The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency will vote next Tuesday, Dec. 6, on whether to make 15 thoroughfares in its Slow Streets program (opens in new tab) permanent. That program, born out of the pandemic as a way to give residents more socially distant ways to get outside, has created a loose network of streets that reduce vehicular traffic while giving back asphalt to pedestrians, cyclists, skaters and others.

Some transit advocates have long felt the program doesn’t go far enough, hoping to create a true, interconnected network across San Francisco that would enable people to get virtually anywhere without worrying that they might become the city’s next pedestrian fatality. To that end, they’ve released an alternative, called “The People’s Slow Streets (opens in new tab).”

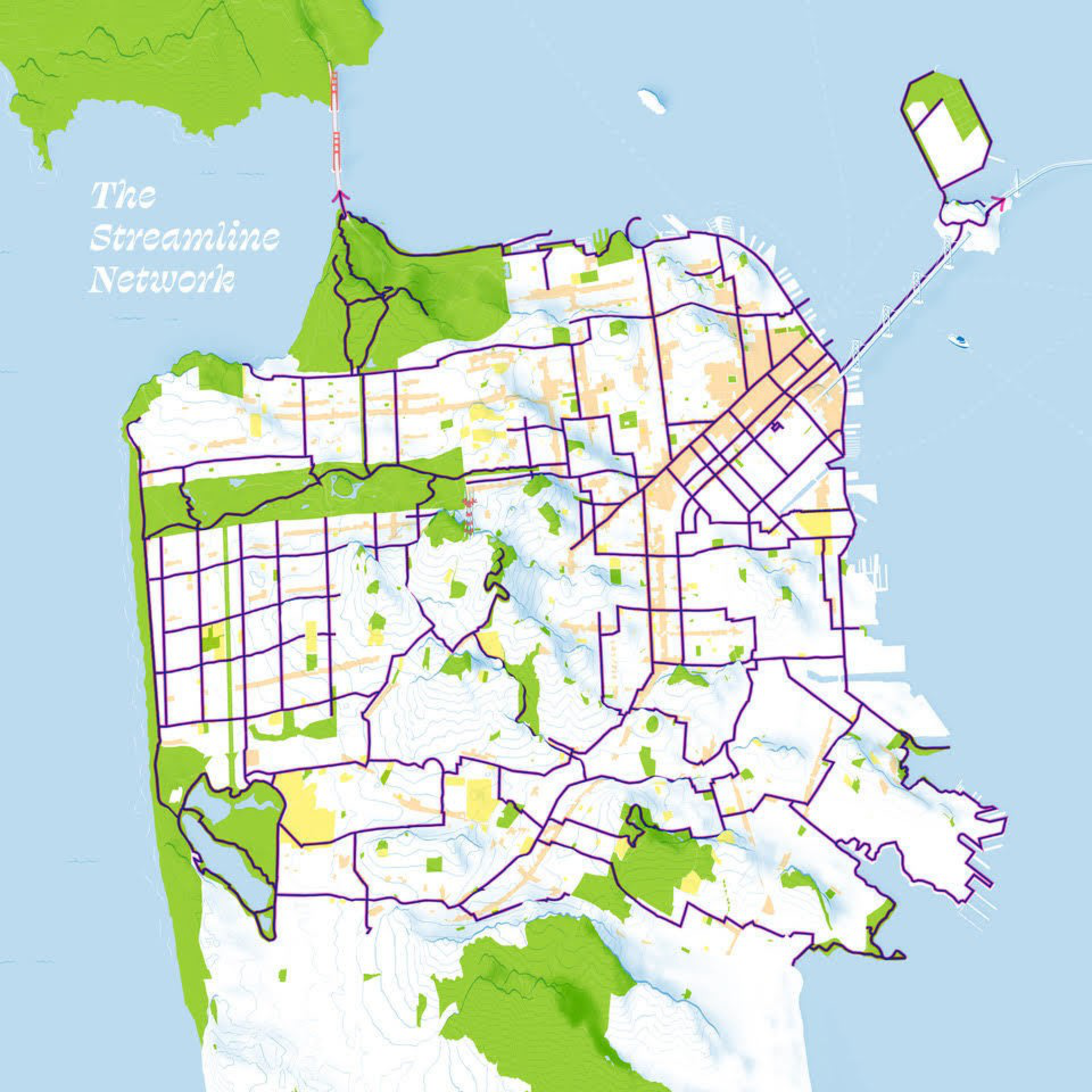

It’s an ambitious proposal, roughly doubling the total length of all existing Slow Streets (opens in new tab), to 100 miles in all. The plan encompasses roadways with considerable bike infrastructure already (such as Folsom Street in SoMa) to streets without it (Cortland Avenue in Bernal Heights) to more outlying streets that had been proposed as Slow Streets but never quite made it (Cayuga Avenue in the Outer Mission).

Virtually the entire bayfront from Candlestick Point to the Golden Gate Bridge would be protected. So would transit advocates’ ultimate white whale: the Bay Bridge’s Western Span, which would be adapted to include other transit uses as the Eastern Span has, not closed to cars entirely.

All of this is necessary because the current program will end 120 days after Mayor London Breed rescinds the Covid emergency declaration, which will happen eventually. Further, the existing Slow Streets are scattered and sometimes poorly signed, confusing drivers and pedestrians alike.

They end “sometimes end suddenly and fearfully,” according to Luke Spray, an associate director at the San Francisco Parks Alliance. “So we put this plan together mainly to say this should be a program that functions well and connects every neighborhood in the city, to make it easy for everyone to get where they need to go.”

“Taking away any one of these streets compromises the entire network,” Spray added.

The coalition supporting The People’s Slow Streets includes organizations such as Walk SF and the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, but also groups that Spray describes as “maybe a little less vigorous” in calling for tweaks to the cityscape, such as the African American Arts and Cultural District or Senior and Disability Action.

“The fear is SFMTA approving theirs, and going no further with it,” Spray added.

Since its inception in 2020, Slow Streets has met with mixed results. Some, such as Page Street in the Lower Haight, are widely considered to be successes. Others, like Lake Street in the Richmond, remain controversial in spite of strong use, while Shotwell Street in the Mission is popular in spite of minimal reductions in traffic.

However, evidence suggests there is an appetite for safer streets. In passing Proposition J earlier this month, San Francisco voters enshrined car-free JFK Drive in Golden Gate Park by a 63-37 margin. Further, the city’s own Vision Zero goals mandate the elimination of pedestrian fatalities by 2024, an increasingly ambitious goal that The People’s Slow Streets’ own timeline coincides with.

“That’s the thing that Slow Streets shows: It doesn’t have to take awhile,” Spray said. “We included a way to have community progress, but not take a thousand years.”

Installing bulbouts and other traffic-calming measures may seem like a universal good, but equity is a major concern. It’s easy to redirect car traffic from a wide, residential street in an upper-middle class area with good transit—Sanchez Street in Noe Valley, say—but less-served, lower-income neighborhoods whose inhabitants endure truck traffic may see things differently.

Indeed, when SFMTA initially proposed the Slow Streets, residents of the Bayview observed that they hadn’t even received crosswalks. So The People’s Slow Streets calls for $10 million in equity investments for communities that require even more safety infrastructure.

Spray applauds SFMTA for keeping Slow Streets flexible and incorporating community feedback on things like making barricades more permanent. The People’s Slow Streets would build on that, while making it clearer to all road users what Slow Streets are.

“We want car-free spaces that prioritize people, and the next step with that is Slow Streets,” he added. “They don’t take away parking or hinder deliveries or day care access. They just make sure residential streets stay residential.”