San Francisco is no stranger to panda-mania.

The City by the Bay went ape for two giant pandas shown at the San Francisco Zoo for three months in 1984.

About 43,000 visitors braved rainy weather and a two-hour-long wait in the first nine days for the chance to take a peek at the visitors from the Peking Zoo, according to press reports from the time.

RELATED: A Panda for San Francisco Zoo? Mayor Breed Is Asking China

All told, the black-and-white bundles of fun brought a record-setting 409,000 visitors to the zoo and ended then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein’s three-year quest to arrange a panda visit.

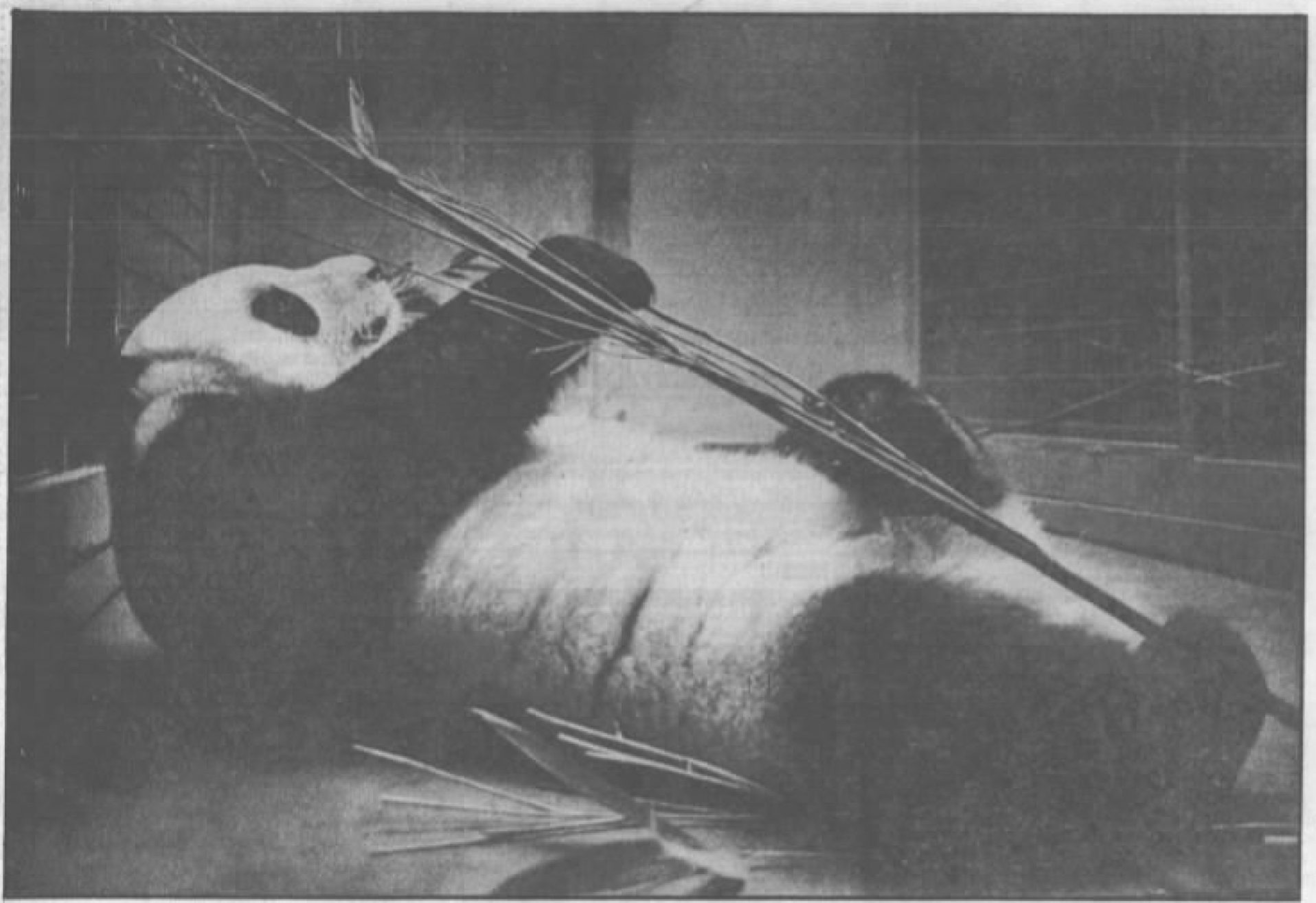

Wild-born Yun Yun and Ying Xin, both 3 years old, were lent to the Los Angeles Zoo by China for a 3½-month stay during the summer of 1984, when the city hosted the Olympic Games. Afterward, they made a stop in San Francisco.

On top of bamboo, zookeepers fed the the still-growing duo eggs, apples, ground meat, beef bones and yogurt. And thousands of visitors lined up to see them roughhouse and roll around everyday.

Then endangered, giant pandas were lent out for a fee to raise money for the species’ preservation; the animals’ numbers had fallen to 1,000 due to a bamboo famine in their mountain habitat that had caused them to starve. China has been recalling the animals from U.S. zoos, but President Xi Jinping hinted at their return during APEC in November.

But the San Francisco Zoo played an even earlier role in the “panda diplomacy”—whereby China leased pandas to other countries as a goodwill gesture—that began with President Richard Nixon’s trip to Beijing in 1972. That visit ended 25 years of isolation between the United States and the Communist-led country and led to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries in 1979.

Nixon presented two musk oxen from San Francisco Zoo as a part of a gift to China. The country’s leader, Zhou Enlai, reciprocated by providing two giant pandas as a “gift of appreciation,” Nixon said. The pair—Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing—were put on display in Washington, D.C.

San Francisco’s panda-loving public made the brief visit from Nov. 2 to Jan. 24 count, obliterating attendance numbers at the zoo and raising funding for the endangered animals. Feinstein encouraged zoo visitors to contribute at least 25 cents to a city-sponsored “Save the Panda” fund. The San Francisco Examiner devoted a page to publishing panda-themed poetry written by Bay Area children.

But in fact, San Francisco had seen a giant panda once before—in 1936.

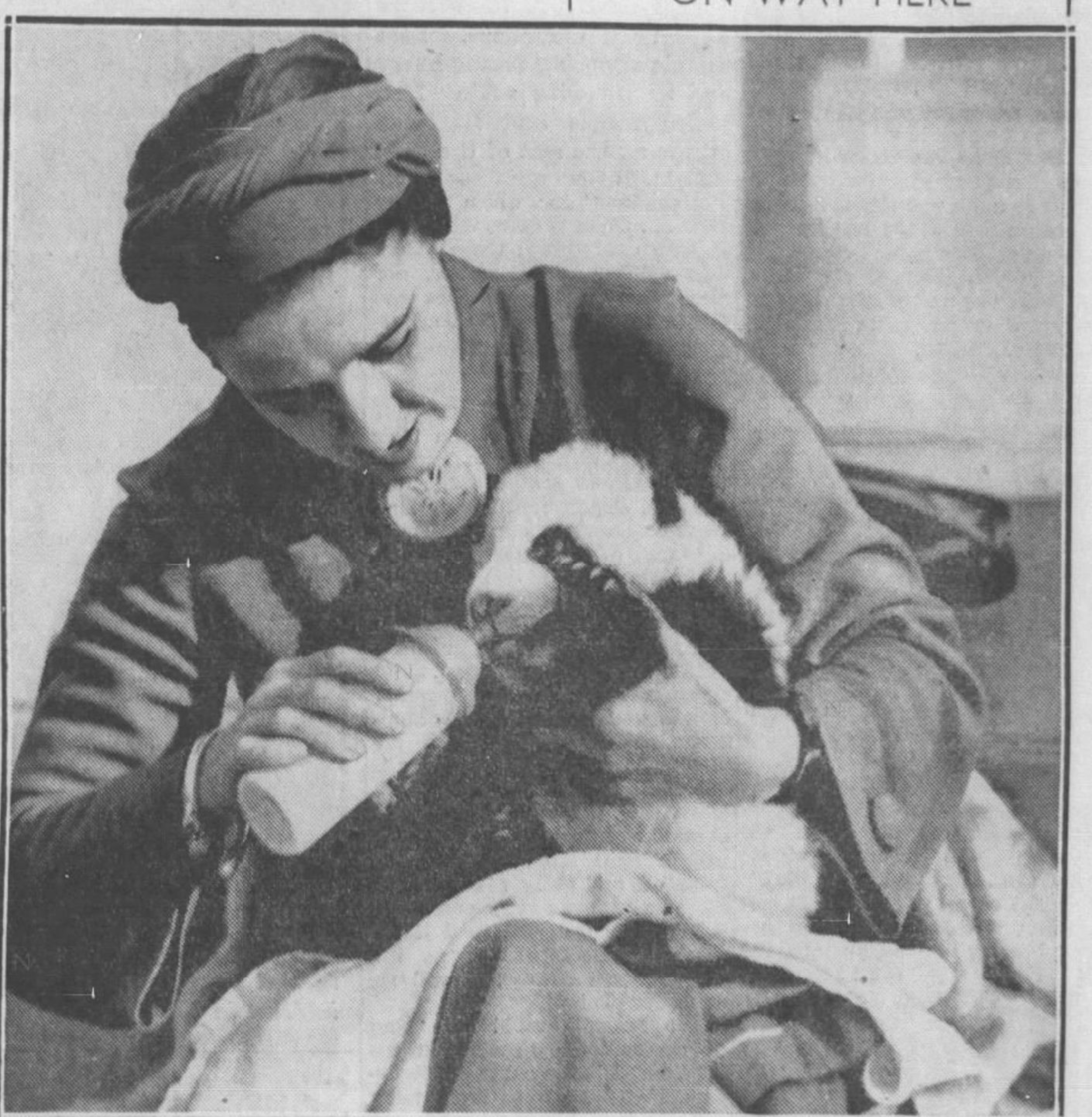

That year, an adventurous socialite, Ruth Harkness, returned from China carrying Su Lin, a 3-month-old giant panda. Dozens of print reporters, camera operators and sound-reel technicians boarded the S.S. President McKinley to interview her.

Harkness had captured Su Lin along the Tibet-Sichuan border six weeks earlier. Her husband, William Harvest Harkness Jr., an heir to the Standard Oil fortune, had died during an expedition in the same area, according to an account in the Examiner.

She later wrote a book about her adventures in China in a book called The Baby Giant Panda that recounted the day.

“Su Lin had been photographed before but never by such a complete battery of cameras,” Harkness wrote. “Dozens of flashlights exploded in a glare. She couldn’t have two sips of milk in peace.”

The Brookfield Zoo near Chicago purchased Su Lin, who was actually a male. But the 2-year-old panda died of pneumonia in 1938. His preserved body was put on display (opens in new tab) at the Field Museum of Natural History. Harkness obtained other pandas for the zoo.

While San Francisco’s latest appeal to get giant pandas is in play, you can still satisfy your panda fix. San Francisco Zoo is home to red pandas (opens in new tab), but those are more closely related to raccoons than giant pandas.