The last time there was a political earthquake of the magnitude we just witnessed within San Francisco’s City Hall, Daniel Lurie was an 18-year-old recent graduate of University High School. That was way back in 1995, when Willie Brown beat the incumbent Mayor Frank Jordan, ushering in a bold new regime to run the city. The next three elected mayors — Gavin Newsom, Ed Lee, and London Breed — were all appointees or protégés of Brown, effectively representing an uninterrupted run of Willie’s World.

This nearly 30-year political epoch has left the so-called City Family unprepared for the election of Lurie, who ran explicitly against several of its own. Most current department heads and staffers have neither the playbook nor muscle memory of how to function outside of the patronage army that Brown built.

To put it another way: This is the first administration in a generation that owes Brown and the rest of San Francisco’s political firmament precisely nothing. (A while back, I heard that when Lurie asked Brown for campaign advice, the wily politician dismissively responded that the philanthropist should “get a job.”)

“City Hall insiders,” as Lurie repeatedly derided them during his campaign, have no idea what to expect. Will the new mayor clean house and install his own loyalists in place of longtime officeholders? Will he swing a sledgehammer at city government’s byways, taking down anyone who stands in his way? Lurie spoke repeatedly of City Hall’s dysfunction during the campaign, and his victory letter (opens in new tab) cites “shaking up the corrupt and ineffective bureaucracy” as one of his top priorities.

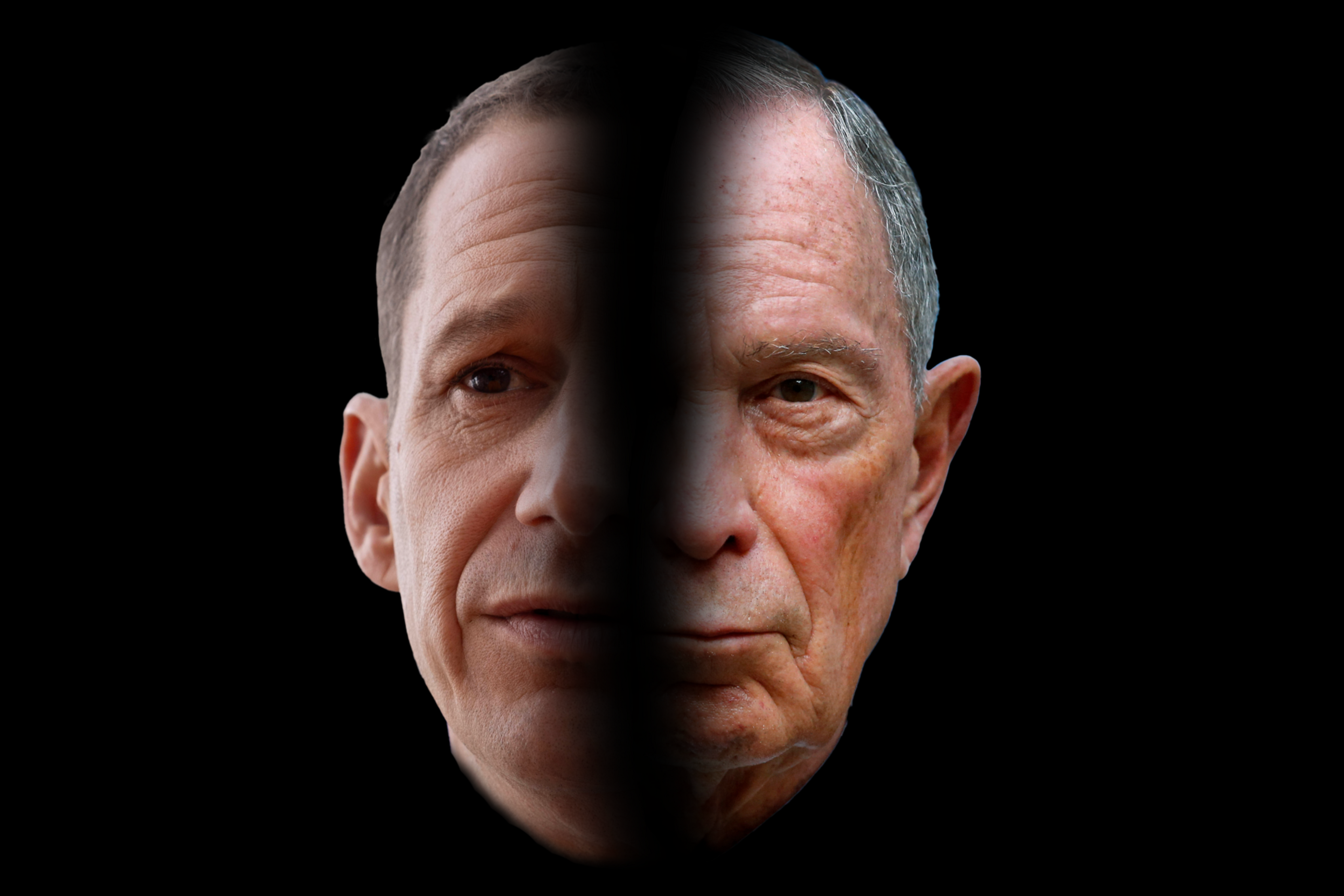

Lurie named his transition team Monday (opens in new tab), a group that includes OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, and a handful of politicos. But as he thinks about the kind of leader he plans to be, he’d be wise to consider the obvious and laudable example of another iconoclastic big-city mayor: Michael Bloomberg.

When the financial information executive took office in New York City in the months after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, he too was a rich guy who had never been elected to anything. Like Lurie, he had begun his campaign far down in the polls and was widely expected to lose to a veteran politician, Public Advocate Mark Green.

And like Lurie, Bloomberg enjoyed the political flexibility that comes from having financed his own campaign. Though he won the last-minute endorsement (opens in new tab) of Rudy Giuliani, then highly respected as “America’s mayor,” few of New York’s power players endorsed Bloomberg.

That’s true for Lurie, too. In fact, Bloomberg himself didn’t back Lurie’s run for mayor; instead, he gave $1.2 million to the Breed campaign.

‘No allegiance to anybody’

In the 2000s, Bloomberg’s financial independence gave him a free hand to assemble a team in his own image, regardless of whose backs they had scratched before. “He had no allegiance to anybody,” recalled Dan Doctoroff, a powerful deputy mayor for economic development under Bloomberg, who came into government with little political but plenty of private-sector experience.

A seasoned investment banker, Doctoroff had led a failed effort to bring the Olympic Games to New York, which he retooled into a grand redevelopment plan for the city. When Bloomberg won, Doctoroff was reluctant to sign on. “I turned him down twice,” he told me via Zoom last week. “Eventually I met with Mike, and he convinced me I could do everything I wanted to do more effectively inside City Hall.”

In the wake of Lurie’s election victory, I spoke to former Bloomberg administration officials who said the mogul–mayor’s independence more than compensated for his inexperience. “Not owing anybody anything is a huge benefit if you play things right,” one told me.

Peter Madonia, Bloomberg’s first chief of staff, said the mayor was liberated by not needing to repay campaign favors. “He was quite clear to me,” Madonia remembered of his boss. “He said, ‘Go find the best and the brightest.’”

Bloomberg famously recruited businesspeople in his own mold, including Doctoroff and Andrew Alper, a former Goldman Sachs partner he tapped to run the New York City Economic Development Corporation. But he named — and retained — plenty of seasoned hands, too. “Mike understood he needed people who had government experience at a high level,” said Madonia, himself a former official in the administration of Mayor Ed Koch.

Among the city officials Bloomberg retained were the heads of the prison, taxi regulation, and transportation agencies. His first deputy mayor for operations, a key post in New York, had held multiple city jobs before going to work for Bloomberg.

The new mayor went out of his way to praise municipal employees, even knowing a multibillion-dollar budget deficit would require painful cuts. (Sound familiar?) “He expressed tremendous respect for city workers,” said Ed Skyler, initially Bloomberg’s press secretary and later a deputy mayor for operations. “He went to union leaders and said, ‘I’m going to work with your members to make the city better.’”

Bloomberg was clear on his vision for the city, which featured some of the same priorities Lurie has today, including boosting public safety and building affordable housing. The New York mayor was equally clear about a few quirkier initiatives, including a ban on smoking in public spaces.

Madonia said he pushed back on Bloomberg over the smoking ban, given the more pressing matters the city faced. “I said, ‘What the fuck do you want to do that for? We’ve got to lay off sanitation workers and correction officers and close firehouses.’ But he was resolute about it, and to his credit, he was right. It became a global success.”

For all the similarities, there also are considerable differences between the two upstart mayors and their cities. By the time he became mayor, Bloomberg was a self-made billionaire and exceedingly capable CEO, with a reputation for leading deftly while delegating broadly. In the words of one admirer, “Mike is in a league of one.”

Lurie, by comparison, has far less operating experience than Bloomberg. His management highlights include running a 50-person non-profit and serving as the chair of the Super Bowl host committee. (Fun fact: Lurie modeled the nonprofit he founded, Tipping Point, on the organization where he worked in New York, Robin Hood, during the first years of the Bloomberg administration.)

Lurie’s disadvantage

Bloomberg had another significant advantage over his San Francisco counterpart. New York’s mayoral system is so centralized that nearly every powerful player in the city government reported directly to him. This meant Bloomberg’s lieutenants kept a firm hand on city affairs.

“I drove the agencies to cooperate and collaborate,” said Doctoroff, who has studied San Francisco’s governance and notes. “We had a lot more power.” (Doctoroff pointed out that at least one member of Lurie’s transition team, Sara Fenske Bahat, worked for him in New York.)

Though San Franciscans debate the strength of the mayor’s office, it’s a fact that the city government’s reporting structure is byzantine, with many departments operating as independent fiefdoms with long-tenured heads. Some department chiefs can be hired or fired by powerful commissions, while other top officials report to the city administrator.

As an example of how complicated things will be for Lurie: City Administrator Carmen Chu, who is three years into a five-year term that ends in February 2026, oversees 25 departments, divisions, and programs. Should Lurie want his own person in the post, he could remove Chu, but only with the approval of the Board of Supervisors.

Most City Hall prognosticators I spoke to believe Lurie will be able to put in place the people he wants, though perhaps not as quickly as he’d like. They expect the mayor-elect to look to the types of high-powered businesspeople who populated the board of Tipping Point (opens in new tab). This in itself would constitute a major change — San Francisco has little tradition of well-off corporate titans joining city government for relatively paltry salaries.

Word is that Lurie is casting a wide net. Ironically, he could be assisted by the return of Donald Trump, which has meant there are oodles of talented Democrats, in California and nationally, who may be interested in a job. Until Nov. 6, these players were packing their bags for Washington to serve in a presumed Kamala Harris administration. Now they are considering their options.

As for those currently in top City Hall roles, they are bracing for impact. Last week, each city department submitted a memo for the new mayor detailing its operations and priorities. One wag in City Hall told me these documents will function as preliminary job interviews for department heads hoping to stay on.

Given the many congruences between the Lurie and Bloomberg stories, the question City Hall insiders will be asking in the coming weeks is to what extent Daniel can be like Mike. Will he make nice with the old guard while integrating some of the new? Or will he clean house and make way for an all-new City Family?

The bureaucrats of San Francisco uneasily await the answer.