Whipped and battered by the wind, the giant rainbow flag that flies above San Francisco’s Castro District gets replaced from time to time. On Friday morning, the Castro Merchants Association held a small ceremony at Harvey Milk Plaza to lower the slightly weather-damaged colors and hoist a spiffy replacement.

“Every flag costs about $1,200,” Terry Asten Bennett, president of the Castro Merchants, told The Standard. “We have to change it every three to four months. It is a labor of love, but it’s so important to the community.”

Reinstalling it requires about a dozen people. Asten Bennett dedicated Friday’s ceremony to the passing of Sen. Dianne Feinstein—who became mayor of San Francisco after the November 1978 assassinations of Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone. Notably, it took place two days before the 49th annual Castro Street Fair (opens in new tab), which Milk founded, when the somewhat beleaguered neighborhood gets to show off its best side to the city.

“The flag remains a symbol of hope and offers a message of welcome to all who come to the Castro,” the fair’s Executive Director Fred Lopez told The Standard.

The 20-by-30-foot flag is indeed an 18-pound beacon of love and tolerance, but the Castro’s rainbow flag has also been a focal point of community infighting ever since it was first raised in the early 1990s.

A little background: Although the six-colored rainbow flag seems like an almost eternal emblem of LGBTQ+ pride and visibility, the Pink Triangle, once pinned to gay men in Nazi concentration camps and later reclaimed, is arguably the original icon of the modern fight for liberation. The rainbow flag was created in San Francisco in 1978 by artist Gilbert Baker, who went on to make humongous versions, up to a mile long, that were paraded near the United Nations and in Key West.

The rainbow flag originally had eight colors, each symbolizing a facet of queer life, but the hot pink and turquoise stripes were later removed because obtaining those fabrics turned out to be too expensive (opens in new tab). Now, virtually every community under the LGBTQ+ umbrella has its own version (opens in new tab), from the pastel transgender flag and the earth-toned bear flag to the less-seen demisexual flag.

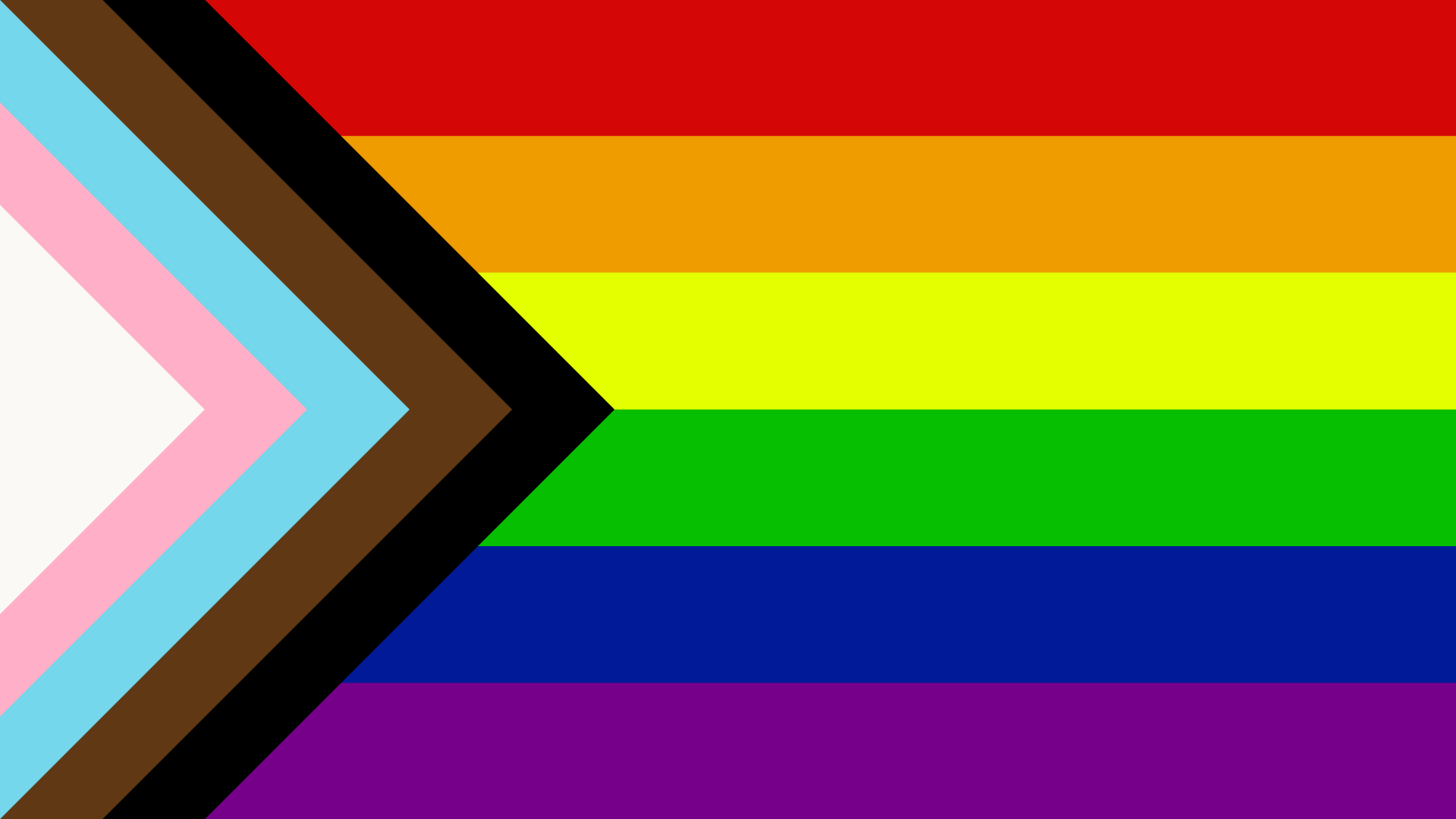

Having become all but ubiquitous every June, the flag has arguably never been more controversial—and not just among conservative legislators or at Target. To some younger queer activists, the standard rainbow flag has come to feel commercialized and a bit dated (opens in new tab), a vaguely exclusionary totem from the era when the San Francisco LGBTQ+ Pride Parade was simply known as Gay Freedom Day. The two alternatives that have come to supersede it are the Philadelphia Flag and the Progress Flag, each of which adds design elements that are meant to include gender-variant people and people of color.

In 2021, the Castro LGBTQ+ Cultural District circulated a survey meant to assess the community’s interest in replacing the neighborhood’s enormous flag with one of those newer designs. Nothing seemed to come of it (opens in new tab), and the cultural district takes no official position on the matter.

Nonetheless, passions run hot. In 2022, a flyer went around the neighborhood during Pride month, slamming the possibility of replacing the flag without adequate community input (opens in new tab) and asserting that someone, somewhere, was making money off it. Some people contended that the rainbow flag was inherently inclusive enough, thank you very much. Others groused that the black stripe symbolized people who had died from HIV/AIDS, crowding out the contributions of Black people to the LGBTQ+ liberation movement.

It is true that the Progress Flag was created in 2018 by artist Daniel Quasar, who describes themself as a “queer nonbinary celestial object having a human experience.” But the belief that they demand payment in exchange is inaccurate (opens in new tab): They explicitly allow free use, and only request compensation from corporations and large manufacturers.

At the same time, replacing the Castro flag isn’t so simple, as it’s technically not a civic monument but an art installation that must fly at full-mast, with the Castro Merchants as its steward.

“Baker was very smart about doing this,” local LGBTQ+ advocate Stephen Torres told The Standard. “He raised the funding for it as an art piece. It has to remain the same in its current installation. Removing it would be like taking down any other piece of art.”

Of course, other designs have temporarily flown on that pole, like the black-white-and-blue-striped Leather Pride flag, with its recognizable red heart. That, too, led to hurt feelings and accusations of favoritism, so the Castro Merchants has since restricted it to Baker’s design. The Leather and LGBTQ+ Cultural District in western SoMa later installed a giant Leather flag of its own at Eagle Plaza (opens in new tab), clearly visible from the Central Freeway.

Replacing a large flag several times a year for 30 years means quite a pile of cloth accumulating in a storage unit. As the Castro gears up for Sunday’s street fair, the merchants group is set to announce a program where museums, schools and other organizations can obtain a piece of LGBTQ+ history, for nothing more than the cost of shipping.

Still, for all the infighting and tempests in a teapot, the flag remains an undeniable presence above the world’s most famous gayborhood, a potent visual opposite the Castro Theatre’s neon blade. Even at the busy intersection of Castro, 17th and Market streets, its billowing is distinctly audible, drawing onlookers to stare upward and reflect that progress is hard-won and perhaps quite fragile.