From Ansel Adams founding the first fine art photography department at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1945 to Eadweard Muybridge creating the first motion pictures at Stanford, the Bay Area has long been a hub of photographic history. This rich legacy is still being carried forward by a vanguard of contemporary photographers, working across styles and techniques.

Here are three galleries you can visit this week to explore works by some of the Bay Area’s best contemporary photographers.

Bill Jacobson

Into the Loving Nowhere

Catherine Clark Gallery, 248 Utah St.

Thru Oct. 22 | Free

Bill Jacobson’s diffuse photographs encapsulate a sense of estrangement and distance, of being on the outside looking in. This correlates to the artist’s experience living through the HIV/AIDS crisis, one he articulates with the simple, formal trick of taking his photographs out of focus. They don’t convey an image so much as a feeling.

“Into the Loving Nowhere,” an exhibition of his pictures from the mid-’90s and early 2000s, is as spare as its contents, featuring just five large chromogenic prints and two smaller silver-gelatin prints. But the weight of the detachment they illustrate is all-encompassing.

The color prints are all street scenes, reduced to patches of color. In one, a person walking melts into a window pane, barely distinguishable. In another, the palette of gray and green is so muted it feels like the memory of a dream. One of the black-and-white prints, and the most moving in the whole exhibition, “Interim Couple #1098,” 1994, shows two men embracing. Their closeness seems to be what the photographer wants but can’t quite hold on to.

This feeling of detachment illustrates a world receding just out of reach, even as Jacobson repeatedly attempts to grasp it on film, approaching the powerlessness of “watching my friends become ill and die.” Looking at Jacobson’s pictures made me wonder: What is in focus? Literally nothing. And it is through that unfocused absence that Jacobson illustrates loss with such crippling clarity.

Wesaam Al-Badry

The Other Language

Jenkins Johnson Gallery, 1275 Minnesota St.

Thru Oct. 29 | Free

Many things divide us in this country, not the least of which are the ideologies of labor and citizenship. Two recent collections of images by photographer Wesaam Al-Badry’s are shown together in his first solo exhibition at Jenkins Johnson Gallery. “The Other Language,” as the show is called, juxtaposes images of migrant field workers in California’s Central Valley and residents of the Appalachian coal mining town Marianna, Pennsylvania. Here, Al-Badry seeks to overcome one of the most fundamental divisions that there is—language—by communicating in a purely visual medium.

The pictures taken in the Central Valley intimate the effects of the pandemic on the community of farm workers, almost all of whom are shown wearing masks as they pick fruit or pose in the bright sunlight. The Marianna series was made before the pandemic, and many of these shots show the wistful and weary faces of the town’s predominantly white residents, staring into the camera from couches or driveways. In both cases, it’s the eyes that hold much of the feeling, meeting our gaze through Al-Badry’s lens.

Al-Badry’s landscapes are evocative, too. One shows a roadside sign in Marianna showing Donald Trump’s face imposed on Rambo’s body (Al-Badry has cleverly composed the shot so that a dinosaur mask, discarded nearby, appears to be on the verge of biting off Trump’s head). Another displays a “Farmworker Memorial” in the middle of an agricultural field, adorned with several roses and votives.

“The Other Language” offers a window into two sides of American labor. But the emphasis is always on the people that constitute those communities. In fact, the humanization of his subjects is Al-Badry’s great journalistic feat, enabling them to speak to us from within the photograph.

Trina Michelle Robinson

Excavation: Past, Present and Future

Museum of the African Diaspora, 685 Mission St.

Thru Dec. 11 | Free-$12

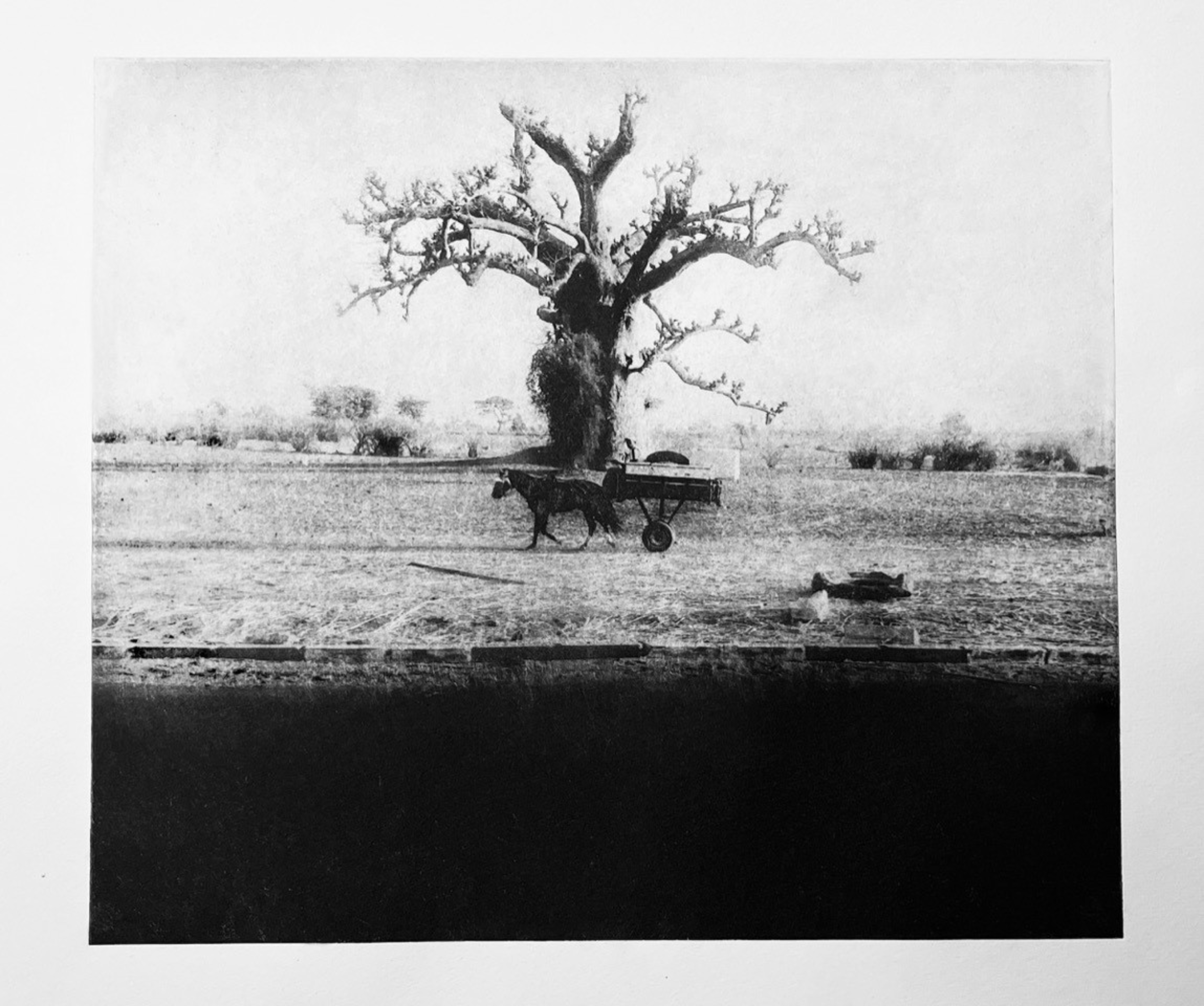

When Trina Michell Robinson discovered a forgotten family photo album in her mother’s basement, it set her on a path of self-discovery. In addition to pictures, the album contained newspaper clippings from the 1930s, which enabled the artist to trace her family’s migration to Chicago from Kentucky in the 1860s. She hadn’t thought it was possible to go back this far—and then she went further, following her lineage through the slave trade to Senegal, a research process that “changed my life because it gave me a sense of identity.”

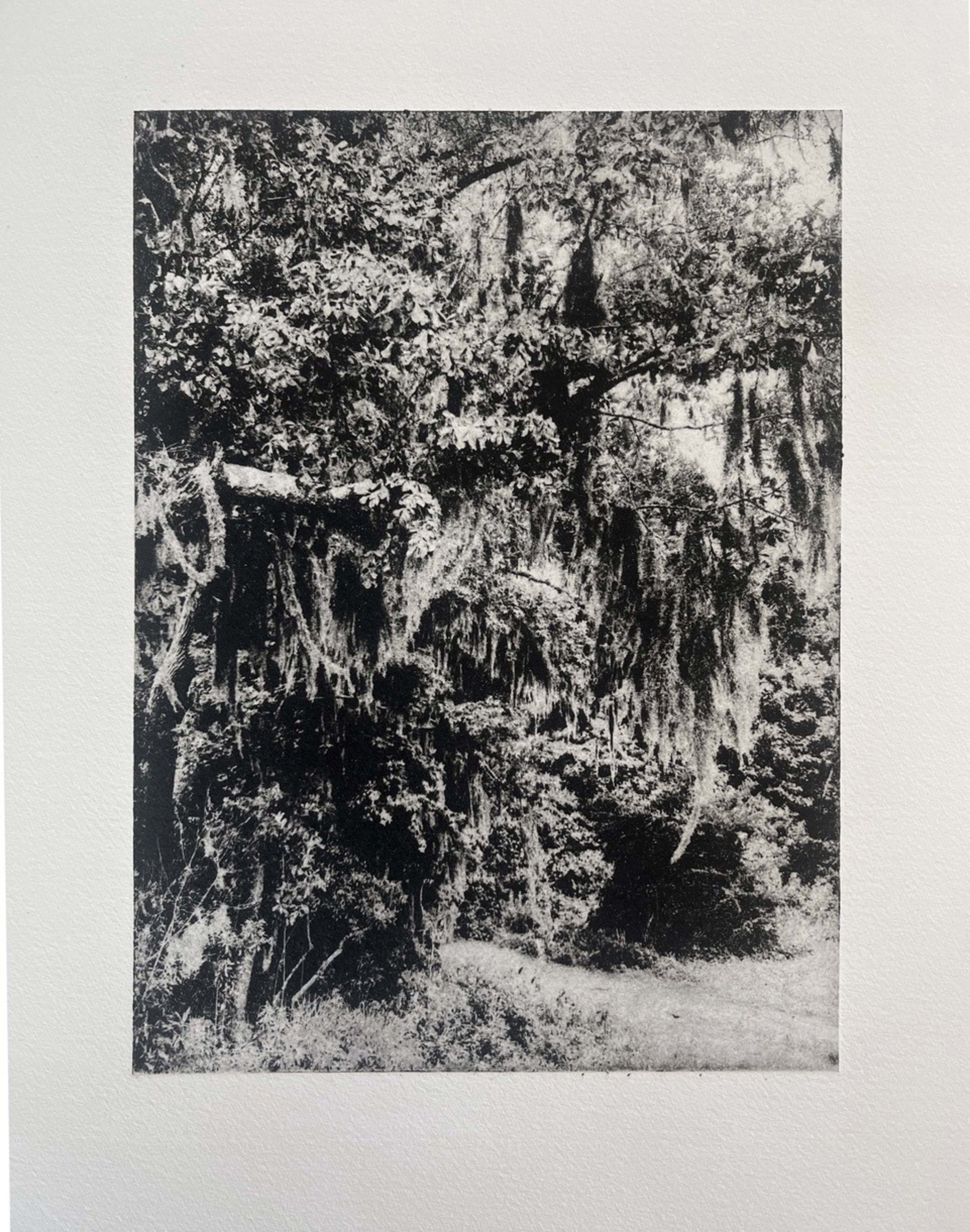

Her solo exhibition, “Excavation: Past, Present and Future,” at the Museum of the African Diaspora, pays tribute to her ancestors in a series of photographs and short films that recapture the places in Africa and the United States where they came before her. Robinson’s compositions of trees and waterways carefully exclude any signifier of the modern day, and the prints here have been made using the intaglio method, lending them a rich, charcoal-like quality that deepens this sense of timelessness.

The videos of houses and streams—all brief—are accompanied by snippets of songs, making them feel like flashes of memory, rather than complete narratives. The longest video, “Elegy for Nancy,” 2022, splices new and archival footage of the Sacramento, Ogun and Ohio rivers, the last of which being the once-border between freedom and slavery in the United States.

“Elegy for Nancy” is accompanied by a sculptural altar including wood from West and Central Africa, cotton from a Black-owned farm in North Carolina, water collected from the Ohio River, and more objects, tracing Robinson’s own journey. These physical elements remind that the story Robinson is telling isn’t totally immaterial, but rather a forgotten history that she’s in the process of excavating by any means necessary.