The interior courtyard of San Quentin State Prison has the feel of a well-manicured college campus. Hydrangeas bloom in shades of purple and blue, a sprinkler waters neatly trimmed grass, buildings house a variety of amenities from religious centers to computer coding classes.

Yet it only takes a glance up to the barbed wire-topped fences or the Medieval-looking “Adjustment Center” to remember where you are: a maximum-security state prison.

The facility has its inconsistencies—and so does Gov. Gavin Newsom’s vision to transform (opens in new tab) the infamous prison into a model rehabilitation and educational center in just two years.

Since Newsom’s March announcement of his ambitious plan (opens in new tab)—which includes the construction of an educational center in a warehouse where inmates used to make furniture—he has appointed a 17-member council that has met three times and secured $380 million in funding for the project (opens in new tab).

Yet the council, tasked with producing a report in December, lacks any members with building or facilities experience.

When asked specifics about how construction would take place in such a short time frame in a field known for a byzantine system of permitting, Warden Ron Broomfield demurred, claiming he wasn’t the expert on that particular aspect.

“Everyone wants to talk about the building, but it’s only one component of the plan,” he said, noting that the re-entry process and staff experience have also been identified as critical needs.

Yet it’s certain to be the most visible component, and it’s necessary for programs to succeed.

Much of the expansive array of programming at San Quentin has a significant waitlist—all due to space limitations. Mount Tamalpais College, the only college degree-granting program inside prison walls, has a waitlist of 250 students, according to the school’s development director, Makenzie Means.

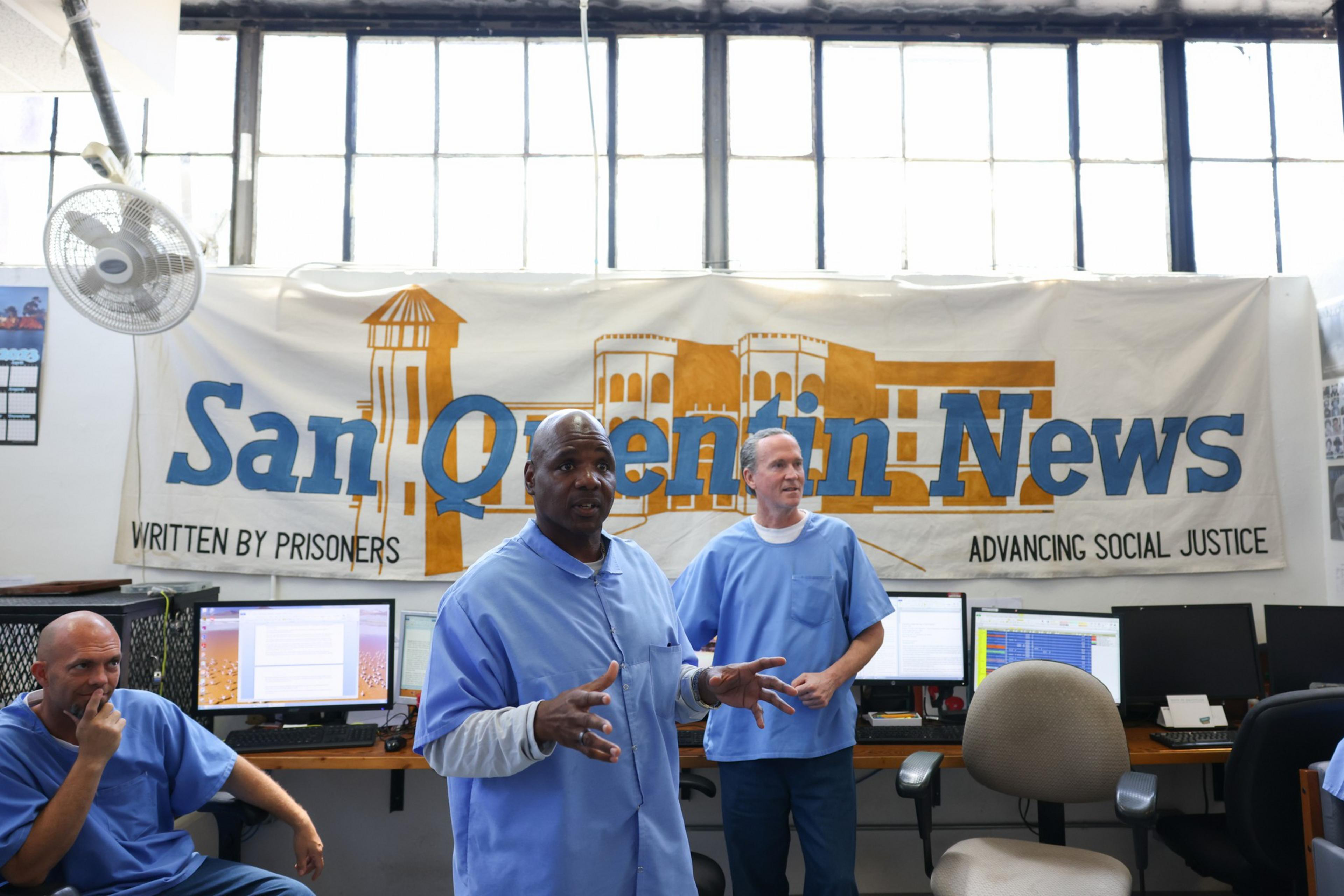

In many ways, San Quentin is already a model of prison reform, offering everything from college courses to a running club, with an inmate-run newspaper and media center. The expansive array of options leads inmates, who number around 3,000, to request transfers to the prison, only to find the programs they were in search of aren’t available.

“It’s a bit like going to Disneyland and not being able to go on any of the rides you want because the lines are too long,” Broomfield said.

The panoply of programming also begs the question why the state would begin with San Quentin when it has more than 30 other prisons facing a dearth of programs.

“There has to be a model to point to,” said Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg, who leads the advisory council. “Once there’s a successful model, it’s up to the state and legislature to point to what’s possible.”

These programs have worked: the San Quentin News staff boasts a 0% recidivism rate since 2008 (opens in new tab). That statistic is posted above the entry to its newsroom, with monthly issues of the gazette pinned proudly to the wall behind protective plastic. The computer coding program (opens in new tab), run in partnership with the California Prison Industry Authority, has had graduates hired by Mark Zuckerberg and also boasts a 0% recidivism rate.

Many of the successful rehabilitative programs inside San Quentin are volunteer-run and are funded by philanthropy and grants, not the government. Of the more than $14 billion annual budget of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation—what some have called a “money pit” (opens in new tab)—only a fraction is dedicated to the “rehabilitation” component that’s in its name.

“Most of the progress is being made by the program providers who are bringing in these innovative programs,” said James Fox, who founded the Prison Yoga Project that offers classes in San Quentin. “We spend more time trying to deal with the system itself than we do delivering the programs.”

That means a massive culture shift will need to take place alongside the construction of a facility—one that reimagines the relationship between inmates and staff.

“We need to get correctional staff involved in rehabilitation,” Broomfield said, “so they can be the influence that changes a person’s life.”

Yet such a reorientation would face steep odds, such that it could hardly be achieved with a 24-month effort. The toxic levels of stress associated with the profession can create symptoms similar to that of PTSD. Correctional officers have a suicide rate 39% higher (opens in new tab) than the national average, as well as shorter life spans.

The average life expectancy for a prison guard is 59 years old while the national average is 75 (opens in new tab). An entrenched system that prioritizes punishment over rehabilitation means that change can only happen slowly.

“Everybody isn’t on the same page when it comes to focusing on the importance of rehabilitation,” Fox said. “That’s the bottom line.”