A recent San Francisco Standard article about Stanford students’ apparent pivot toward careers in military technology sparked fiery memes (opens in new tab) and other online reactions. Many students scoffed at the assertion that those starting their careers at Palantir or Anduril are “moral and effective.” But as Stanford students, we shouldn’t be surprised: Most graduates of elite universities do pursue careers that put prestige and money over public good.

Case in point: I came to Stanford to study and fight the climate crisis. Yet, as a sophomore, I found myself applying to spend my summer at Goldman Sachs, a bank that has $19.44 billion in fossil fuel investments (opens in new tab) and employees who work an average of 98 hours a week (opens in new tab).

Around the same time, I watched a friend who had vowed never to work for McKinsey suddenly apply for a summer internship. I felt crazy, like we had been possessed to chase jobs that fundamentally contradicted our values (opens in new tab).

You don’t get into Stanford or any elite university writing about your dreams of becoming an investment banker, management consultant, or military drone engineer. After all, the student quoted in the March 12 article said “she didn’t dream of one day working in national security.” Stanford claims to want big thinkers, changemakers, and do-gooders — people who will advance the founding mission (opens in new tab) of the university to “promot[e] the welfare of people everywhere.”

Yet 54% (opens in new tab) of us go into careers in technology, consulting, and finance — fields known for high salaries, not for promoting the welfare of others.

What happens between the time we write about our world-changing aspirations as high school applicants and the time we exit Stanford with high-earning job offers in finance, consulting, tech, and arms technology?

It turns out that students at other elite institutions were calling out this phenomenon at least 15 years ago (opens in new tab). And 10 years ago, it got a name: career funneling (opens in new tab).

Here’s how it works. As the “best and brightest” students, we are the crown jewels of the world’s most lucrative companies, from Deloitte to Goldman Sachs to Palantir. These companies have developed sophisticated tactics (opens in new tab) to convince us young career professionals that they have the jobs we want and deserve, and their massive recruitment budgets allow them to monopolize attention on campus, outcompeting potential employers who lack the same resources.

High-wealth firms know how to capitalize on our uncertainty and anxiety about our future, offering “stable” options with early recruitment cycles. They capitalize on our competitiveness with coveted recruitment spots and on our status-consciousness with competitive pay.

And if we make it to the final interview, they fly us to New York to stay in luxury hotels and give us several hundred dollars to spend for the weekend — all to give us a quick taste of the high-roller lifestyle (opens in new tab).

Career funneling has far-reaching effects. How can we possibly tackle the defining issues of our time — the climate crisis, widespread inequality, an eroding democracy — when we’re strapped with 60-plus-hour work weeks as consultants, tech engineers, and private equity analysts?

Elite universities systematically advance career funneling. Stanford was one of the first to establish corporate partnership programs (opens in new tab). CPPs give companies expensive, special access to students, especially ambitious freshmen who are anxious to get their hands on a high-caliber internship ASAP as newcomers to the ever-pervasive Stanford imposter syndrome (opens in new tab).

Procrastinating a socially impactful career isn’t going to do the trick. Research (opens in new tab) has found no evidence that high-wealth careers hold any advantage as launching pads to impactful work. We are being streamlined away from socially impactful jobs at the time we should be pursuing them the most.

Some of us choose jobs to support our families, but given that more Stanford students hail from the top 1% than the bottom 50% (opens in new tab), such students are in the minority. My parents, first-generation Turkish immigrants, worked corporate jobs that enabled them to immigrate to the U.S., financially enabling me to attend Stanford.

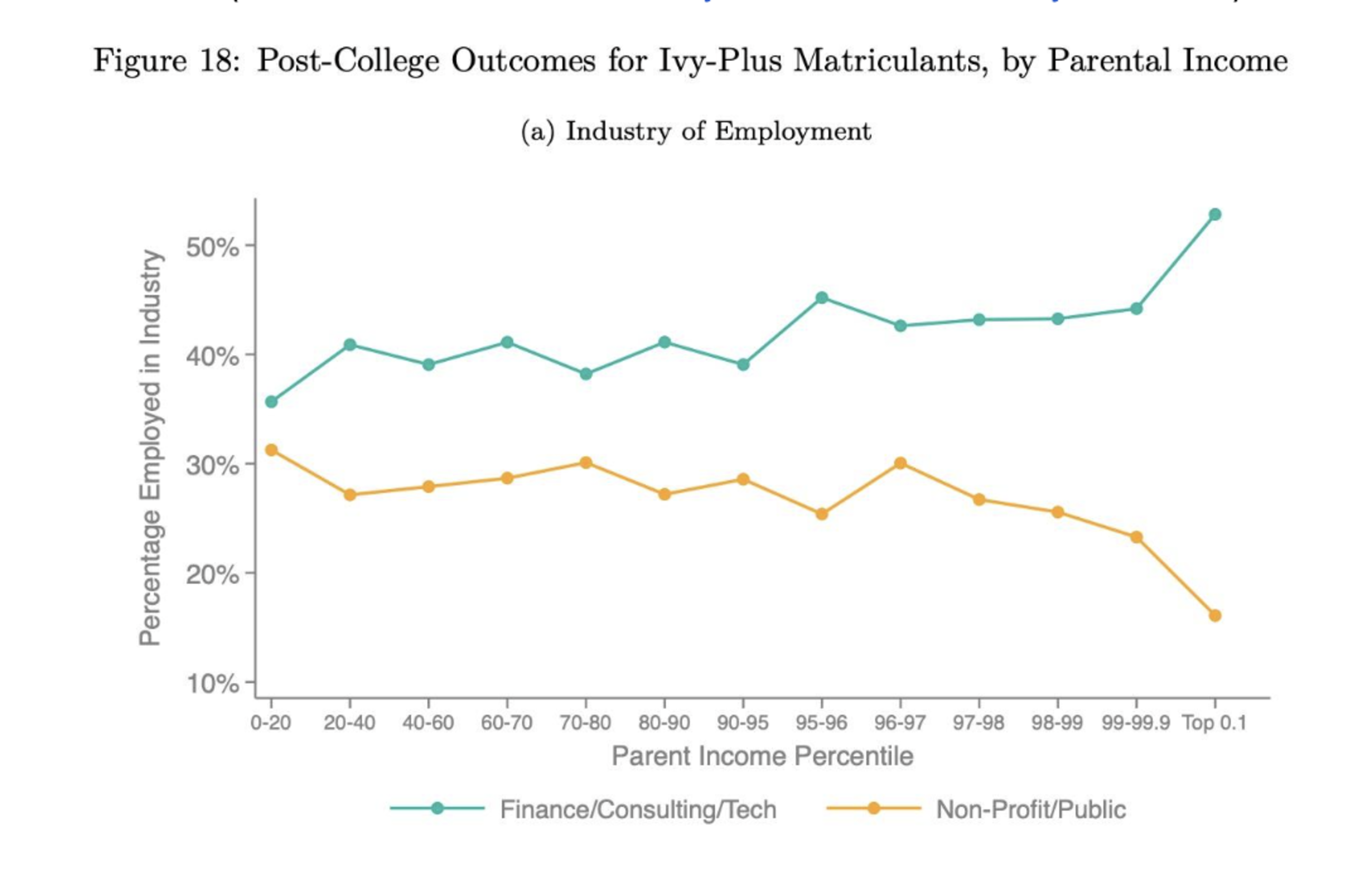

At Harvard, students from the bottom 90% of the income distribution are 1.5 times more likely to choose public-sector and nonprofit careers than those from the top 10% of household incomes (based on the 2024 Class Survey (opens in new tab) and economic diversity at Harvard (opens in new tab)).

Career choice is arguably one of the most important ethical decisions an individual will ever make. Most will spend 80,000 hours (opens in new tab) of their lives working on whatever vocation they choose — not something to approach casually or surrender to the allure of a six-figure salary. You owe it to yourself to thoughtfully interrogate the forces that made you grind so hard to get into an elite university — and those that brought you to McKinsey, Meta, or Palantir’s doorstep.

My friends who chose slightly unconventional paths — launching social impact companies, managing art studios, researching racial bias in AI, or expanding legal aid to underserved communities — have exemplified what it means to pursue meaningful work. Not coincidentally, they are much happier than my friends working hellish weeks in finance and finance consulting.

As it turned out, I was rejected from Goldman Sachs. In the summers that followed, I worked at a climate-focused venture capital firm and conducted research into the transition to electric vehicles. The place I least expected to be working, an educational farm in O’ahu (opens in new tab), inspired me to study and work in environmental psychology.

The bottom line: We shape our campuses through what we value. Rather than glorifying prestigious, high-paying positions — whether in military tech or on Wall Street or Sand Hill Road — let’s celebrate how we and our peers can contribute to society. An elite education is a privilege; as the fortunate few, we must do better.

Nazli Dakad is a senior at Stanford, and an organizer with Class Action (opens in new tab). Junior Alyssa Murray and senior Sebastian Andrews also contributed to this essay, which was adapted from a piece that originally published in the Stanford Daily (opens in new tab).