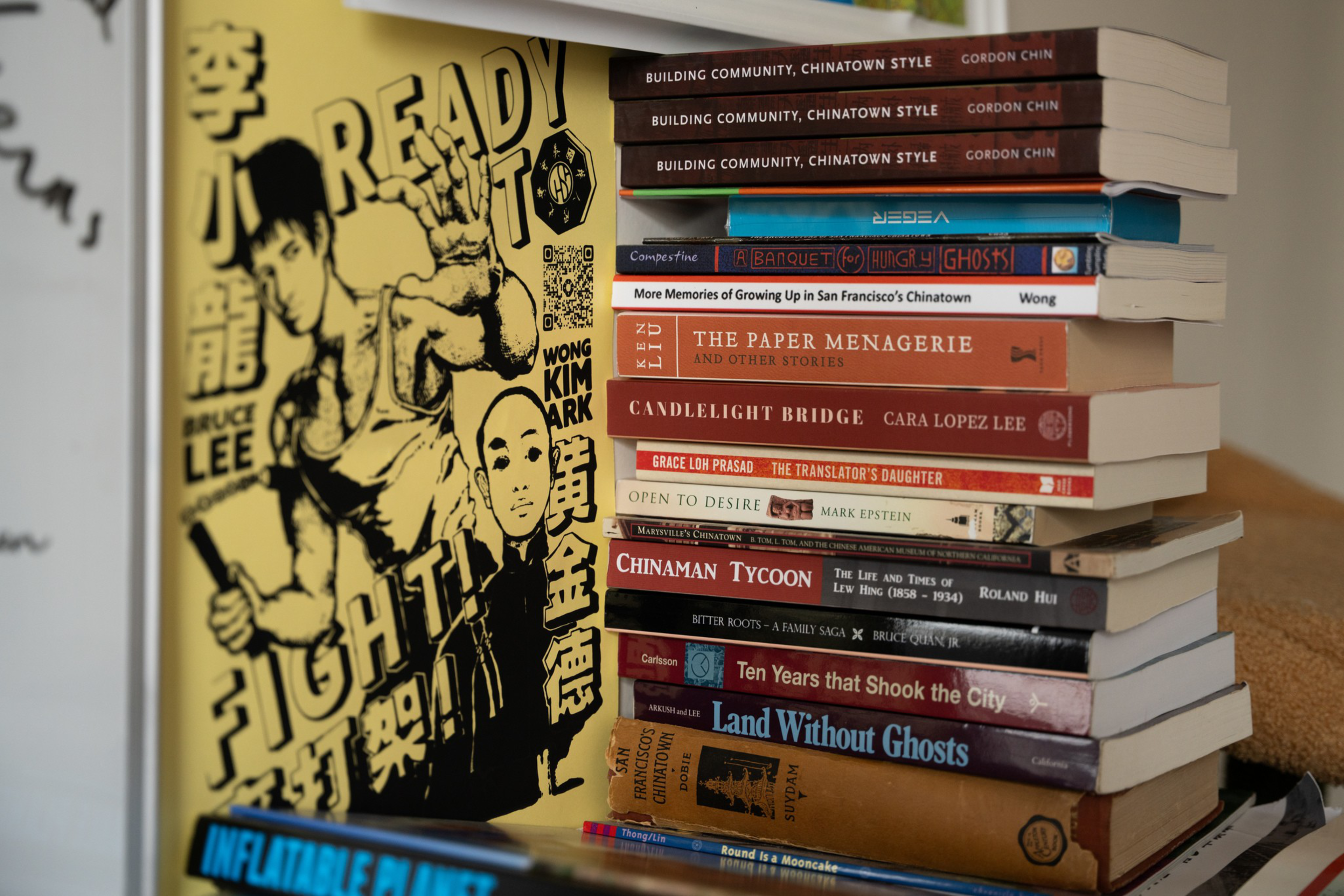

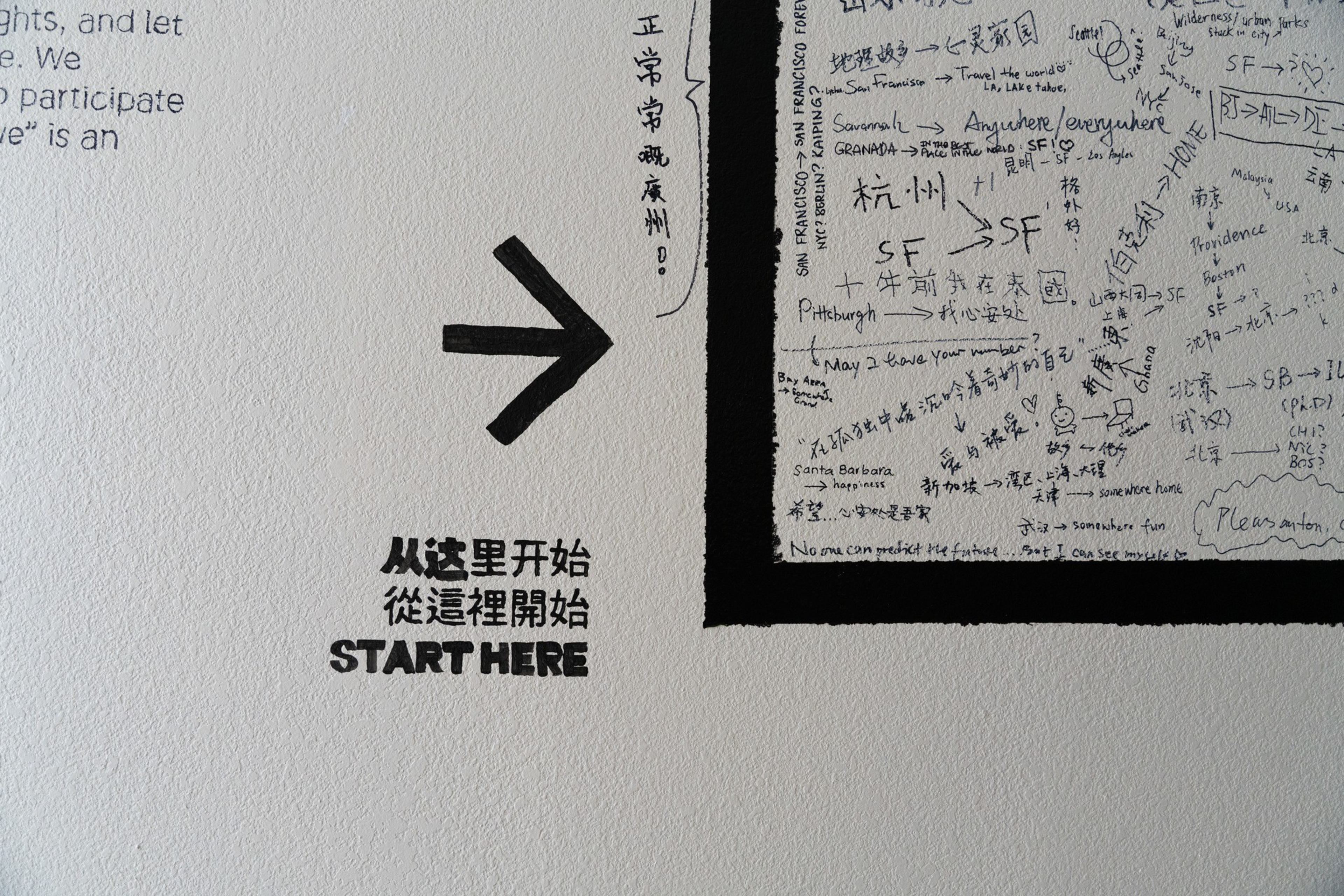

Huang’s experiment has since expanded beyond the SRO. He and about 20 Chinese immigrant friends are now preparing to open a bookstore called “Unbound” (格外) in an 850-square-foot storefront they recently leased across the street from his building. The shop will feature Chinese-language books and serve coffee, which he hopes will become an inclusive neighborhood space.

On Wednesday, Huang’s bookstore was buzzing with construction workers rushing to finish work before its projected opening in early November. Huang’s friends have decorated one wall with poetry, stories, and other random musings written in pen.

Huang said his SRO adventure will eventually come to an end, but he plans to extend his lease into early next year. After that, he is sold on the idea of staying in Chinatown as a “very embedded member” of the community.

“I’m totally happy to stay here indefinitely. I can see how I can make it work for me in the long term. It’s doable.”