If we want better government, we need to be able to measure success — and reward it.

That’s why I proposed — and our San Jose City Council just took the first steps (opens in new tab)to approve — a novel no-raises-without-results reform. It will reward politicians and key government employees with raises only if we make measurable progress on key issues, such as safety, homelessness, and economic growth. And yes, that includes me. After one more vote of our City Council in June, we will seek the necessary ratification by San Jose voters next year.

I came into government service from the tech startup world, where incentives are very clear. If your business is delivering value, you are rewarded. If you don’t meet the needs of customers, you fail.

What shocked me upon joining local government is that there were few serious performance-improvement plans in place and little articulation of how we measure progress.

That’s why one of my first acts as mayor was to reduce a sprawling priority list to four focus areas: improving safety, ending homelessness, cleaning up the city, and attracting investment in jobs and housing. I also established a plan to track performance metrics such as crime rates, homeless residents who transition into housing, cleanliness of neighborhoods, and other measures that reflect residents’ priorities. These metrics are now available in a public-facing dashboard (opens in new tab) that shows the public our progress — or lack of progress.

The next step is tying the performance of elected officials and top administrators to progress in these areas. For example, I would like to see us reduce homelessness by 10% every year. Those whose jobs are directly tied to making this happen would have performance goals related to this result. Our Public Works director’s performance-based raise would be proportional to the number of interim housing units delivered on time and on budget. Our housing director’s pay increase would be tied to the percentage of prevention dollars distributed to needy families, and so on. Any increase in my own pay would also be tied to measurable progress on the top-priority goals we set through the budget process each year.

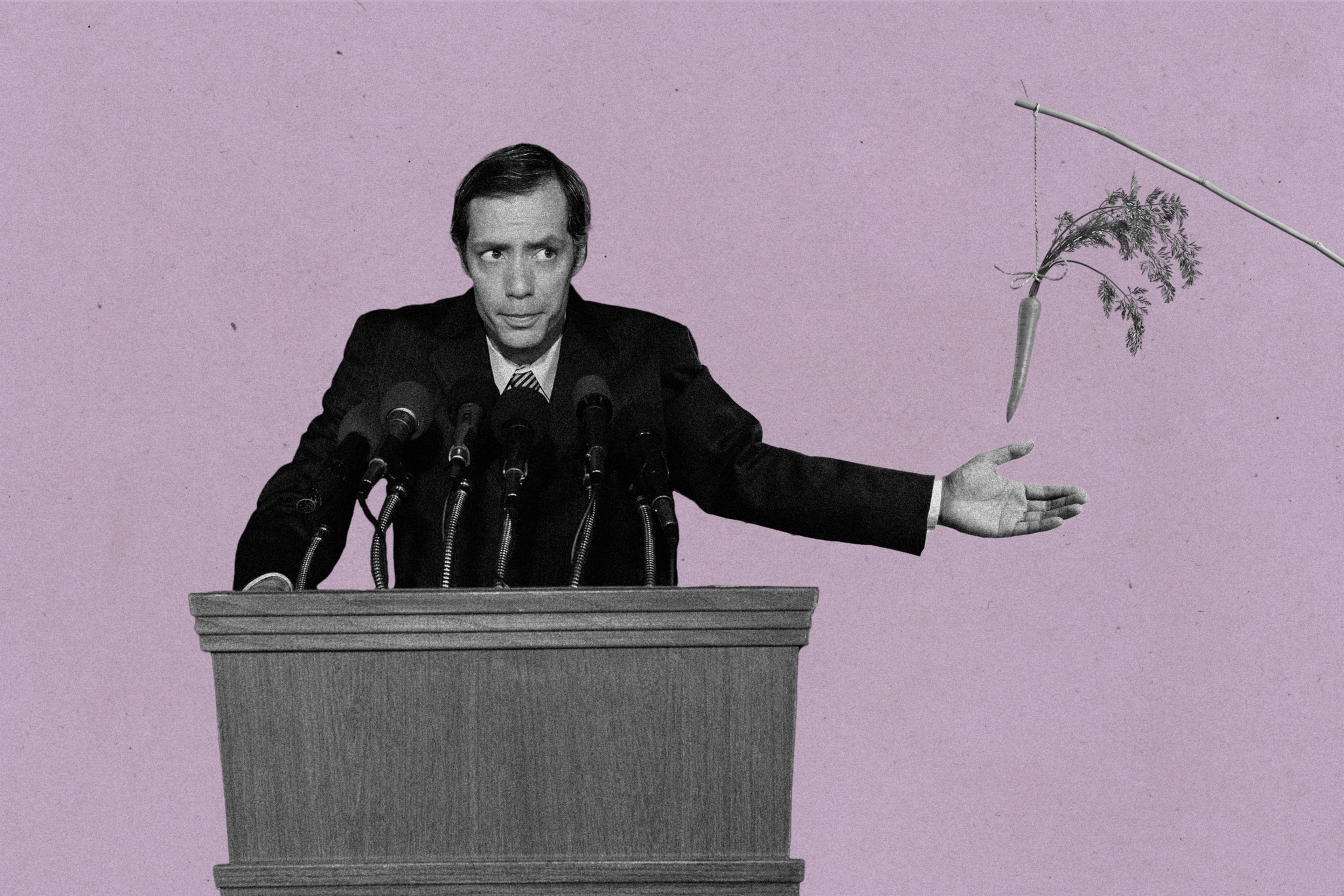

Unless the people most responsible for better government — the politicians (myself and the City Council), our city manager and her key deputies, and all department heads — are delivering progress, we should not earn pay raises.

Something similar has been tried before in California, and it worked. In years past, our state budget was perennially late because legislators ignored statutory deadlines. Reformers proposed that if a budget were late, the Legislature would not get paid. Since that reform was enacted 15 years ago, all state budgets have been delivered on time — with a caveat. The members of the state Legislature made themselves the arbiters of record, often passing sham budgets to save their pay. We’ve learned from this, and pay raises for the San Jose City Council will not be determined by the council but by a salary-setting commission that will receive annual impact reports and make compensation decisions.

Three years ago, I defeated a candidate backed by the local political establishment, with “Pay for performance” at the center of my campaign. What struck me was just how controversial this common-sense idea was to those in government.

Many of the very people who speak passionately about how our government must help the most vulnerable strenuously opposed a plan to make sure it did so more effectively.

Public-sector productivity increases have failed to match the dramatic increases we have seen in the private sector over past decades. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that nonfarm private-sector productivity has grown at an average annual rate of 2.1% since 1973. In contrast, a recent Brookings Institution report found that public-sector productivity grew at an anemic 0.5% rate.

Why are private-sector workers getting better four times faster than those of us in government?

Our system is biased against meaningful change. Interest groups focus great resources on electing allies who are disinclined to question how the government works. Rather than solving problems, we often pay consultants and nonprofit contractors to manage them. Perhaps most crucially, public-sector pay raises are all but guaranteed, whether or not we move the needle on our biggest challenges.

I’ve been asked if my program is the Democratic version of DOGE. We certainly share the goal of better use of taxpayer dollars. But we proposed our plan three years ago, inspired by a desire not to gut the government but to improve it, particularly for those who need government most.

Every party that says it speaks for hard-working Americans and those being left behind should fully embrace the idea that we are responsible for making the government better. To do that, we should no longer tolerate, much less reward, failure.

Matt Mahan is the mayor of San Jose.