Want the latest Bay Area sports news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here to receive regular email newsletters, including “The Dime.”

LAS VEGAS — Not long ago, Lainn Wilson was driving the team van through the snowy midwest and running gear through laundry machines after games. He was the video intern for the Grand Rapids Drive, the Pistons’ D League affiliate — “lowest of the lows,” he said.

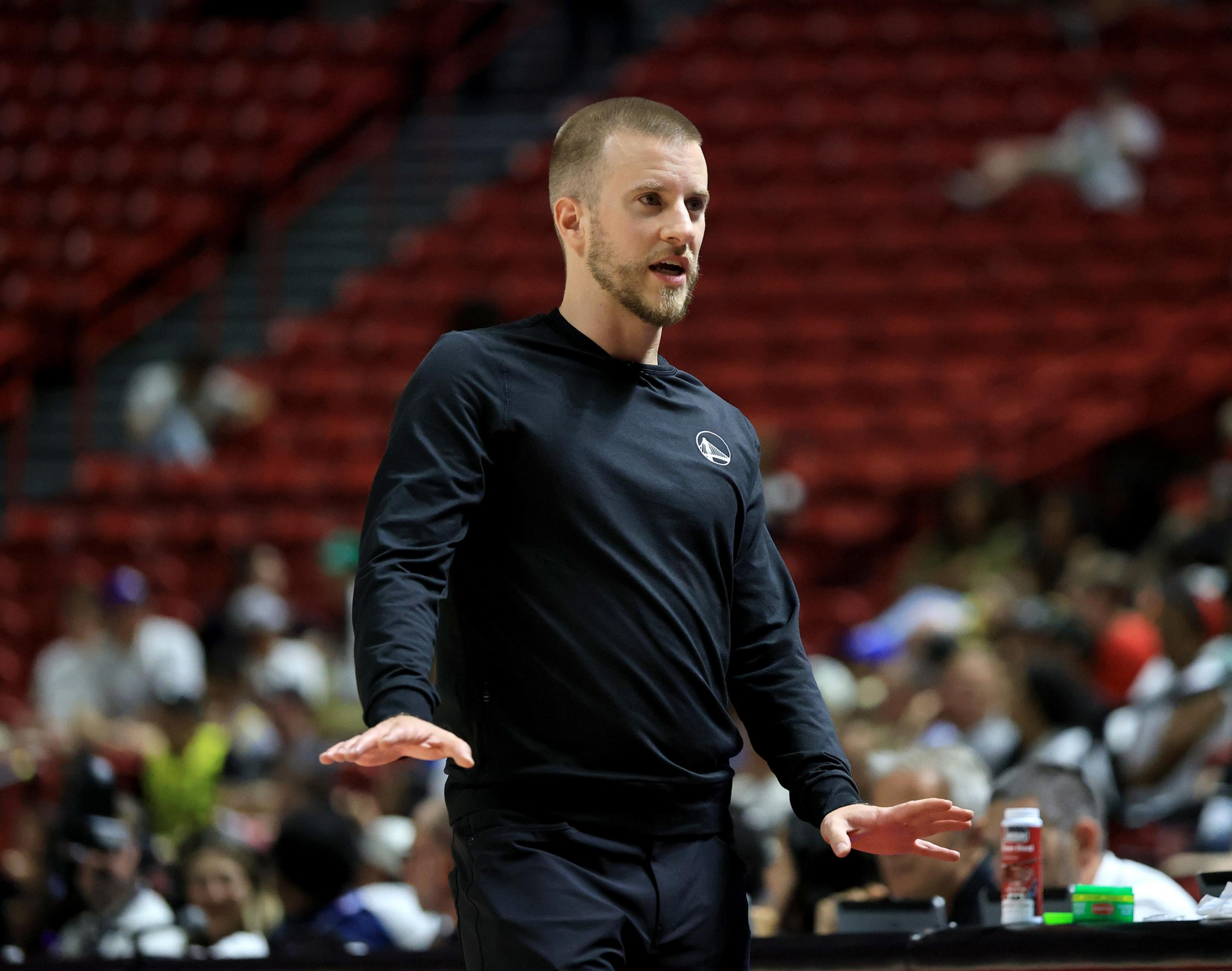

Wilson has climbed up the basketball ladder one rung at a time. From student manager to graduate assistant, to video intern and laundromat coordinator, to D League assistant coach. Now he’s going from head video coordinator with Golden State to Summer League head coach, which will parlay into the same role for the Santa Cruz Warriors when the season arrives.

Wilson, 33, didn’t play basketball beyond high school. He wasn’t born into an NBA family. He had to make his own connections, carve out his own niches, forge his own reputation.

“Everyone’s journey is different, so I respect everyone’s journey, but his journey is just, like, the hardest way to make it,” Warriors player development coach Noel Hightower told The Standard.

Section 415: How Natalie Nakase turned the Valkyries into an immediate force

Section 415: Tim Kawakami analyzes the 49ers, Giants, and Warriors

Section 415: Min Woo Lee, Steph Curry, and the story of The Bay Golf Club

“You miss birthdays, holidays, you miss Christmases — we play on Christmas. You miss Thanksgiving, you miss funerals, you miss weddings, you miss graduations. You sacrifice all those things. It’s one thing to sacrifice all those things and make millions of dollars, but Lainn has sacrificed all those things throughout his career and made pennies on the dollar.”

A path less traveled doesn’t mean the terrain is impossible. Two of the NBA’s finest coaches, Erik Spoelstra and Mark Daigneault, followed similar tracks.

Wilson never considered quitting. Not even those nights when he was starving after finishing up that last load of laundry, and the only option in the middle of nowhere was Applebee’s, again. The energy of competing, of helping a team of people pull together in the same direction, has always been too intoxicating for Wilson.

“I think everybody experiences a couple moments where, you know, you’re driving the van, it’s snowing outside, you’re by yourself, and you’re wondering, ‘How did I end up here?’ or ‘Where am I?'” he said. “But I think those moments are totally normal, and they come and go. There’s always those. The next day rolls around, and you’re kind of ready to go again.”

Those moments have brought Wilson here, to Las Vegas and, soon, to Santa Cruz, as the leader of a program.

Stepping into the spotlight

Wilson kept his team in the locker room at halftime for a touch too long in Golden State’s California Classic finale. When players returned to the court, the officials tagged the Warriors with a delay-of-game violation.

“F— that.” Wilson muttered under his breath along the sidelines.

One game later, his third ever as a head coach, Wilson profusely signaled for a review on an off-ball foul called on Jaden Shackelford. There was 5:23 left in the Warriors’ Las Vegas Summer League opener, and Shackelford had gotten tangled up with Yang Hansen in transition. The coach was pissed — so pissed he picked up his first career technical foul three minutes later.

“There were frustrations in the last game that I kind of let dictate how I acted,” Wilson told The Standard.

“I pretty much crossed the line in both those instances. I’m a work in progress, still figuring it out. I want to project to our guys to be composed and still have an edge to them. I’m still figuring out what that is for myself, because I don’t want to teeter over that line.

“I do think that when you’re in that leadership role, it can affect everything from the top down. Your players can sense that you’re on edge, you’re not really in control of your emotions, then that can trickle down to them, and that doesn’t do anyone any good.”

In the film room, you don’t have to worry about technical fouls, about how your demeanor can bleed onto the court. Going from head video coordinator to head coach is a big leap.

Especially in Summer League.

The summer format brings random players together at a moment’s notice, with hardly any practice time for them to coalesce. Because players try to use the showcase to earn contracts with teams, there are competing agendas. Everyone’s anxious to make the most of their chance. The games are physical, with a 10-foul limit instead of the typical six per player.

“I think the Summer League is a great buffer for going into the season,” said Everett Dayton, a Warriors player development coach and summer assistant. “It’s super tough, because you’re getting a bunch of people who have never played together before. It’s a pretty big moment for them. I think there’s a lot of nerves involved.”

Summer League wing Blake Hinson averaged 20 points per game for Santa Cruz last year, so he’s likely in line to get a lot of time with Wilson this year. At the start of Summer League, Hinson asked Wilson to be an “a-hole” to him about his defense.

That’s not exactly Wilson’s style.

“He hasn’t really answered the bell on it,” Hinson said. “He’s been on me about it, but he’s not been enough of an a-hole as I’d like him to be. He’s trying to be nice about it.”

Not every player will be as direct with Wilson as Hinson was. The first-time head coach must figure out what makes each of his players tick and how to motivate them. He’ll have to find the balance between holding players accountable for their mistakes and building up their confidence.

“I’m still trying to find that mix for different players,” Wilson said.

Hightower said a head coach needs to have “one thing you’re really special at,” and Wilson has two: video and X’s and O’s. That’s the foundation. All the intangibles in between will have to come, and the only way to develop those is by doing.

Golden State destroyed Utah in its second game in Las Vegas, overcoming the Jazz’s physicality so much so that their frustrations boiled over. Utah forward Kyle Filipowski picked up seven personal fouls and a technical — one of three in the fourth quarter alone.

Unlike in the Warriors’ first Vegas game, Wilson struck a stoic tone on the sideline. His team’s composure reflected that.

“I think better than the last game,” Wilson said when asked about his team’s poise. “Probably last game was a little bit more of my fault; I think I was a little bit on edge with the first game in Vegas and wasn’t composed myself. I think the guys ended up feeding off that.”

After years of teaching in the video room, Wilson is already proving to be a quick study.

Wilson’s foundation

Wilson grew up in Augusta, Georgia, where his dad would take him to gyms and coach him in recreation leagues. He fell in love with the game watching college basketball and, upon stepping onto campus at the University of Georgia, applied to join the men’s team as a student manager.

“He was young, eager, hardworking,” said Mark Fox, then the head coach at Georgia who hired Wilson. “Lainn was really smart. And he got everything done. You give young guys a task, and the ones that survive are the ones that get things done.”

Wilson’s tasks involved managing equipment and rebounding for players. He added film breakdowns, video projects, and sending recruiting mailers. He lived in the office, from sunup to sundown every day, Fox said. His schedule was loaded, yet he graduated with a finance degree.

When Wilson earned a promotion from video coordinator to assistant coach with Grand Rapids, the team had a four-person coaching staff (head coach, two assistants, and a video coordinator). Resources were tight, but that just meant Wilson could shoulder more of the load, including scouting.

“I’ll never forget the way he was able to add more to his plate and do it at a very high level,” said Ryan Krueger, Wilson’s head coach with the Drive.

Those who have worked with Wilson aren’t surprised he earned the opportunity to coach Santa Cruz. They’ve seen his work ethic, attention to detail, and ball knowledge up close. They’ve seen him instantly pull up videoclips from years ago at a coach’s request, seen him explain how to install offensive concepts in chunks, seen him come into every meeting prepared.

Wilson views the game with a progressive eye. Already with the summer team, he has drawn up out-of-bounds plays in the mold of football wide receiver routes — a trend that’s growing at the NBA level.

“He’s probably one of my favorite people to talk hoops with around the organization,” said Dayton, the Warriors’ player development coach.

Wilson received the nod this summer after Nicholas Kerr was elevated from Santa Cruz to the Warriors’ bench. The past five Santa Cruz head coaches are now on NBA staffs. Pros Quinten Post, Pat Spencer, Gui Santos, and Jackson Rowe have spent time with the team as it has become a reliable feeder program for the Warriors.

Wilson has more responsibilities now than ever, though he doesn’t have to do the laundry anymore. For years, he has told friends about his desire to coach one day — “That’s why I’m here in the first place,” Dayton recalled Wilson saying.

His chance to realize that dream, at long last, is here.

“Really whenever you get on the floor with your guys and your team and your staff, regardless of the circumstances going on, I think it’s just a hard feeling to beat,” Wilson said.