Want the latest Bay Area sports news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here to receive regular email newsletters, including “The Dime.”

There’s a mess in Palo Alto, and John Donahoe is stepping right into it.

Donahoe, Stanford’s new athletic director and former Nike CEO, is inheriting the most successful sports department in the NCAA, but also one that has hit rock bottom in the programs that generate the most revenue and attention. The football team — now led by general manager Andrew Luck — is coming off four consecutive 3-9 seasons, the men’s basketball team hasn’t made the NCAA Tournament since 2014, and the women’s basketball program had its streak of 36 consecutive March Madness appearances snapped in March.

The reasons for this precipitous fall are well understood: Under prior leadership, Stanford failed to embrace name, image, and likeness opportunities that allowed universities to funnel big money to elite recruits and high-profile transfers. In the summer of 2022, the Pac-12 dissolved and a coveted Big Ten invitation never materialized. Stanford landed in the ACC, setting up more arduous cross-country travel with a less lucrative media rights deal.

The school still has an appetite to compete at the highest level — and proof of concept in the not so distant past to show it’s possible — but a daunting path remains ahead. Stanford has a massive athletics endowment and wealthy donors, but its 36 varsity sports run a budget deficit (opens in new tab)overall.

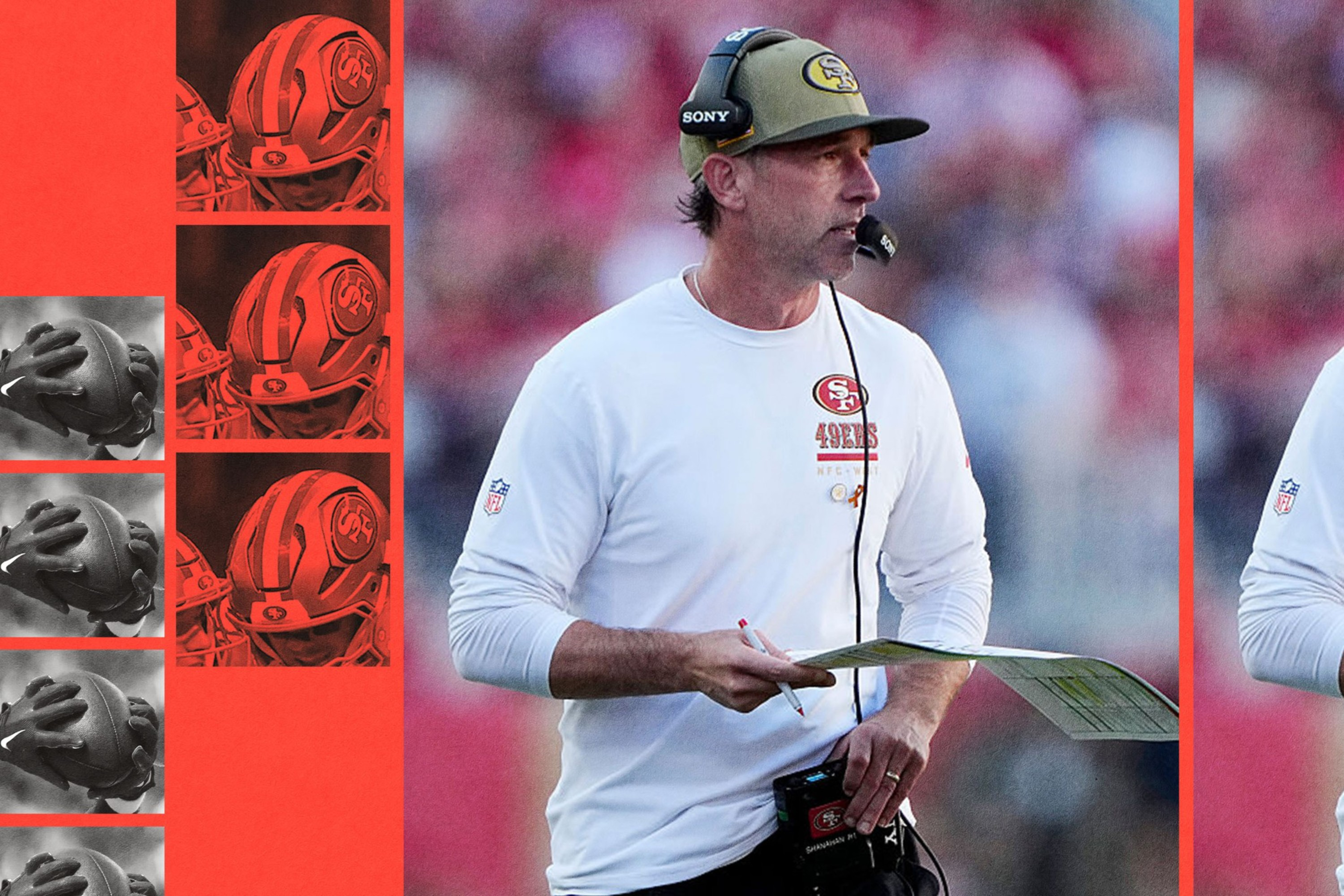

Section 415: Brock Purdy, Mac Jones, and the 49ers’ path to the playoffs

Section 415: Making sense of the Warriors’ uneven start

Section 415: How Natalie Nakase turned the Valkyries into an immediate force

Sign on the dotted line, John.

“That, to me, is what that hiring says — that we want to get on our front foot,” Stanford’s legendary women’s basketball coach Tara VanDerveer told The Standard. “That we want to be a leader in college athletics. Right now it’s a challenge because so much is happening so quickly, that we need someone who has great leadership ability and skills and is a great strategist but also a visionary to see what’s coming around the corner and prepare us for what’s coming in college athletics.”

How Stanford fell behind

When Stanford opens its football season on Saturday against Hawaii, it will begin a quest to snap the longest bowl drought of any power conference team.

Since David Shaw led the Cardinal to its 10th consecutive bowl in 2018, the program has lost more than just games. Some of Stanford’s best players – including 2024 sack leader David Bailey and touted true freshman quarterback Bear Bachmeier – continue to ditch the program, seeking more lucrative opportunities at universities with less academic prestige.

How did Stanford, an institution in the heart of Silicon Valley, with some of the wealthiest donors in the nation, get left behind amid all the change?

“It’s like anything else in college sports: It gets back to leadership,” said college sports journalist Jon Wilner. “Stanford had bad leadership from its president, its provost, and its athletic director for a long time. That led to all these negative downstream developments that have got them in this terrible situation. It’s going to be hard to get out of.”

Under its former president, provost, and athletic director, the university’s embracing of NIL collectives and NIL rules in general was passive if not begrudging.

Women’s basketball star Haley Jones landed a Nike endorsement, but the school didn’t allow her to use the Cardinal logo in ads and made her photoshop the word “Stanford” out of her jersey even as her counterparts faced no such restrictions, according to The Athletic. (opens in new tab) Athletes haven’t been allowed to use campus facilities for NIL activities, and coaches were prohibited from discussing NIL for the first three years of the rules.

“Stanford was super hesitant,” said a source inside the Lifetime Cardinal collective, which helps coordinate NIL partnerships for Stanford athletes. “The previous president, provost, and athletic director were all frozen.”

Unwilling to embrace NIL, the Cardinal got crushed by competitors.

Softball superstar NiJaree Canady left for a $1 million NIL deal at Texas Tech; Lifetime Cardinal reportedly came up well short, at a $350,000 offer. Kiki Iriafen, who went fourth overall in the WNBA Draft, transferred to USC, and her teammate Lauren Betts, a potential No. 1 WNBA draft pick next spring, left for UCLA. The football team lost dozens of players to the portal, either back-filling them with Ivy League-type transfers or not at all.

The confluence of events — some outside Stanford’s control, but many self-imposed — led to the university joining the ACC at a steep discount.

Left in the wreckage was an athletic department desperately in need of a new identity — and new leadership.

Can the new regime awaken a ‘sleeping giant?’

After her illustrious, trailblazing career, VanDerveer retired in 2024 and became a special adviser to the athletic director. She was on the search committee — along with students, alumni, and faculty — that interviewed Donahoe.

Donahoe’s experience in sports and leading large organizations is an asset, VanDerveer said. Aside from serving as CEO of Nike, the businessman and Stanford alumnus worked in the same capacity at eBay and Bain & Company.

“I really think that the hiring of John Donahoe signals, not just to Stanford but to other schools, that Stanford is serious,” VanDerveer said.

There’s optimism within the Stanford athletics community that Donahoe will shepherd in a new era, one that motivates the donor class. And the fastest way to activate Stanford alumni with deep pockets is to field a winning football program.

“If you don’t prioritize football, you’re going to fall behind,” Wilner said. “And that affects everything.”

In 2010, Luck and Jim Harbaugh completed the program’s dramatic turnaround, going 12-1 and winning the Orange Bowl just four years removed from an 1-11 season. From 2011 through 2016, under head coach David Shaw, the Cardinal posted a winning percentage of .790.

The Cardinal have a track record of winning national championships in rowing, water polo, sailing, golf, and volleyball. Success in football is different; it breeds a different kind of attention, of legitimacy. Stanford Stadium suddenly becomes a scene, student applications soar, “College GameDay” comes to Palo Alto (and not, crucially, to Berkeley, as it did last year).

“If we could do it then, we can do it again,” VanDerveer said. “We just need to figure out what contributed to that success and position ourselves to do it again.”

Changes in the NCAA require a new playbook. A Stanford degree isn’t the same carrot if it doesn’t include the type of payday a star can attract elsewhere.

Luck, nine months into his job as general manager, brings energy and cache. Some arrows are already pointing up; the Cardinal brought in 18 transfers this offseason compared to four last year.

“Somebody wrote somewhere that Stanford would be the sleeping giant of NIL if Stanford got its act together, and that’s what we’re doing,” a Lifetime Cardinal source said. “There’s no shortage of people who can write huge checks if the administration wants to do it and wants to mobilize that support.”

The path ahead in Palo Alto

Stanford’s share of the ACC’s media rights deal won’t be full until 2036, meaning the Cardinal will operate at a financial disadvantage in its new conference. It’s just one aspect of the new world order Donahoe and Luck will have to navigate.

The House v. NCAA antitrust settlement allows Division I schools to directly compensate athletes by sharing up to roughly $20 million in revenue with them starting this year.

So Stanford, clawing for a rung on the competitive ladder in the revenue sports while fielding 36 varsity teams, must immediately adapt to one the most significant changes in college athletics history.

“There are obviously tremendous donors that just want to see, where is athletics going?” VanDerveer said. “We’re not just going to throw money at players, we want to have a plan. Let’s see what the plan is. And I think that’s becoming more clear, too. Not just for our donors but for the student athletes, too.”

In addition to revenue sharing, which schools — including Stanford — are expected to spend mostly on football, the Cardinal will have to better coordinate with boosters and collectives to attract recruits and transfers.

Luck, the general manager, must pitch recruits on the future of the program, even though it lacks a long-term coach. Luck hired his former Colts head coach, Frank Reich, as a one-year interim head coach for the 2025-26 season after reports surfaced of coach Troy Taylor’s alleged pattern of inappropriate treatment toward female staffers.

“I didn’t anticipate making a coaching change, but such is life,” Luck said in a KNBR interview this week. “You roll with the punches … and look, this is a year about taking steps forward.”

The university may also have to relax some of its unwavering academic requirements.

“You’re not going to win games by taking transfers from the Ivy League,” Wilner said. “If you’re Stanford, you’ve got to be able to take transfers from the other major conferences. And for years, they have not done that.”

But competing at the highest level isn’t impossible. Harbaugh figured it out. So did VanDerveer for almost four decades. Now it’s on Donahoe, who will officially take over as AD on Sept. 8, and Luck, whose team was picked to finish in last-place in a preseason ACC media poll, to forge a new path.

“It’s all still within their control,” Wilner said. “If they want to take a 300-pound defensive tackle from the SEC, they could. It’s up to them. If they wanted to embrace NIL with their alums and their constituents, they could. I think they’re starting to do that, but they didn’t.

“They fell way, way behind. Stanford could dominate if they want. It’s all willpower.”