Local fans of Bruce Lee may be familiar with the pair of murals depicting the martial arts icon in San Francisco Chinatown—one near City Lights Bookstore on the edge of North Beach and the other on Commercial Street, just a short walk from St. Mary’s Cathedral.

There is now a third mural of the SF-born martial arts icon in town: Inside the Chinese Historical Society of America’s new exhibition, We Are Bruce Lee, which opens Sunday, April 24.

Within the exhibit, guests will be greeted by a shirtless Lee. His visage radiates power, as an overlaid light projection adds lava lamp-like bubbles and an electric glow to the already striking figure.

Inside, visitors will also find costumes from Lee’s movies, photos of Lee as a child and his birth certificate, which shows he drew his first breaths at Chinese Hospital, just over two blocks away from CHSA. A high-resolution screen plays clips from some of Lee’s movies. Another screen shows video interviews, including one with Shannon Lee, Bruce’s daughter, who talks about her father and his cultural influence.

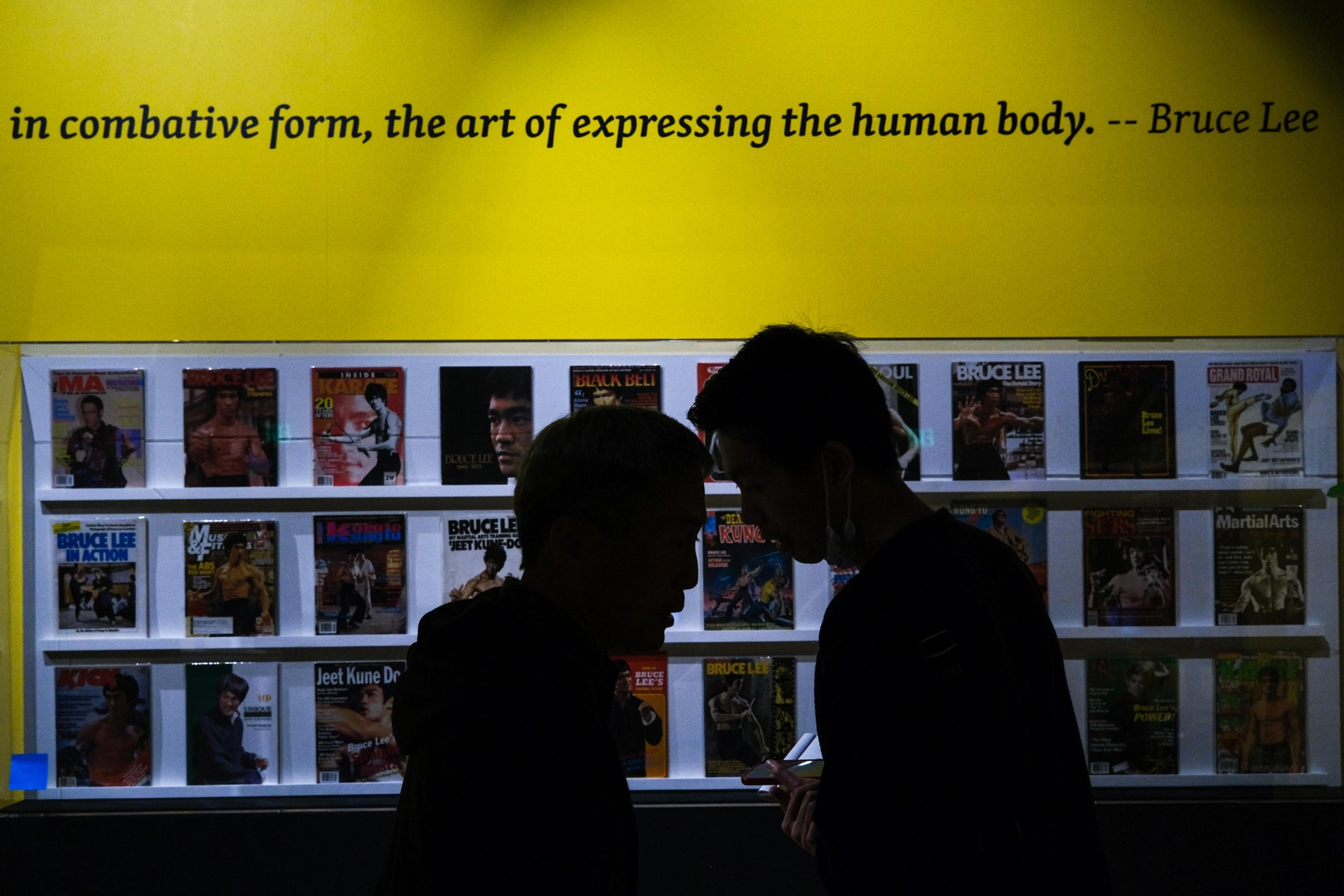

Through his roles in television and movies, Lee was instrumental in raising the profile of Asian martial arts in America. But his legacy stretches beyond his status as a Hollywood action star. Lee was also a hero of social justice, who used his celebrity to build bridges between disenfranchised and historically oppressed communities of racial minorities.

‘A Perpetual Foreigner’

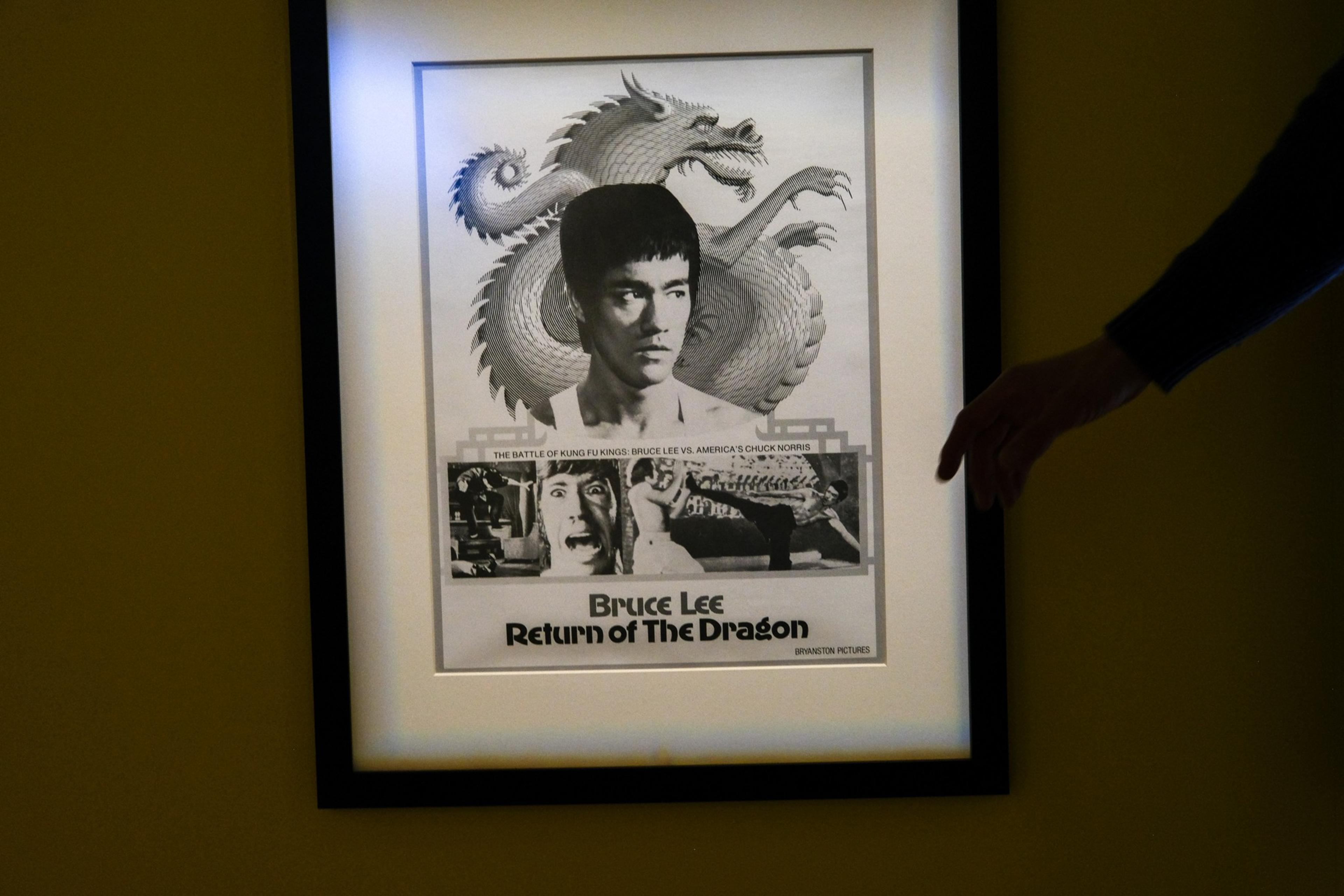

One noteworthy piece of ephemera in the exhibit is a promotional poster for The Way of the Dragon.

The poster, which belongs to Jeff Chinn—a local Lee superfan who loaned CHSA many of the pieces on display at the exhibit—features a telling caption, which reads: “Bruce Lee versus America’s Chuck Norris.”

“This is the prologue that introduces Bruce as a complex Chinese American,” Justin Hoover, executive director of CHSA, told The Standard during an exclusive preview of the show.

That the poster goes out of its way to identify Norris, a white man, as American is illustrative of the pervasiveness of institutional racism in the United States, Hoover said. Though Lee was an American citizen by birth, he was regularly painted as a “perpetual foreigner,” he explained.

Lee’s status as perpetual foreigner had a number of consequences. One of which, Chinn observed, was that he was regularly underpaid.

Another of the Bruce Lee-related artifacts that Chinn has loaned CHSA is an original copy of the payroll sheet from The Green Hornet—the 1966 action TV show, which starred Lee as “Kato,” the kung fu-kicking sidekick to the titular (and white) main character.

“Look at Bruce’s name and you look at the amount of pay, and then you look at everyone else,” Chinn said, calling attention to the fact that Lee—one of only a few Asian American actors working in Hollywood at the time—was the lowest-paid name on the list. “He was not treated equally,” Chinn added. “This is proof right here.”

Leading By Example

As a high-profile actor with a major platform, Lee helped Asian Americans like Chinn feel more comfortable in their own skin through his appearances on TV and in the movies. But he also made an impact off camera.

Working as a martial arts instructor, Lee insisted that the physical skills and philosophical underpinnings of kung fu could be taught to people of all races and backgrounds, including non-Asians.

When he was a young man, Lee lived and taught martial arts in Seattle. It was there that he met Jesse Glover, a local Black man. Glover would ultimately become one of Lee’s first students and go on to start his own martial arts practice—also in Seattle. Lee later started a martial arts academy in Oakland.

Legend has it that Lee was ostracized within the local martial arts community for teaching martial arts to non-Asian students.

Even Lee’s romantic life served to openly challenge antiquated and toxic racial paradigms. His marriage to Linda Lee Cadwell, a white woman, in 1964, flew in the face of anti-miscegenation laws.

“Even him being married at the time was a statement on racial unity,” Hoover said.

Doug Chan, who chairs CHSA’s board, said that Lee was “pivotal in terms of capturing the popular imagination and transcending ethnic differences,” adding that Lee’s legacy continues to have an impact to this day. “He’s really become a figure for everybody.”

Mayor London Breed, who made history when she was elected as the first African American woman to lead San Francisco, seems to agree.

In a 2021 press conference in which she announced a major funding initiative for the city’s Asian American and Latin American communities, Breed praised Lee’s ability to bring people together across color lines.

“You watch Bruce Lee on TV as a kid, and everybody thought they were Bruce Lee,” the mayor said, recalling the connection she felt with the martial artists. “Not only was he on television, he was on television kicking everybody’s butt.”

District 10 Supervisor Shamann Walton, who is Black and represents Bayview-Hunters Point, also counts himself as a fan: “Everyone loves Bruce Lee,” Walton wrote in a message to The Standard. “I grew up watching all his movies. He made a huge impact in the Black community as well as across all cultures.”

A New Chapter

We Are Bruce Lee not only stands as a tribute to one of San Francisco’s most beloved sons, it also marks a new chapter for the Chinese Historical Society of America.

Located at the corner of Clay and Joice streets, the museum occupies a historic brick building that was once home to the Young Women’s Christian Association, or YWCA. CHSA has been closed to the public for the past two years, and the Bruce Lee exhibit will showcase many of the upgrades that the museum has implemented over the course of the pandemic.

These upgrades, and the show itself, were funded by a city investment in the CHSA. In total, CHSA got close to $1 million of a $4.7 million initiative aimed at revitalizing San Francisco’s Asian and Latino cultural districts.

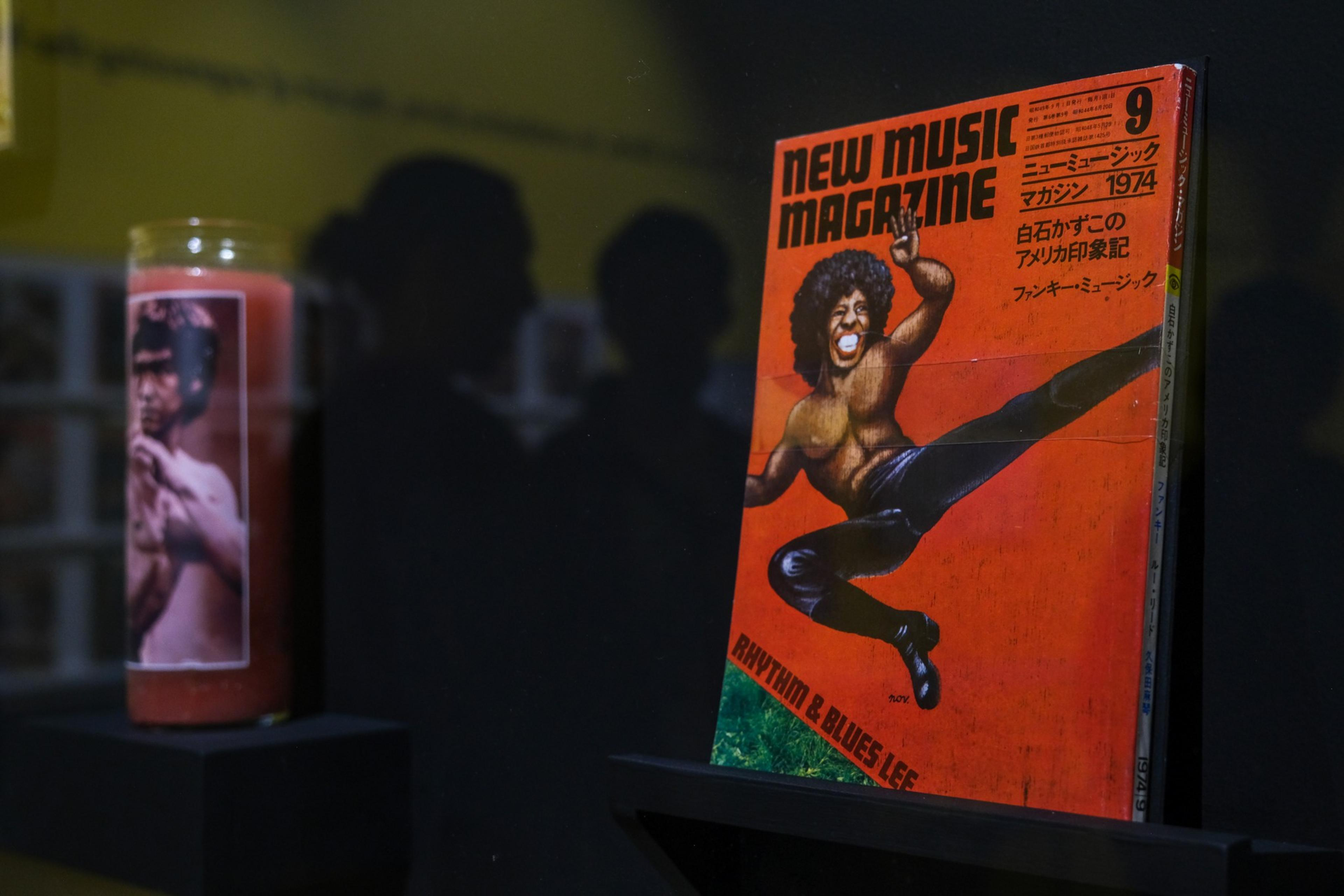

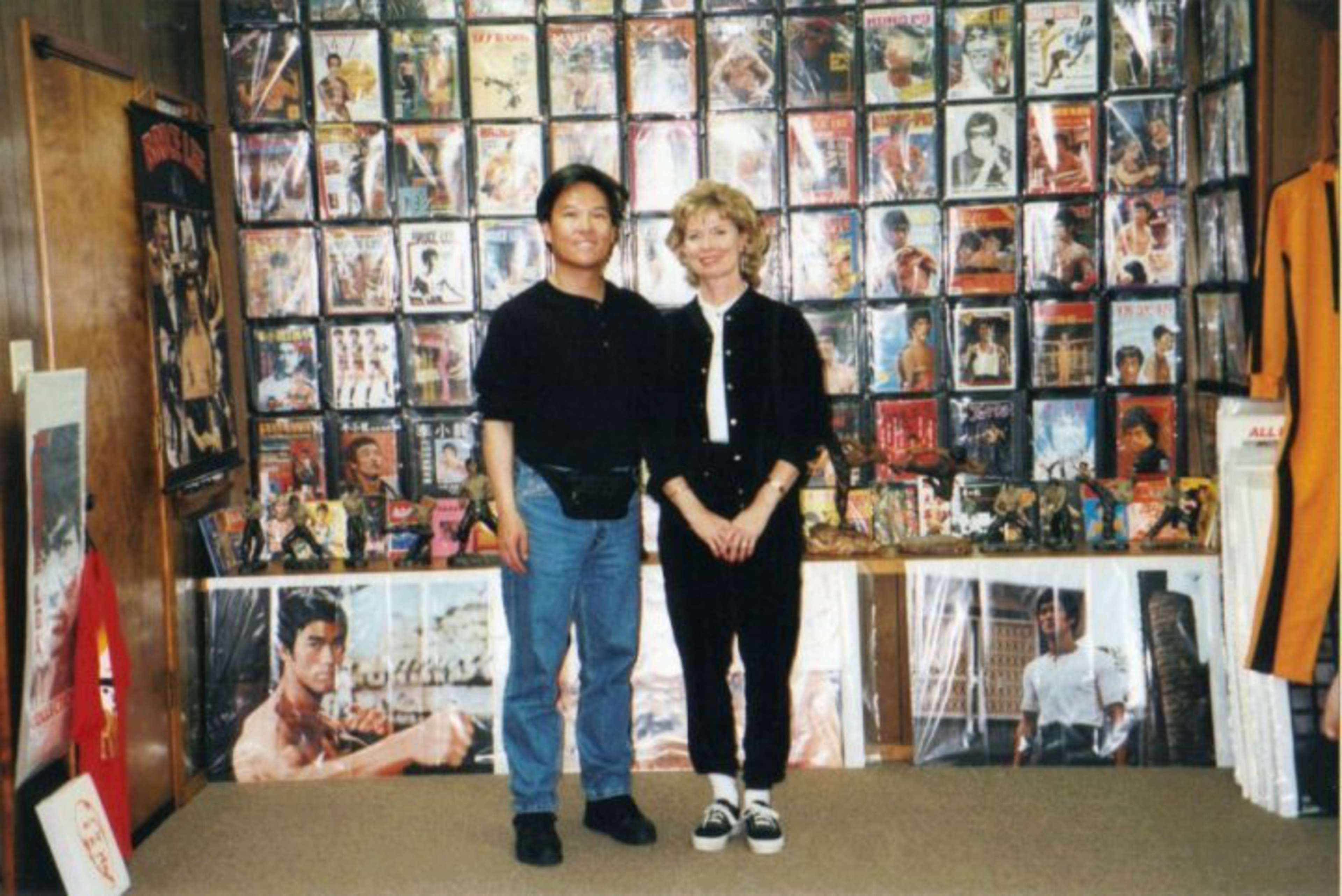

About $400,000 went toward technological upgrades and the We Are Bruce Lee exhibit, while another $600,000 is earmarked for a new welcome center, gallery and gift shop at the museum. The exhibition is also being supported by the Bruce Lee Foundation, Lee’s family members and some Bruce Lee memorabilia collectors, like Chinn, who has more than 10,000 pieces of Bruce Lee ephemera and memorabilia at his home in the Sunset District.

Looking back on Chinn’s childhood is the key to understanding why he has invested so much of his life and money in Lee’s legacy.

Chinn, a San Francisco native, was born in Chinese Hospital in Chinatown, just like Lee. Growing up in the 1960s, Chinn said racist depictions of Asians were common on TV, in the movies and even in children’s cartoons. Lee’s starpower wasn’t a panacea, but it definitely made an impact on the way Chinn thought about himself.

“Before I knew about Bruce Lee, I was ashamed to tell my classmates the hospital where I was born,” Chinn said. But after learning that he and Lee were both born at Chinese Hospital, he was proud to say he was too. “I went back to school and I bragged to all my friends: ‘Guess where I was born?’”

‘We Are Bruce Lee’

Chinese Historical Society of America, 965 Clay St.

Ongoing

Wednesdays to Sundays, 11 a.m.- 4 p.m. | $10-$15; Free for CHSA members