In mid-August, days before the start of the school year, the mother of a soon-to-be freshman at Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts wrote a frantic email to Matt Wayne, superintendent of the San Francisco Unified School District, and others she thought might be able to assist her child.

Acting on advice from school officials, the student had twice taken extracurricular algebra courses only to be told, twice, that the courses didn’t confer eligibility for geometry. “How can this district do this to my child?” the parent wrote.

Unlike so much of what’s going on with the city’s public schools, however, this tale has a happy ending. The district’s “central office” intervened. The child was admitted to geometry. But behind the scenes, the incident provoked a telling give-and-take between the SFUSD’s staff and Lainie Motamedi, then president of the school board.

“How many students requested to take a 9th-grade math class other than algebra?” Motamedi emailed several staff members, blind-copying the entire seven-member Board of Education. “Can we confirm students making a request for a course other than algebra have had their requests reviewed correctly and placed accordingly? What is the process for review? What is the process for student/family appeal of placement?”

The staff’s response illustrated the dysfunction that plagues so many of the district’s operations and shows why SFUSD, after years of turmoil, is no closer to salvation than before.

“We do not have data on how many student requests we had for a non-algebra course because this is handled at each site,” a staffer responded — “site” being SFUSD jargon for “school.” The response continued: “Collecting this data has not been something as of yet that we have developed a system to collect. Since we do not have a tracking system we cannot confirm that all requests have been reviewed correctly. There is not a formal process for review in place currently.”

It’s just one example of the district not having a handle on the most basic aspects of operating its schools. But there are countless others.

“The district is siloed and decentralized,” Elliott Duchon told me last week. Duchon is the powerful state-appointed adviser to the district who has the authority to reverse board-approved spending measures. He has witnessed firsthand the dysfunction within the district’s administrative offices. “The district stresses everybody around it,” he lamented, noting that the central office and the schools often “don’t talk to each other.”

Eight days after sending the geometry email, Motamedi abruptly quit the board, citing the need to tend to her health. But her testy exchange with the staff spoke to another likely reason for Motamedi’s resignation: her utter frustration with Wayne’s management.

Unfortunately, the board president’s departure came at the worst possible moment for the district and the board she led. The district faces a crushing fiscal crisis and an imminent announcement that it plans to “consolidate” — i.e., close — as many as 14% of its schools.

Even that “realignment” unveiling hasn’t gone as planned. Late Sunday afternoon, Wayne said the district is pushing back its decision, which was supposed to come this week, until an unspecified date in October. He said the delay is necessary to ensure that “we meaningfully consult with city, school, and community leaders.”

Anyone following the months of intense planning for what is certain to be a fractious and bitterly contested decision knows the absurdity of that excuse. School bureaucrats said in June they already had held two virtual town halls with 1,000 participants, 16 in-person community sessions with 1,070 participants, and six information sessions with community-based organizations that attracted 291 attendees.

The sad truth is that the closures, while absolutely necessary, are merely the tip of the iceberg for a school system that is out of money, poorly run, and insufficiently educating its children.

The crises mount

Anyone who isn’t clear on why San Francisco needs to close schools isn’t taking the time to look at how inefficiently the buildings themselves are being used. According to district data, just 20 out of 72 elementary schools are more than 90% occupied. Eight of 21 middle schools and a mere five of 17 high schools meet that measure.

Meredith Dodson, head of the advocacy group San Francisco Parents Coalition, said district officials have told her the closure list will number between 10 and 15 schools. But that was before the postponement announcement. Duchon, the state-appointed overseer, claimed to be in the dark on closures. “We’ve asked for fiscal information and the cost of implementing the plan,” he said.

Costs are the next headache the district will confront. In June, the district presented to the board a proposed list of budget cuts totaling nearly $114 million. A spreadsheet detailing the cuts included eliminating bus transportation for general-education students (a $2.6 million annual savings) and a $10 million reduction in spending for special education. Someone familiar with such reports told me that they usually include a description of how fiscal measures will affect students. “A $10 million cut in special education would warrant a whole plan of its own,” this person said.

The closures and the fiscal crisis have gripped the district to the point that other decisions have been put on hold. For example, four years ago the board approved a policy to begin to re-prioritize the neighborhood where students live in selecting where they go to school. The district says it won’t reveal details of how this will work for elementary school enrollment until it deals with closures.

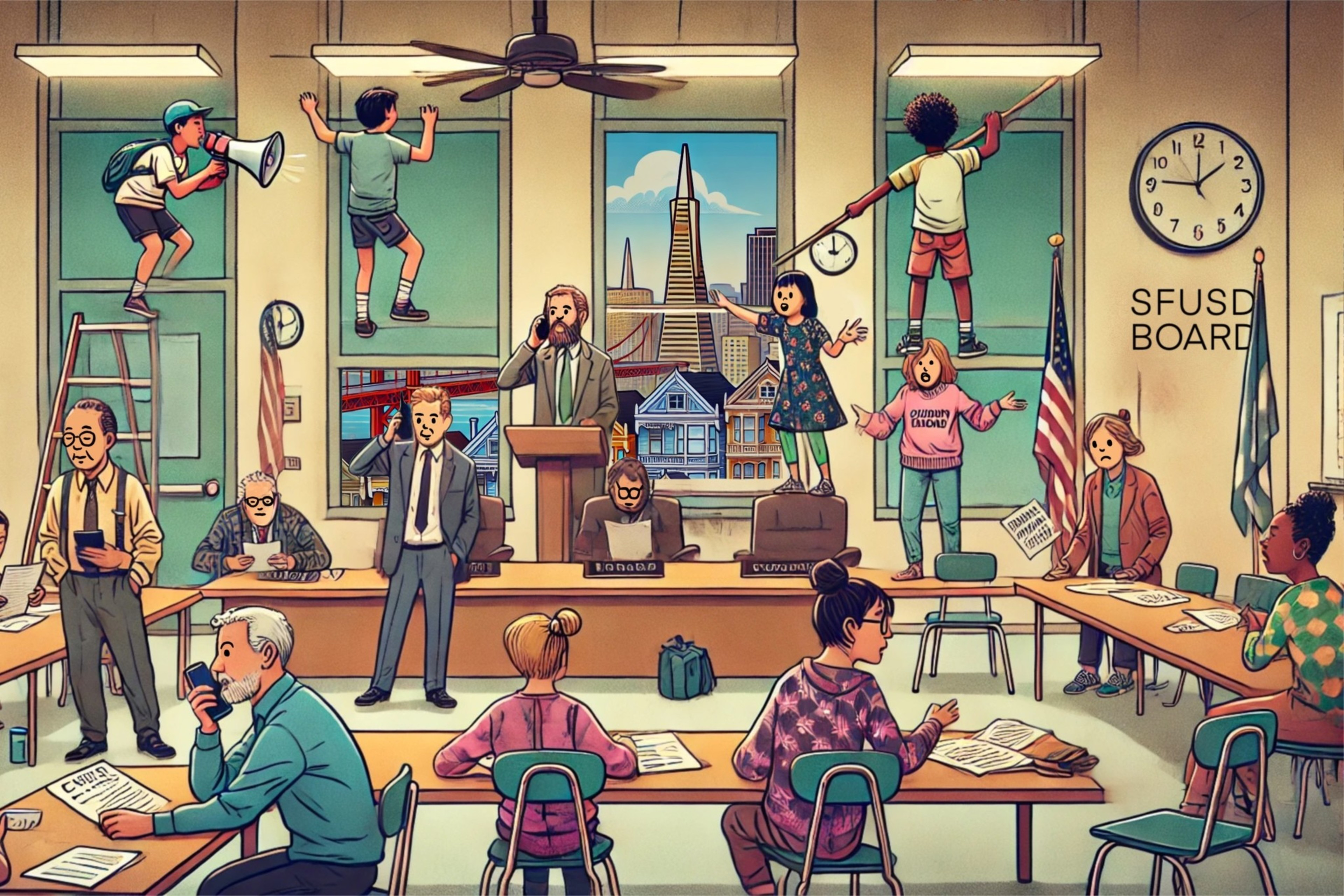

Then there’s the board itself, which is still far from a well-oiled machine two years after a contentious recall campaign ousted three members. In 2022 the board resolved to increase the time it spent in meetings on “student outcomes.” That’s edu-speak for talking about children instead of adults. At the time it was spending, by its own estimate, only 0% to 5% of its time talking about kids in each board meeting, and it set a goal of 50%. It has gotten to 35%.

Privately, the district and its board have been reaching out for help. This summer, the Silver Giving Foundation, which focuses on public schools, paid for Ben Rosenfield, the former controller for the city of San Francisco, to write a study for the board and the district on how to improve its processes and procedures.

Rosenfield produced a memo whose contents haven’t been made public. Those who have seen the memo tell me that it echoes a two-year-old document of “observations and recommendations” the state shared with Wayne early in his tenure, chastising the district for relying on one-time deficit plugs, inadequately adjusting to declining school enrollment, and having poor overall operational controls.

In other words, two long years into a well-understood crisis, the district continues to flounder even as its problems worsen.

One person who likely will own those problems for some time to come is the superintendent, Wayne, whom the district didn’t make available for an interview. In May, the board extended his three-year contract by a year (opens in new tab), to June 30, 2026, saying that according to the terms of his agreement, he had received a rating of “satisfactory” or above during the 2022-2023 school year.

From the outside looking in, it’s tough to imagine what about Wayne’s performance has been satisfactory. Perhaps grade inflation is as much of an issue on the board of education as it is in so many classrooms.