The city’s Biking and Rolling Plan is in the midst of a dreadful summer tour.

The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency has hosted open houses across the city over the past five weeks in its effort to create a citywide connected network of bike infrastructure. The response will be familiar to anyone acquainted with SF’s biking politics: merchants raised red flags (opens in new tab), community advocates threw up resistance (opens in new tab) and politicians heartily disapproved (opens in new tab). Even some bicycle activists, the people who should have the most to gain, are frustrated (opens in new tab) by the whole process.

So what exactly is in this plan that’s become the hottest thing to hate in San Francisco? Nothing. The biggest open secret in SF transportation policy is this: Two years since the project launched, the Biking and Rolling Plan (opens in new tab) still doesn’t exist.

“We spend years talking about it, and then talking about it again, and then doing some more outreach, and then doing a new plan,” said transportation advocate Luke Bornheimer. “This is just classic San Francisco.”

Already more than a year behind schedule, SFMTA will present a plan, for real, in early 2025, according to an agency official.

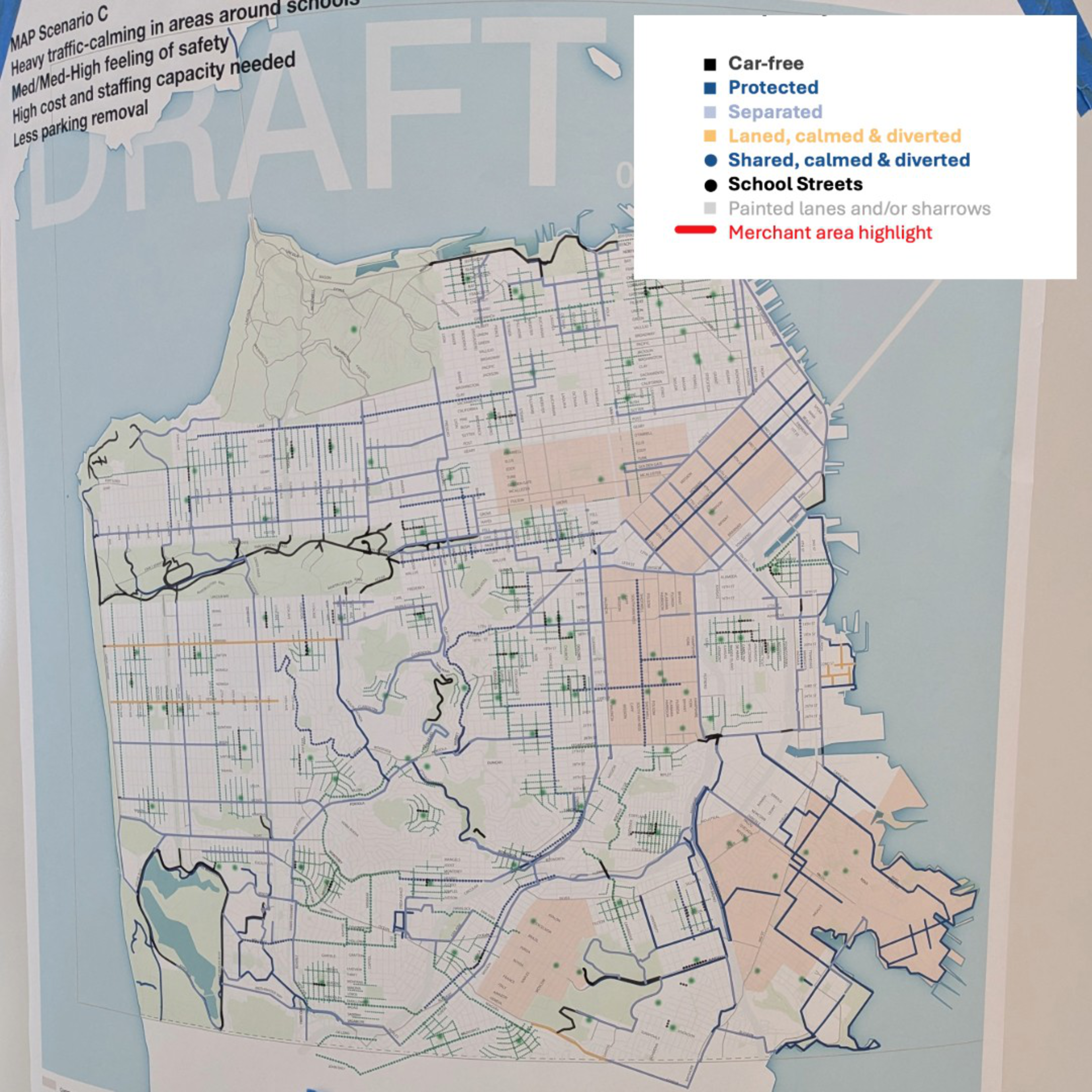

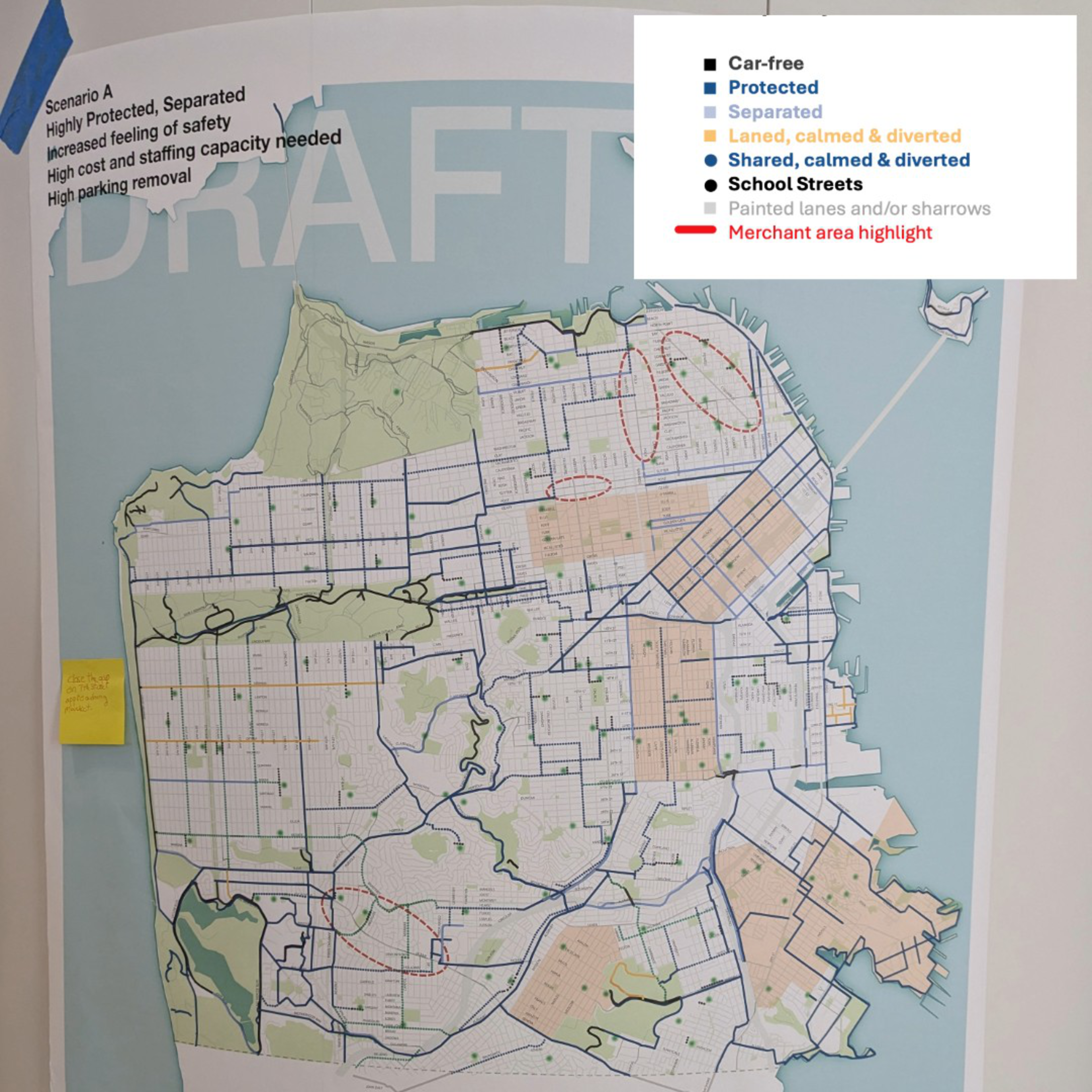

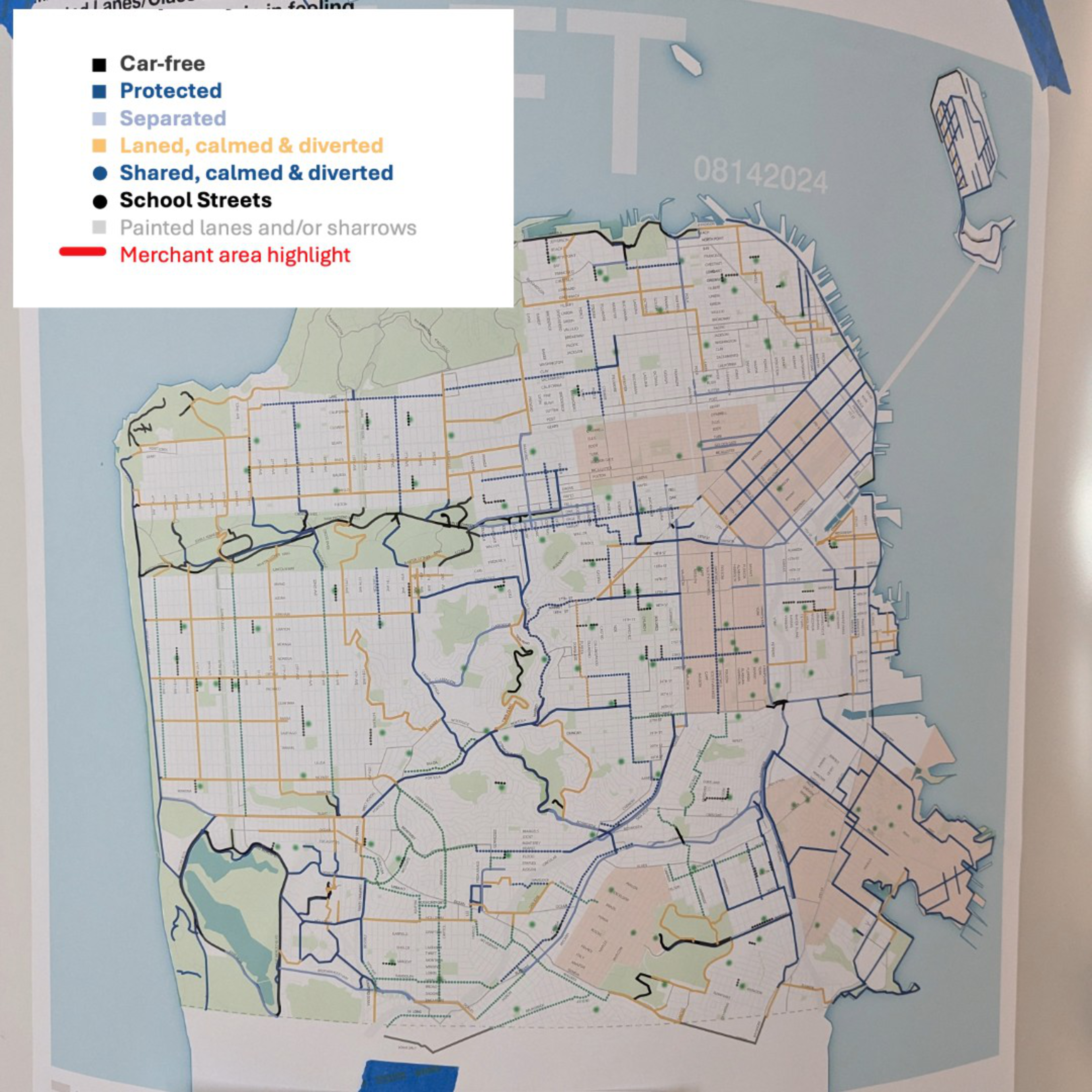

In the meantime, the most specific information the SFMTA has released is a series of three “scenario” maps outlining different visions of how the city’s bike infrastructure could change under its final proposal. They show how the city might, or might not, one day be crisscrossed with far more bike lanes, slow streets and school zones. But when The Standard requested digital versions of the maps, the agency refused. A spokesperson explained that the SFMTA doesn’t have anything up-to-date enough to share, since the maps have “been under constant revision.”

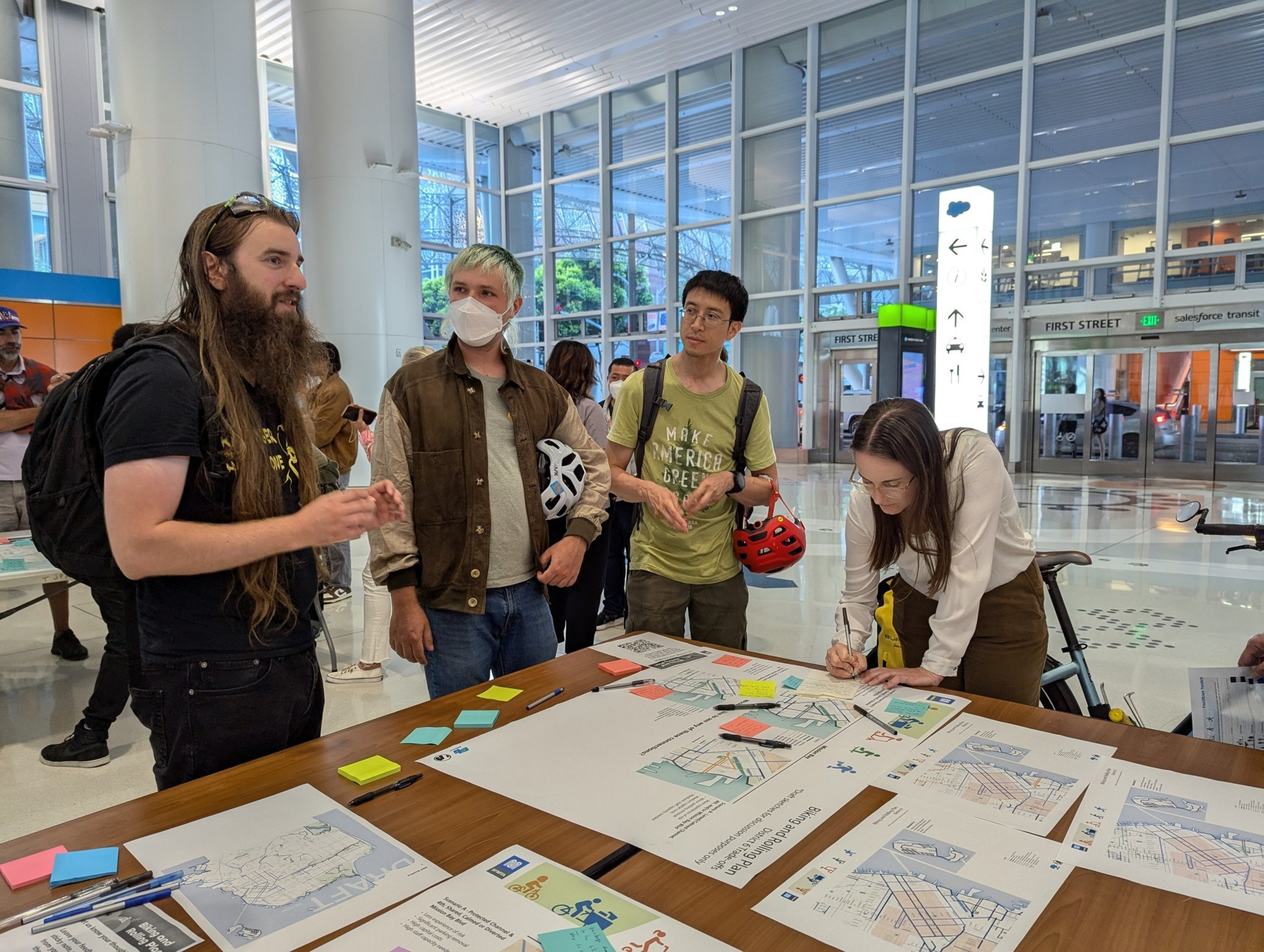

The SFMTA did, however, have scenario maps that were up-to-date enough to print out and tape to columns in the Salesforce Transit Center during the latest open house on Wednesday. So readers will have to do their best to puzzle out the potential changes to their neighborhoods based on cellphone photos of maps.

Just how cartographers intended.

Never enough voices

The Biking and Rolling Plan is an ambitious project aimed at setting San Francisco’s priorities for the coming 15 years for building infrastructure for cyclists, scooter riders and anyone else rolling down the street. San Francisco has built (opens in new tab) more than 50 miles of protected bikeways in the past decade. But there are still significant gaps between many of those bikeways, meaning cyclists often have to traverse unprotected city streets to get where they’re going. The goal of the plan is to eliminate that problem by creating a network of bike infrastructure that runs within a quarter mile of every block in the city.

In the leadup to this summer’s open house tour, the bike and roll team conducted two phases of citywide outreach, hosting no fewer than 90 community events. Despite that, the plan is still in its “very early stages,” and the open houses are not intended to present a finalized plan, but rather to collect more feedback, according to SFMTA spokesperson Michael Roccaforte.

The lengthy outreach progress has frustrated cycling activists.

Transportation activist Stephen Braitsch thinks SFMTA wastes staff time and money on “extraneous” outreach out of fear of public backlash that will come regardless.

“No matter how many times [SFMTA staff] talk to people, people will still complain that they were not heard,” Braitsch said.

And that has indeed proven to be true with the Biking and Rolling Plan. Just the idea of a bike lane running through Chinatown was enough to spur neighborhood activists into pressuring Mayor London Breed to spike it. Breed’s office leaned on SFMTA, leading to the only guarantee to come out of the Biking and Rolling Plan thus far: The city will not build a bike lane in Chinatown.

“We are never going to achieve a citywide interconnected network if we are skipping over one entire neighborhood,” said Claire Amable, director of advocacy at the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, in response to Breed’s Chinatown decision. “It’s incredibly disappointing to see elected officials back down from their own transportation policies and their own Vision Zero goals in this way.”

‘The Valencia fiasco’

There could be another reason the bike plan seems stuck in its larval stage: not wanting to anger potential voters.

“I can’t help but think that there’s a mayoral election in November and that pushing it out past that seems like a really convenient move,” said Bornheimer.

Tom Radulovich, who served on the policy advisory committee for the Biking and Rolling Plan, also speculated that fears of upsetting communities could be making Breed’s administration hesitant to put out more specifics on the plan ahead of the election.

Some of Breed’s opponents have already staked out more car-friendly stances, potentially putting them in a strong position to capitalize on ire generated by bike lane plans. Meanwhile, anger over SFMTA’s Valencia Street bike lane changes has sown distrust in the agency.

“The Valencia fiasco is hanging over this whole effort,” Radulovich said. “The politics are making this conversation harder to have.”

A mayoral spokesperson denied that any delays stemmed from fear of controversy ahead of the election and emphasized that the Biking and Rolling Plan is an important component of Breed’s transportation vision for the city.

Despite the controversy swirling around the plan, there was considerable optimism at the SFMTA open house Wednesday, which presented different visions for how the city may approach its Bike and Rolling Plan. A casual viewer could tell the crowd was pro-biking, judging by the many helmets hanging from backpacks.

Most cyclists threw their support behind Scenario A, adding that they liked the school zone suggestions in Scenario C.

“I’m excited about it,” transportation advocate Trish Gump said of the plan. “This is a way for San Francisco to really transform itself.”

SFMTA Project Manager Christy Osorio, who is leading the Biking and Rolling Plan process, was glad to hear it all.

“I don’t think you can do too much outreach,” Osorio said. “It’s really about transparency.”

Three scenarios

So, what are the scenarios that SFMTA is considering as it develops its Biking and Rolling Plan?

- Scenario A: The city relies heavily on bike lanes that are physically separated from traffic by a barrier, creating the most safety but also coming with a larger price tag and loss of parking spots.

- Scenario B: The city sacrifices fewer parking spots by nixing most of the physical barriers for bike lanes, instead opting for painted bikeways.

- Scenario C: Instead of focusing on bike paths, the city would reshape streets within 1,000 feet of schools to slow drivers down, though exactly what changes that would mean are yet to be determined.