Shannon Sweeney slipped on a pair of black latex gloves and tore open the trash bag sitting on a 47th Avenue sidewalk.

“Bingo,” she said, pulling out a document listing the address of the home just feet from the pile of broken furniture, cassette tapes and garbage bags clogging the public walkway. Mail, shipping labels and bills are gold for Sweeney: They provide the identifying information she needs to crack down on whoever’s waste is sullying city streets.

Sweeney is one of San Francisco’s illegal dumping investigators. While her technical title is less dramatic—Department of Public Works outreach coordinator—Sweeney’s day-to-day job is a mix between debris detective and social worker. The 23-year-old patrols the Richmond, tasked with cutting down on the amount of refuse that lands on the neighborhood’s streets and sidewalks.

On a recent Thursday, Sweeney did her rounds wearing white Adidas Sambas, which she prefers over her department-issued steel-toe boots, and driving a city-owned minivan that has seen better days. Her fanny pack was filled with masks, hand sanitizer, sunscreen and lots of gloves, which she keeps in designated dirty and clean pockets. Her main tool is a tablet computer, which she uses to check up on the dumping history of wrongdoers she identifies, photograph trash for evidence and file work orders for the city cleanup crews who follow behind her.

Her preference is to talk first when she can, perhaps educating a new business that no, you can’t just plop your garbage next to the city bin to get picked up. But she’s also not afraid to issue citations, which can climb to $1,000 a pop, to repeat offenders who refuse to get the message that the sidewalk is not the place for their waste.

And waste there is aplenty. In just a few hours riding around with Sweeney, The Standard saw her tear into illegally dumped garbage bags that turned out to contain paper documents, cardboard boxes, fiberglass, drywall and even urine and feces.

“Oh, no,” Sweeney shouted when she opened a bag containing the latter. Rarely hesitant to tackle a mess, this one sent her over the edge.

“I can’t hide it on my face,” she said, grimacing and groaning as she backed away.

Trash everywhere

San Francisco has an illegal dumping problem.

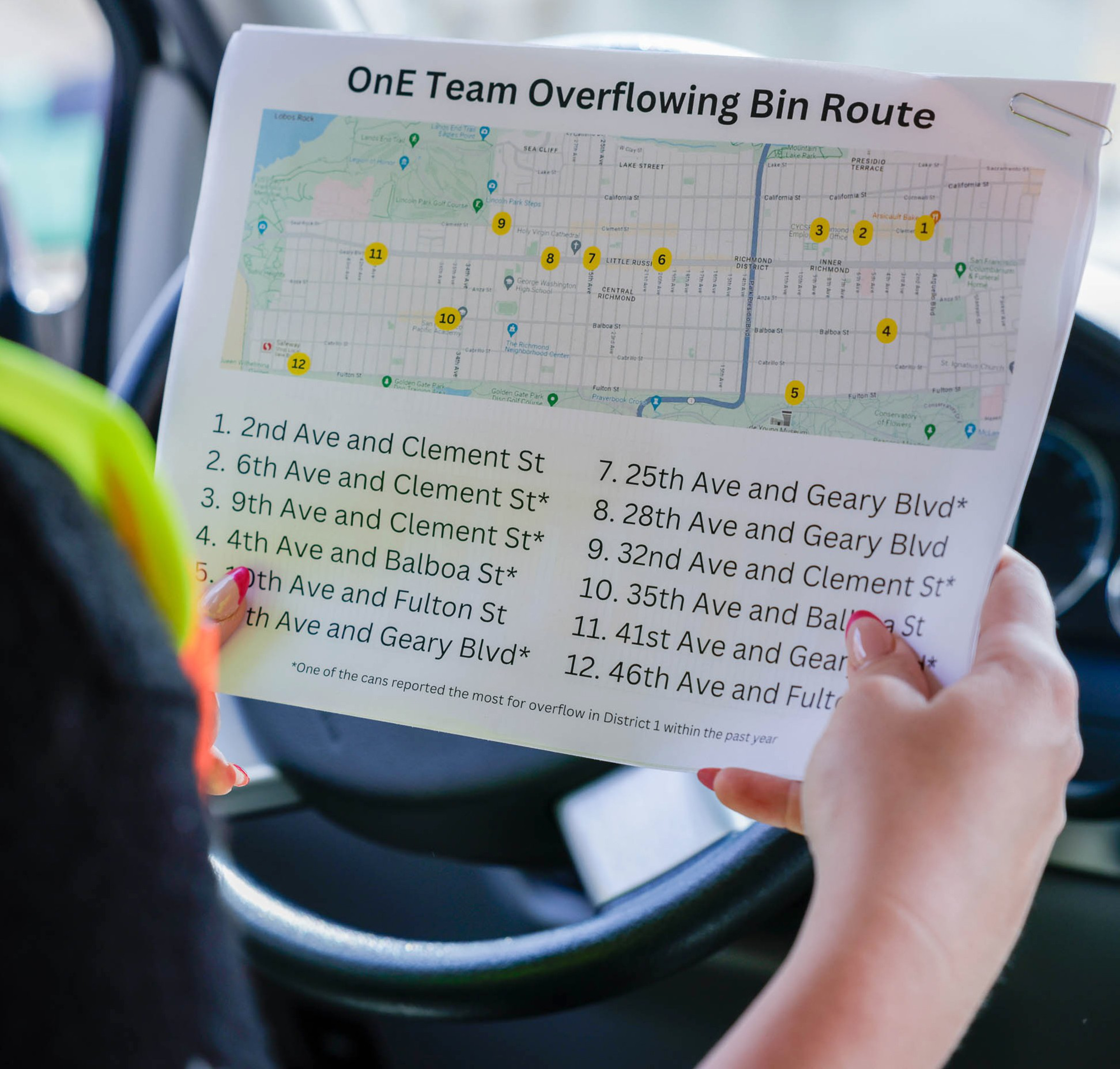

The issue is not new. But even though officials have combated it for years, city data shows that it has continued to be a bane for residents. In 2023, San Franciscans submitted an average of nearly 1,600 complaints to 311 per month reporting that public bins were overflowing, which can indicate an illegal dump near the can.

(Thousands more 311 requests can be traced back to automatic sensors that notify Recology when a bin is overflowing, according to Public Works spokesperson Rachel Gordon.)

Gallery of 8 photos

the slideshow

Anyone living in San Francisco doesn’t need data to tell them that the streets are often strewn with garbage. Just this Tuesday, Green Apple Books Manager Eileen McCormick walked up Clement Street only to find about a dozen overflowing trash bags flung in front of the store.

“It’s really frustrating to feel like someone else expects me to clean up their mess by dumping it in front of the businesses on our street,” McCormick said.

The city’s Public Works department is well aware of the issue.

“During Covid, this team got decimated,” Gordon said of the illegal dumping enforcement unit. “Everyone got deployed to Covid command.”

Last year, Ramses Alvarez, who oversees the trash investigation team, strove to get it staffed up once again. Today, the Public Works Outreach and Enforcement Team numbers six, with each member assigned their own swath of San Francisco.

“I think they’re really hitting their stride at this point,” Alvarez said.

You need to find out who’s doing it

Some of San Francisco’s illegal dumping can be traced back to ignorance, according to Sweeney.

“I noticed that following Covid, we almost had to reteach the rules,” she said. There are new businesses cropping up across the city and some see their neighbors dump trash next to the sidewalk city bin and just assume that’s OK, according to Sweeney. (To be clear, it’s not.)

That relearning of the rules may have applied to a local grocer who had left a rundown ice chest next to the business. Sweeney popped in with instructions to get it off the sidewalk. When she walked past that block again 20 minutes later, the ice chest was gone.

In other cases, landlords try to save cash by paying for Recology’s smallest bins, or no service at all, leaving tenants with few options for getting rid of their waste, according to Sweeney. That’s why part of her job is to walk the streets making sure that each address has signed up for sufficient garbage service.

But many of San Francisco’s dumpers are far less innocent and behave like seasoned scofflaws, flaunting dumping regulations without hesitation.

Alvarez recalled receiving a video from an upset resident showing their neighbor walking out of their building and flagrantly tossing bags of trash on the corner sidewalk. His team issued a $1,000 citation to the building owner, which resulted in a furious voicemail showing up in Alvarez’s inbox.

“I am not the person who dumps that out,” the person said on the voicemail. “You guys need to find out who’s doing it before you start fining people.”

City officials showed the citation recipient the video, prompting them to acknowledge that the person who dumped the trash did, indeed, live at the property, according to Public Works spokesperson Gordon. She could not verify whether or not the person shown dumping in the video was the same person who left the angry voicemail.

“It was representative of what I have to deal with,” Alvarez said. “For every person that says, ‘I didn’t do it,’ there’s some video evidence that shows you did it.”

Hasty investigation

Some San Franciscans have a dimmer view of the recently revamped Public Works illegal dumping enforcement effort.

“All they care about is $1,000 fines,” Bayview resident Richard Petersen said.

He received a notice of violation out of the blue, a warning letter stating that the city would fine him if he illegally dumped again. But Petersen, whose neighborhood is beset by the most egregious illegal dumping in San Francisco, insists that he wasn’t the culprit. He speculates that someone must have taken a piece of paper out of his recycling, eventually routing it to a public garbage heap near his home.

Petersen is all for the city cracking down on the waste that regularly shows up in his neighborhood; he just wishes the city had more proactively looked into his case by talking to him directly before issuing the warning.

“I think it was appalling that they would send this letter without any investigation whatsoever,” Petersen said.

After making a stink, Petersen got a reply from the city that it would rescind his notice of violation.

Tenderloin Housing Clinic Director of Housing Services Marilyn Mendoza, however, says the city has been unresponsive to her pleas to repair or move a public bin outside her office that has become a magnet for illegal dumping.

When the bin is overflowing or not functioning, people just start tossing waste beside it, according to Mendoza. That’s left clients visiting her office in wheelchairs to navigate around piles of junk just to get inside. Despite repeatedly filing 311 reports, which the city typically responds to within four to six hours, the dumping has continued.

She wishes someone from the city would proactively reach out to her organization and others in the Tenderloin to help address dumping hot spots.

“I don’t think, from my standpoint, that they’re doing enough,” Mendoza said.

While Alvarez is proud of his crew’s work, he recognizes that they’re fighting a never-ending battle. At the core of the problem, according to Alvarez, is that many city residents have lost the sense of pride and ownership over the space in front of their homes that people in his grandparent’s generation had.

If he could wave a magic wand to fix the problem, he would use it to return the sense of responsibility he thinks has eroded.

“Because ultimately we could clean all day with the staff that we have,” Alvarez said. “But if there’s constant illegal dumping, if people are going to abuse the city trash cans, the city’s never going to get clean.”