Skip to main content

Know Your Neighbors

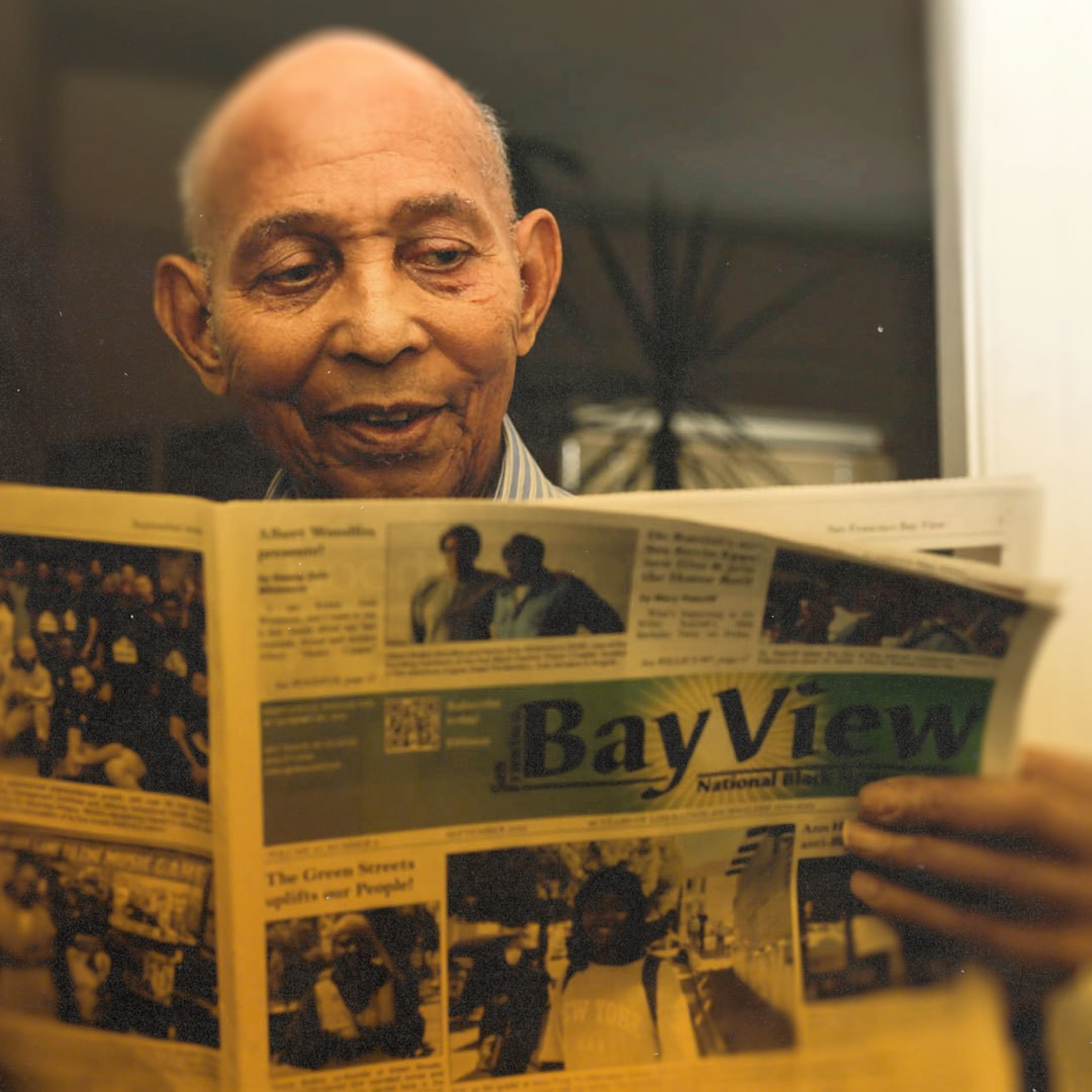

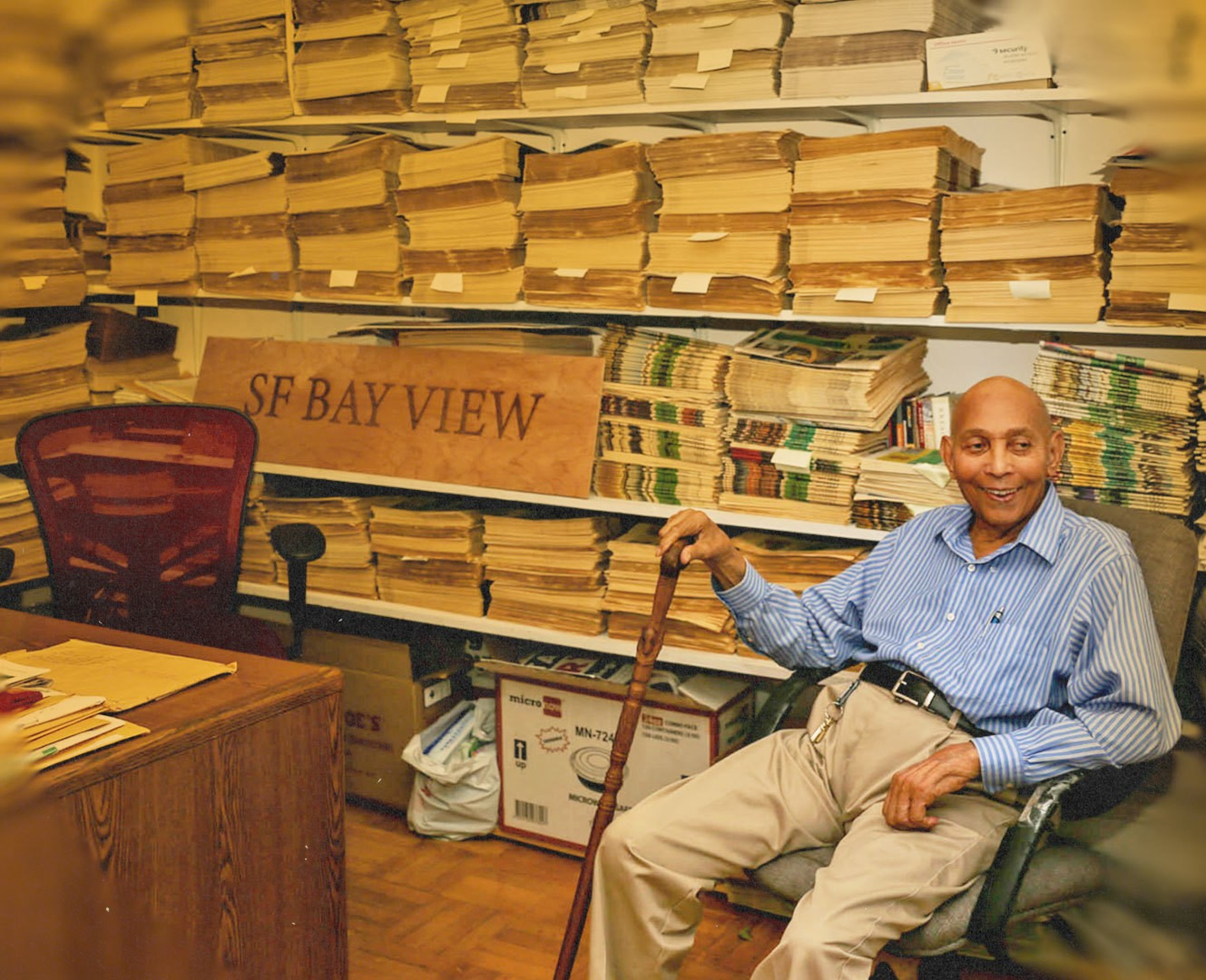

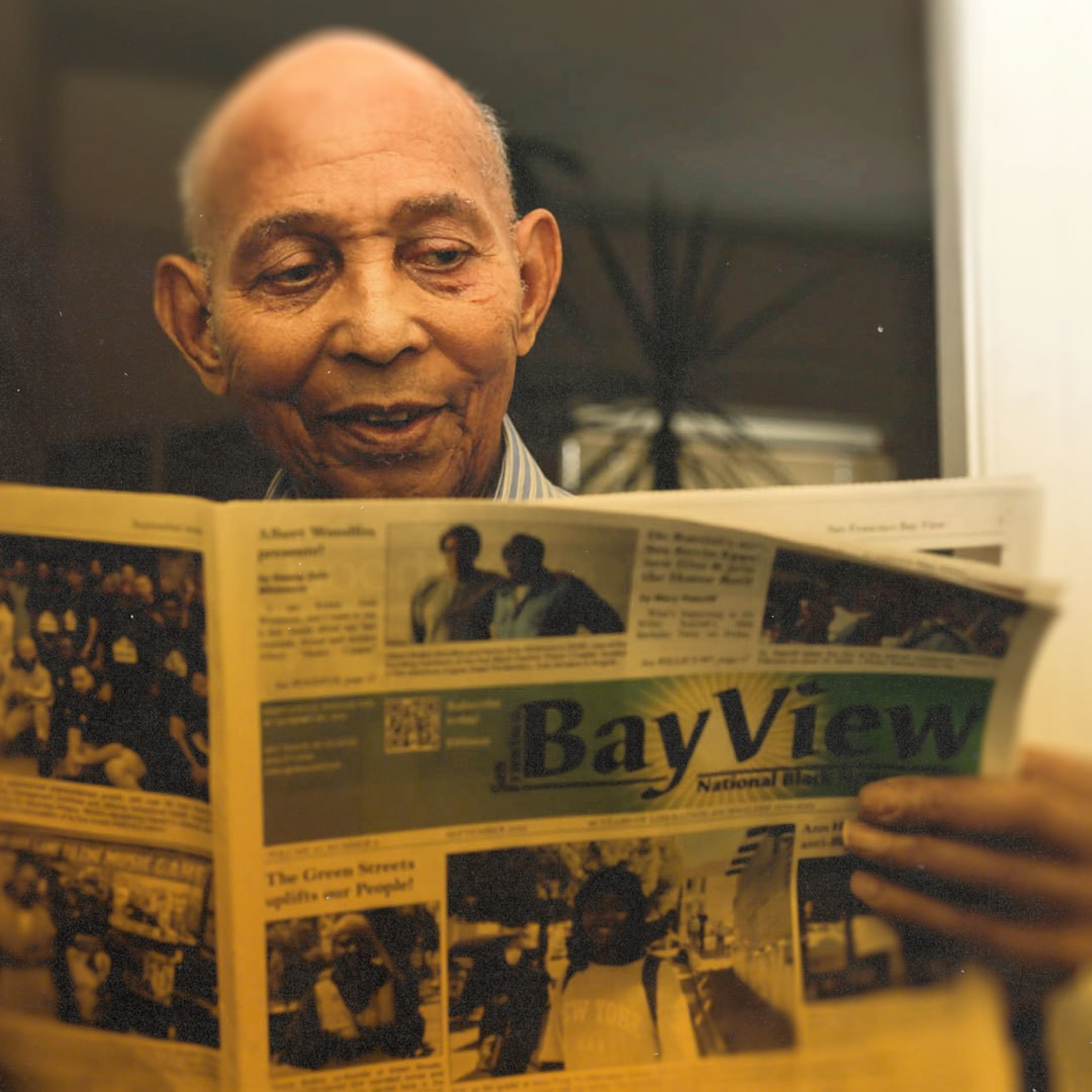

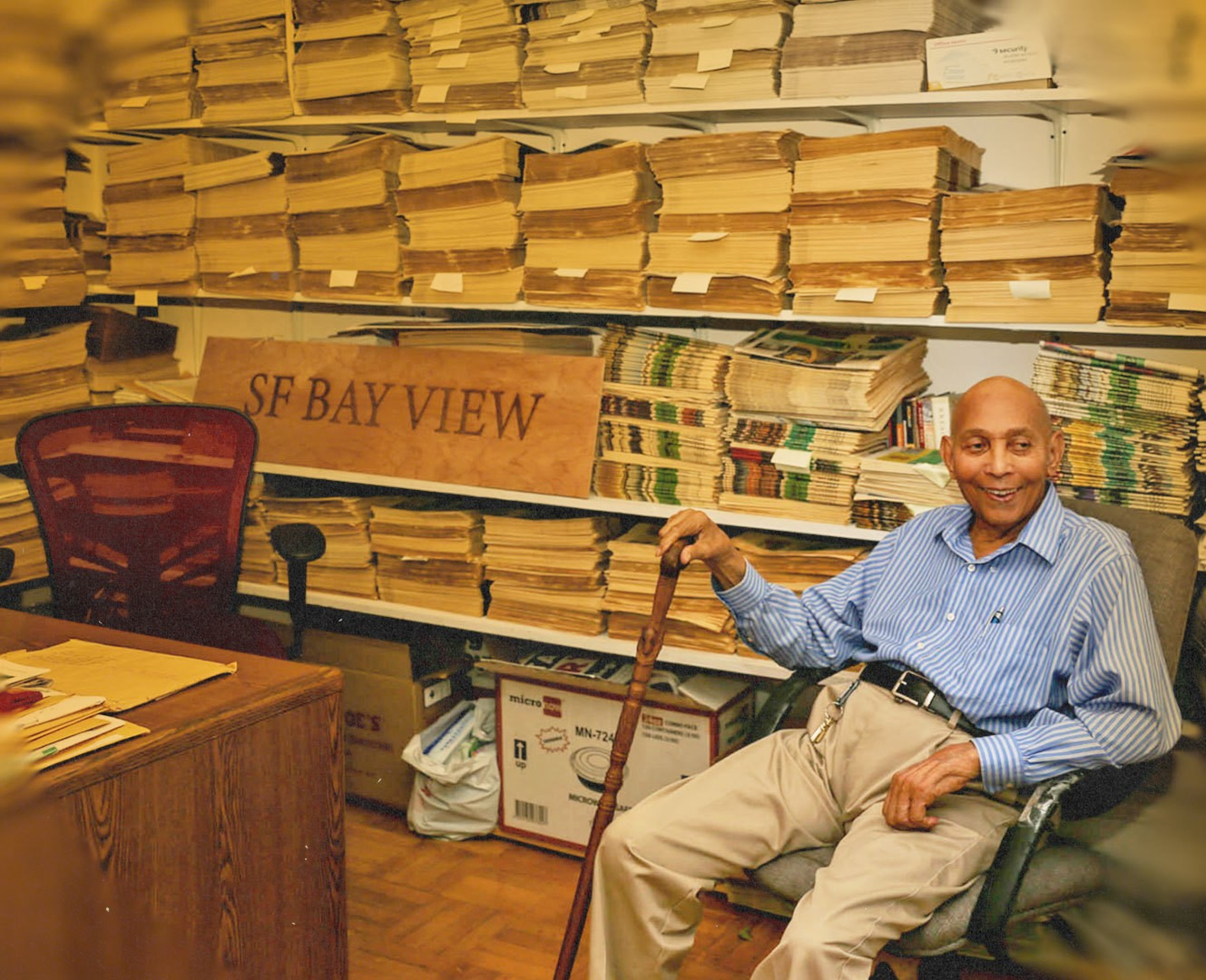

Dr. Willie Ratcliff

Broke Racial Barriers For San Francisco’s Black Workforce and JournalistsWritten by Meaghan Mitchell

Published Sep. 25, 2022 • 10:11am

What prompted Dr. Willie Ratcliff, an owner of a construction firm that had over 500 Black employees at its peak, to pivot away from his business and risk his financial security in order to fight for civil rights in San Francisco? His belief in the power of journalism.

The longtime publisher of the San Francisco Bay View was also driven by his passion for the Black community that once ruled San Francisco’s southeast.

At 19 years old, with one child and another on the way, Ratcliff moved to San Francisco from Texas in 1950. In those days, the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood was a thriving enclave of Black culture. Black-owned businesses filled the commercial districts and homeownership was high—driven in large part by good-paying jobs at the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, where Ratcliff was employed.

“Hunters Point was the happiest hood I’d ever seen,” Ratcliff said.

While working at the shipyard, Ratcliff made $1 an hour—25 cents over minimum wage at the time—but needed more money to support his growing family, so he sought a job in Fairbanks, Alaska, where he could earn $3 an hour on Alaska’s North Slope helping build the Distant Early Warning Line, a system of radar installations designed to detect incoming bombers from the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

However, when he arrived at the Fairbanks office, the dispatcher told him, “No Blacks on the Slope—whites only!” So Ratcliff made a sign, picketed the office, and protested until he got the job.

He lived in Alaska for 36 years and eventually started Liberty Builders, his own construction company. He continued to mobilize around racial justice issues, like fighting for equal voting rights for Black Alaskans and even served as the head of the Alaska State Commission for Human Rights, where he advocated for the LGBTQ+ community and affirmative action in the construction workforce.

When Ratcliff’s wife, Mary, was accepted into law school, the couple returned to San Francisco in 1987. Upon his return, Ratcliff discovered that the city had major development projects in the works, and that there were discussions about giving contractors of color preference in the hiring process. Ratcliff established the African American Contractors of San Francisco to advocate for contracts that were often promised but rarely fulfilled.

“That little group of fewer than a dozen contractors kept at least 600 families in Hunters Point thriving for the majority of the ’90s, until big white contractors perceived Black contractors as a competitive threat,” Ratcliff said.

He continued to work as a political organizer, and in 1990 he learned that the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency—a since-renamed local governmental body with a shameful history of pursuing projects that destroyed Black communities in the name of economic improvement—had its sights set on Bayview-Hunters Point.

“To reduce resistance, City Hall had managed to shut down the neighborhood organizations that used to draw hundreds to monthly meetings,” Ratcliff said, referring to the community groups that enabled the city’s Black neighborhoods to build unified opposition to such projects.

In an effort to prevent his community from being silenced and to keep his neighbors informed, he decided to get into the newspaper business. With no training in journalism, Ratcliff bought the New Bayview for $2,000 from Muhammed al-Kareem, who had founded the newspaper in 1976. He renamed the publication “San Francisco Bay View” and published the first issue on February 3rd, 1992.

At the time, there were two other existing pillars of Bay Area Black journalism—the Sun-Reporter in San Francisco and The Oakland Post—both of which continue to operate as respected newspapers to this day. Ratcliff continued al-Kareem’s mission of advancing racial justice by exposing the controversial issues relating to the lack of economic opportunities within Black neighborhoods. And he invited community activists to use his platform as a soundboard, providing an opportunity for emerging Black journalists to build their audience in the process.

Reflecting on his experiences with racism while living in Alaska, Ratcliff expanded the newspaper’s coverage—looking beyond the neighborhood and elevating stories of systemic racism across the country. “The name ‘New Bayview’ didn’t sound expansive enough, so we came up with San Francisco Bay View (two words), implying a perspective, “a view,” from the Bay,” Ratcliff explained.

With the recently launched SF Bay View Community Journalism Lab, Ratcliff, now 90, is passing the baton and encouraging Black writers and photographers to join his latest project. The newspaper wants to hire “community journalists” to hone their writing and photography skills, report on issues affecting their community, and advance their careers. The fellowship will be led by local journalist and Bayview-Hunters Point native D’Wana Stewart.

Ratcliff is still hopeful about empowering what little of Black San Francisco is left. “I want people to keep pushing, to pool our money together so we can put our people to work, hire each other, and demand reparations and an end to anti-Black racism,” he said. “I want Black people to be welcomed in San Francisco and for the Black population to grow big again.”

Special powers

Guts!

Arch enemies

Racist white people.

Weaknesses

I don’t feel I have one.

Lineage

East Liberty, Texas. It was like Africa. Read the San Francisco Bay View story “Coming home to freedom in East Liberty” to understand.

Current mission

Black power won through block voting, solidarity and having the courage to make demands and make a change.

'I want Black people to be welcomed in San Francisco and for the Black population to grow big again.'