This is The Looker, a column about design and style from San Francisco Standard editor-at-large Erin Feher.

Anand Sheth’s three-bedroom Victorian flat, nestled on a leafy street between Noe Valley and the Mission, isn’t just the architect’s dream home. It’s a microcosm of his philosophy about cities. Although the building was constructed in 1895, its occupants have shifted so dramatically, and so numerously, that it can’t be said to be the same place it once was.

“Cities are just a bunch of people who choose to be together,” says Sheth (opens in new tab), who designed San Francisco-defining locations for Sightglass Coffee, Tartine Manufactory, Popi’s Oysterette, and Hi Felicia. “We define it and make it real.”

The Victorian, graced with a quartet of turned entry columns and faceted dentils, was originally a spacious single-family home that was subdivided into three units in the 1950s. When Sheth moved into the top-floor flat in 2011, he shared it with four roommates, and every room except those containing a stove or a toilet was occupied by a bed. The home’s only identifiable style at the time was classic Craigslist roommate maximalism.

Today, Sheth is the sole tenant, having outlasted all his roommates and annexed the place for himself. Each room is painted a different color, with the most dramatic spaces featuring an eye-catching multitude of perfectly matched hues. There’s custom lighting and furniture, and walls hung with pieces from up-and-coming international artists. Sheth’s architecture and design office occupies one of the former bedrooms. There’s another spare for guests, or just for reading, doing yoga, or smoking a joint with friends after dinner.

When Sheth moved in, there were peeling pergo tiles on the floor, and the walls exhibited decades’ worth of poorly executed paint jobs. Back then, Sheth was a scrappy student at California College of the Arts and an intern at Boor Bridges Architecture; he now wishes he could say he saw the building’s potential. But, he recalls, he was mostly just grateful for an affordable room in a fun neighborhood.

Over the next few years, 13 roommates, not counting the rotating cast of romantic partners who accompanied them, would cycle through the space. Sheth stayed put but shuffled around the house. His first bedroom was where his office is now; like a design-minded Goldilocks, he tried every single one, even dragging his bed up the steep step ladder to the charming but uninsulated attic.

He and various roommates chipped away at repairs and upgrades over time, tiling the bathroom, replacing the floors, and swapping out rickety lighting fixtures and wonky doors, all with the support — both moral and financial — of their landlord.

“My landlord’s really in touch. He’s actually one of the few good ones,” says Sheth. “He used to rent the attic room in the 1970s. Then, when his landlord was looking to sell, he ended up buying it.”

Sheth’s stars aligned similarly. Just as he was becoming more established in his career and could afford some extra space, a roommate would move out. He stopped looking for replacements, and eventually, it was just him and a live-in girlfriend. When that relationship ended, he had the entire 1,800-square-foot flat all to himself.

“I stuck around through lots of change, lots of people, lots of relationships, and 13 years later, it’s me, my office, and my dog. That’s the dream. I got my castle on the hill.”

Up there with the weirdos

Being able to spread out inside his own little slice of San Francisco is especially sweet for Sheth. His parents emigrated from India and settled in Los Angeles, but his father had spent time as a young man exploring San Francisco and fell hard for it. Sheth’s photo albums are rich with photos of him as a child, posing with his family with live crabs at Fisherman’s Wharf, standing windblown on the Golden Gate Bridge, and smiling in the backseat after a trip down Lombard Street.

“My dad’s a very romantic guy — my whole childhood he would talk to me about the cable cars and the hills and the fog and all these things he really appreciated about San Francisco,” recalls Sheth. “And if we ever had a three-day weekend, we would just drive up here.”

When it came time to go to college, the city was an obvious choice. “I thought, ‘It seems like there’s a bunch of weirdos up there, and I don’t fit in here [in L.A.]. So let’s see what comes out of this,’” he says.

What came out of it was an intensive yet expansive architecture education, deep and long-lasting friendships with fellow artists and designers, and a decade-long career at one of the city’s most celebrated firms, Boor Bridges Architecture.

“I started as an intern in college and was the design director 10 years later,” says Sheth, who was cruising toward career altitude when the world as we knew it was knocked from its axis in 2020. But just as the pandemic annihilated any semblance of predictability, Sheth decided to take a few risks of his own.

“I thought, what better time than now? It’s already scary; I might as well do the scariest thing I’ve ever done.” He left Boor Bridges and launched his eponymous firm in 2021. “I figured if I was going to spend a lot of time trying to float a ship, I would rather just do it for myself.”

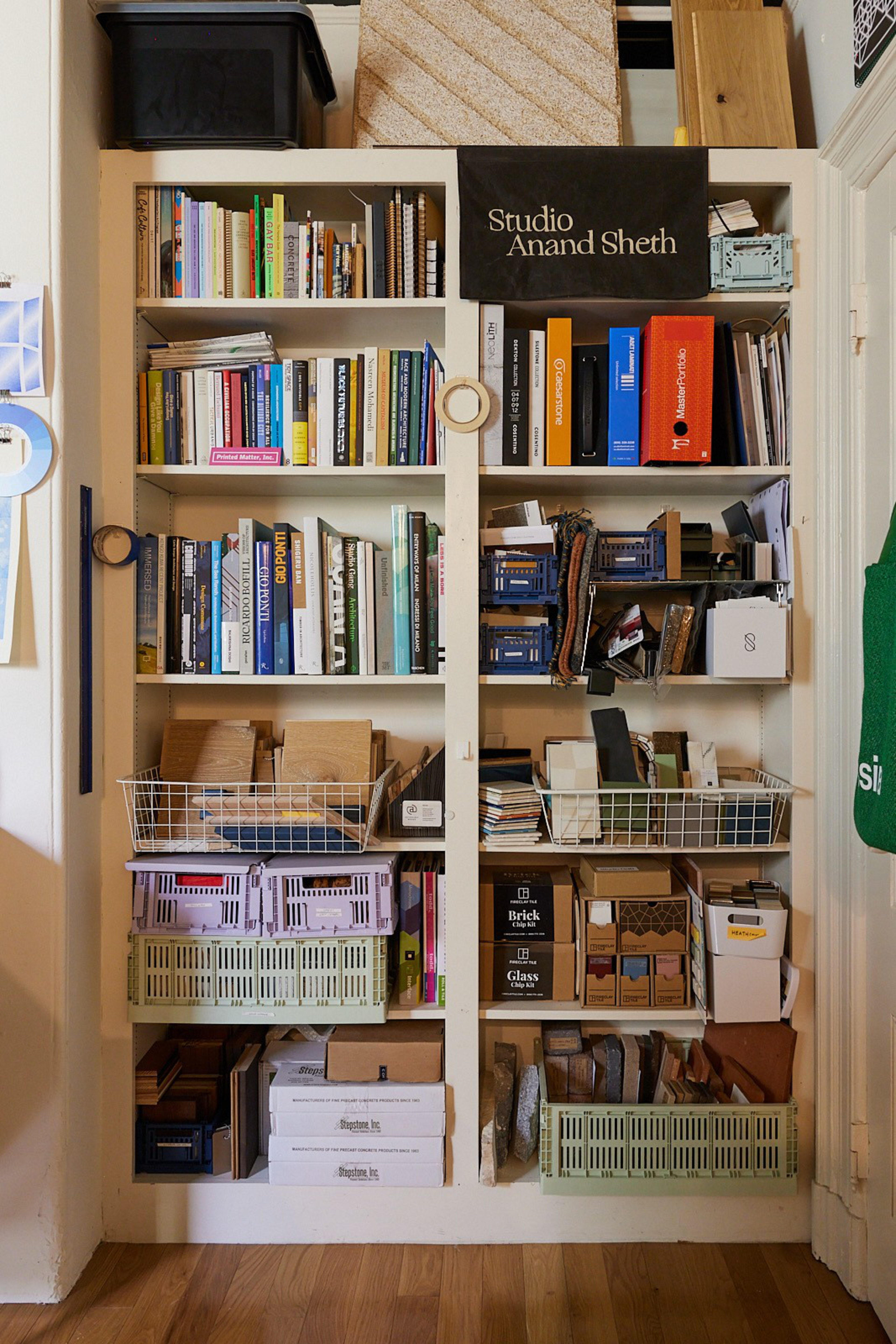

Setting up his office in his former bedroom felt like a full-circle moment. He brought in his library of architecture tomes, material samples for his inaugural projects, and at least a dozen beloved artworks to hang behind his desk.

He sleeps in a space that worked as a bedroom only after the house was out of its roommate era. The room opens via double glass sliders to a spacious back patio that wraps around to the kitchen. Generous and ever-changing sunlight tints the walls — painted a shade of beachy coral — into various moods of peach and pink, depending on the angle and time of day. A riot of greenhouse plants nearly cover one wall, while the others display small paintings, photographic prints, and mounted sculpture, almost always in pairs by the same artist.

The attic comes in a close second for the coziest place to crash. The climb is a bit treacherous, but the exposed redwood rafters strung with fairy lights make it worth it. The deep eaves lend the space a secret-hideout feel, and the collection of layered rugs — all castoffs from other rooms or projects — make the space ideal for lounging. Sheth says it gets the most use as his yoga studio or an afterparty spot following dinners with friends.

The home’s showstopper is the street-facing double parlor that holds the living and dining rooms. A deep, molten red covers the walls just past halfway. A second hue takes your eyes up to the 11-foot ceilings. In the dining room, it’s a smoky navy, while the sitting room gets a brighter off-white. A custom daybed in the deep bay window is where you’re most likely to find Sheth, cuddled with his dog, Gilligan, a custom ashtray-cum-cupholder perched alongside.

Taking pride of place on a coffee table is a striking and slightly sinister-looking vase filled with serpentine lotus pods, articulated carved-wood snakes forming the vessel’s ribs. Sheth’s art collection isn’t of the sort that fades into the background or complements the rug.

Tracing back to his days at CCA, he is part of an ever-expanding hive of local artists, and in addition to collecting for himself and clients, he recently started curating buzzy, nontraditional art shows in San Francisco and L.A. The snake vase, “Heads and Tails” by Caleb Ferris (opens in new tab), was part of Sheth’s latest group show, “Vessel.” (opens in new tab) It featured 27 artists with Bay Area roots and will be revived through September, when a selection of the pieces are exhibited in small businesses and galleries around the Bay, including The Sidewalk Flowers (opens in new tab) in Cole Valley, the concept shop Strip Mall (opens in new tab) in Lower Nob Hill, LNB Atelier (opens in new tab) in China Basin, and Sawmill Studio (opens in new tab), a loft studio in Oakland’s Sawmill Building.

For the show, all the artists were asked to explore the idea of a vessel. “For many of the artists, the vessel represented a body on Earth or body in a city and/or a body in their culture,” Sheth says.

It’s yet another meditation on the themes that have been tugging at him recently, especially as he watches the constant evolution of a city that has been part of his identity for generations, and one that he plans to call home for a long time.

“It’s the contents that actually give us something to respond to and talk about,” he says. “It’s the lives inside that make it real.”