Want more ways to catch up on the latest in Bay Area sports? Sign up for the Section 415 email newsletter here and subscribe to the Section 415 podcast wherever you listen.

In a way, Andrew Luck and Ron Rivera are just like everyone else.

“We’re all fans of our alma maters,” said Luck, the decorated Stanford quarterback turned general manager. “I’m no different.”

Luck, a four-time Pro Bowler, took his seat in Stanford’s newly minted GM’s office last November. Rivera, a two-time NFL Coach of the Year and a Super Bowl champion as a player, assumed the same role at Cal in March.

The Standard had the rare opportunity to speak exclusively with both leaders in the middle of their first season to see how they’re approaching a high-profile job that didn’t exist until a year ago.

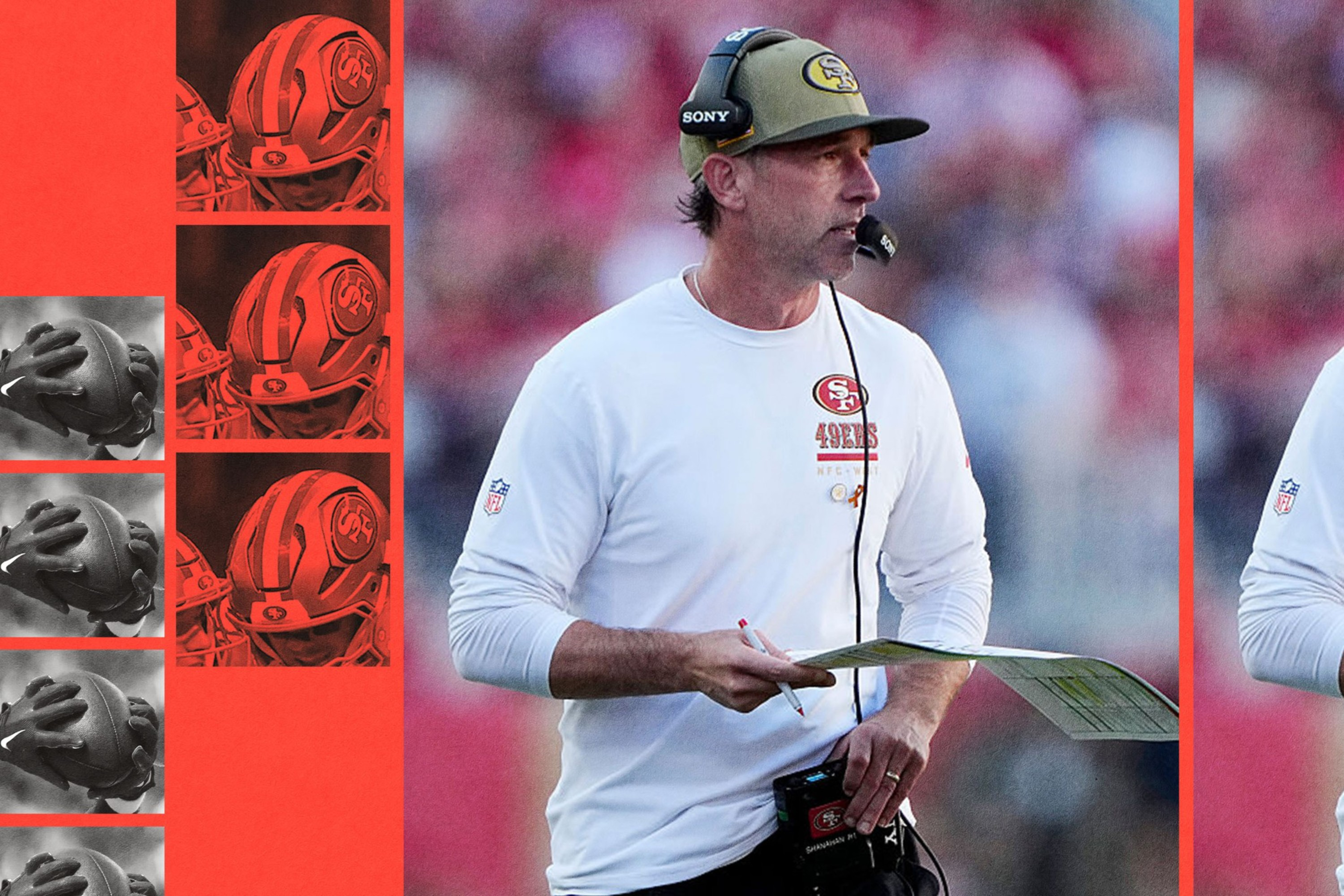

Section 415: Brock Purdy, Mac Jones, and the 49ers’ path to the playoffs

Section 415: Making sense of the Warriors’ uneven start

Section 415: How Natalie Nakase turned the Valkyries into an immediate force

Both Luck and Rivera view football as a vital gateway to draw eyes, energy, and resources toward the broader missions of Stanford and Cal. But the two former stars are taking markedly different approaches to accomplishing these long-term goals.

For Rivera, with Cal “on the precipice of the next big step,” he is more focused on building a memorable game day experience on campus and restoring the program to national prominence.

His priority list: capturing the East Bay market, filling seats in Memorial Stadium, and keeping TVs nationwide turned onto Cal football. In his time in Berkeley, Rivera’s emphasis is on boosting “community” — the kind of support that will inspire donations that fuel player retention.

“If we can become beyond relevant, we can generate the kind of revenue that can help ease the burden of the university,” Rivera said. “Athletics does raise the visibility of the university as a whole, that’s something to be realistic about in helping the university, and that’s what we’re trying to do right.”

Luck, on the other hand, has a somewhat more modest vision, one focused entirely on football performance.

“At the end of the day, I sit in charge of a football program, not a concert promotion business or another version of entertainment,” he said. “Our product is football.”

For both Rivera and Luck, the first order of business — the easiest part — was simply putting into words their respective visions for future success.

“Core to our identity is the pursuit of excellence. I don’t just say excellence, I say the pursuit — the totality, the journey,” Luck said. “Building a championship culture, being in a position to win championships, that is absolutely within our reach.”

In Berkeley, Rivera shares that same conviction. And he feels like Cal’s momentum at the outset of the 2025 season has set the stage for a brighter future. “This program had a storied history, at one time,” he said. “This program was headed in the right direction; we want to relive that. We want to bring that back to Berkeley.”

The rival GMs are now halfway through their first seasons, and the results have inspired cautious optimism in their respective fanbases. Cal is 5-2, with its best start under Justin Wilcox; Stanford is a more modest 3-4, but has already matched its win total for each of the past four seasons.

But the end-of-October box scores tell only part of Luck and Rivera’s unfolding stories. More measurable is their embrace of NIL revenue-sharing in striving to fuel their programs with fresh capital. Their efforts have inspired a wave of donor support unprecedented in either program.

Earlier this month, a $50 million donation to the Stanford football program from former player Bradford M. Freeman changed the athletic department’s financial outlook. Luck says the gift lays the foundation for a sustainable future in football that, in turn, supports the university as a whole and its storied Olympic sports.

“We consume football in this country at a scale that no other sport or piece of entertainment provides,” said Luck, who remembers being introduced to Stanford when he watched the Cardinals upset over a No. 6 Texas team in 2000 on TV. “So, having a competitive, quality team connects us with tens of millions of people across this country, ones that otherwise might not know anything about Stanford University.”

Luck and Rivera’s passion for their programs stems from shared experiences. During their pro careers, the duo spent countless days staying up late in the Eastern time zone to catch the first half of games, only to wake up to their phones pinging with the aftershocks of disappointing results.

The more time that passed since he played at Stanford, the more Luck saw a program that was becoming unrecognizable to him — and to itself.

“I certainly maintained as much passion and vigor for rooting our guys through it, but it was tough to see,” Luck recalled. “Stanford, we struggled to be proactive and assertive in carving out who we wanted to be and how we wanted to do it. Certainly, coming out of Covid seemed to be difficult, across higher education in general, not just football.”

Across the Bay, the fate of Cal football was even harsher, one of enduring darkness — or the flickering light of mediocrity — as the team spent the better part of three decades “lacking identity and resources,” according to Rivera. Since leaving Berkeley after an All-American season with the Bears in 1983, and through a pair of NFL head coaching stints with the Panthers and Commanders, Rivera clung tightly to Cal’s exhilarating rise during the Jeff Tedford era. Those years, between 2002-2012, were “a great source of pride.”

But the program hasn’t seen an eight-win regular season in 15 years. Some elation, joy, thrills, and talented players — but mostly disappointment.

At some point, for both Luck and Rivera, witnessing the stumbles from afar became less about sounding off frustrations in group chats with former teammates and roommates and more of a call to action.

With a coaching transition on the horizon at Stanford, it makes sense that Luck’s mission focuses more on the Xs and Os than Rivera, who has expressed confidence in Wilcox’s leadership.

After firing Troy Taylor last spring and bringing in his former Colts coach Frank Reich on for a one-season interim period, Luck’s day-to-day responsibilities on the job include rebuilding the program’s culture and staff — a particular aspect that Rivera has (not yet, at least) been tasked with.

“Time is a zero-sum game,” Luck said. “I’m learning on the job … to toggle between continuing to provide and help co-create the right environment for our program and staff to thrive in, continue to have an eye on the future, fundraising, recruiting, and preparing. And preparing for the next head coach.”

Luck admits that he would also like a head coach who can consistently beat Cal. But it wouldn’t hurt if the Bears teams they beat are really talented too. With another round of conference realignment on the horizon after the Big Ten’s media rights deal expires in 2030, the schools could be better positioned to seize opportunities to move if both have strong football programs.

“You won’t hear me say too many nice things about Cal,” he laughed. “Don’t take my respect for them as I like them, because I really don’t. But iron sharpens iron. And capturing this market and giving our communities big-time college football is important to both of us.

Rivera agrees and doubles Luck’s enthusiasm. “For the two of us — Cal and Stanford — we have to capture it,” he said. “At the end of the year, every time Cal and Stanford play, you want that game to be impactful and important”

For both schools, that’s the challenge: to make late November’s Big Game matter again outside of the alumni who will always tune in to watch their alma mater from afar. It has to matter to all of college football.