However much the Golden Gate Bridge may be a sublime symbol of San Francisco and a magnificent architectural achievement, it is also a place of death. But a barrier designed to keep people from jumping off the 87-year-old Art Deco span is saving lives only eight months after its completion.

Data indicates that only four people have died by suicide on the Golden Gate Bridge so far in 2024. That is approximately 20 percent of the annual average for this date, according to bridge authorities.

Since the bridge opened to traffic in 1937, close to 1,800 people have ended their lives by jumping into the chilly currents 200 feet below the road deck. In 2013, the most recent peak, an astounding 46 individuals took their own lives (opens in new tab). Over the past five years, the average has been in the low 20s, or almost one every other week.

In response to this persistent trend, anti-suicide advocates led by survivors’ groups (opens in new tab) proposed two “nets” along both sides of the bridge, as much to catch anyone who leaped off the parapet as to prevent them from trying. Opponents pushed back vigorously, citing both the threat to the bridge’s aesthetics and the belief that anyone determined to take their own life will find another way to do so.

Ultimately, the advocates won.

Beginning in 2018, the bridge district invested $224 million to install (opens in new tab) deterrents under both railings along the bridge’s full 1.7-mile length. The project took more than five years, but the infrastructure was fully in place (opens in new tab) by the beginning of this year.

Eight months after their completion, data indicates that the deterrents are functioning as intended. “In a typical year before the net,” Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District spokesperson Paolo Cosulich-Schwartz said, “there would have been 15 to 20 suicides at this point.”

This year’s figure, of course, is four lives too many. But it represents progress, nonetheless. In fact, there was a three-month period this year when, for the first time in almost nine decades, there were no suicides at the Golden Gate Bridge.

Caught in the net

The suicide deterrents, which are not readily visible to pedestrians or cyclists crossing the bridge, much less to drivers, are not what most people think of when they envision a net. Certainly, they are not the springy mesh used to protect high-wire aerialists.

Rather, they’re marine-grade stainless-steel wire rope, akin to a horizontal fence four millimeters thick, positioned 20 feet below the roadbed and extending 20 feet out. Anyone who jumps into this net is likely to be injured.

“It ain’t a pretty fall,” said a bridge maintenance worker who declined to give his name because he was not authorized to speak with the media. He couldn’t remember the last time he witnessed an intervention, when authorities successfully persuade people at imminent risk of suicide to reconsider.

That’s because the secondary purpose of the nets isn’t to catch jumpers, but to prevent them from jumping in the first place. In that area, too, they are working as planned.

“In a typical year before the net, our staff would successfully intervene with between 150 to 200 people annually (and through July, we would expect to have performed between 90 to 120 successful interventions),” Cosulich-Schwartz said by email. “Through July 2024, there have been 66 successful interventions.”

Kevin Hines is one of only a few dozen people who are known to have jumped off the bridge and survived (opens in new tab), having made the attempt on his own life in 2000.

Since that moment of despair 23 years ago, he has worked with the Bridge Rail Foundation, which his father founded, to raise awareness about suicide prevention. He notes that “reducing access to lethal means” is the best way to stop someone in time. The popular belief that people will just find another means is untrue.

More importantly, he added, suicidal ideation is not the same as an urge for self-harm — in fact, they’re almost opposites. “People don’t want to get hurt. They want to die,” Hines said. “They’re trying to take the lethal emotional pain out of their life by disappearing forever.”

In other words, most people don’t first jump into the net before making a second jump into the water below — because the fear of experiencing pain is sufficient to hold them back.

Moreover, the same construction that makes the suicide deterrents painful to land on also makes them difficult for the untrained eye to discern, answering the criticism that they might mar the icon’s charm.

Giovanni Borges, an attorney from Miami who was visiting San Francisco for the first time, said he wouldn’t have known the nets were there if a reporter hadn’t pointed them out.

“I wouldn’t have noticed, and I’ve been sitting here for two hours looking at the bridge,” he said. “I think if you have even a chance of saving one person’s life, it’s worth it.”

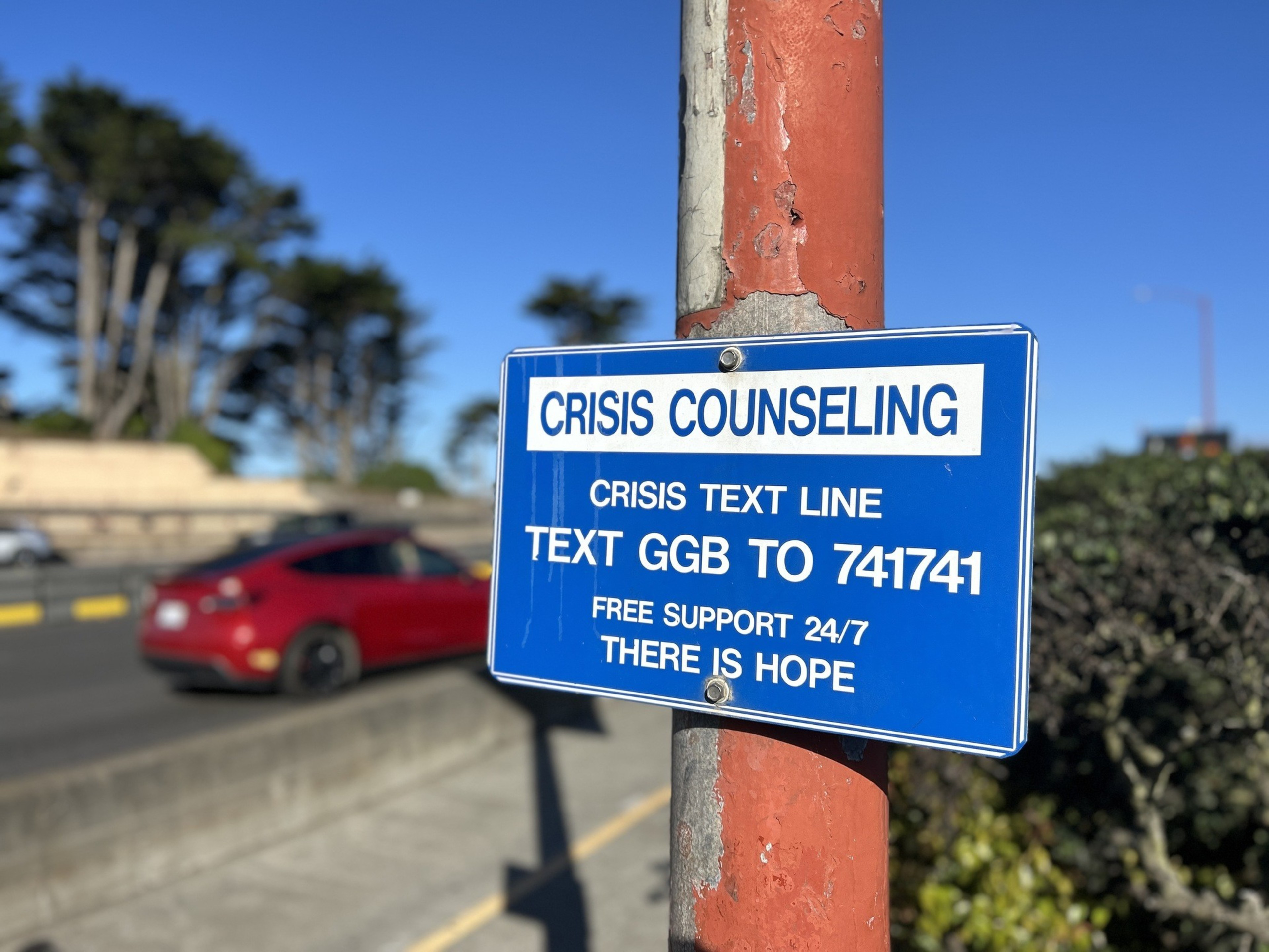

If you or someone you know may be struggling with suicidal thoughts, you can call or text “988” any time, day or night, to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or chat online (opens in new tab).