If anyone should be optimistic about the power of artificial intelligence to solve society’s most intractable problems, it’s someone like me.

I was born the only hearing person in a Deaf family. As a kid, I did my best to help bridge communication gaps between my family and the hearing world, where most conversations happen without proper accommodations and Deaf people are forced to rely on lip-reading alone. My family’s struggles inspired me to found Ava (opens in new tab), a communication access platform that captions in real time and identifies speakers, allowing millions of Deaf and hard-of-hearing people to participate naturally in conversations with hearing people.

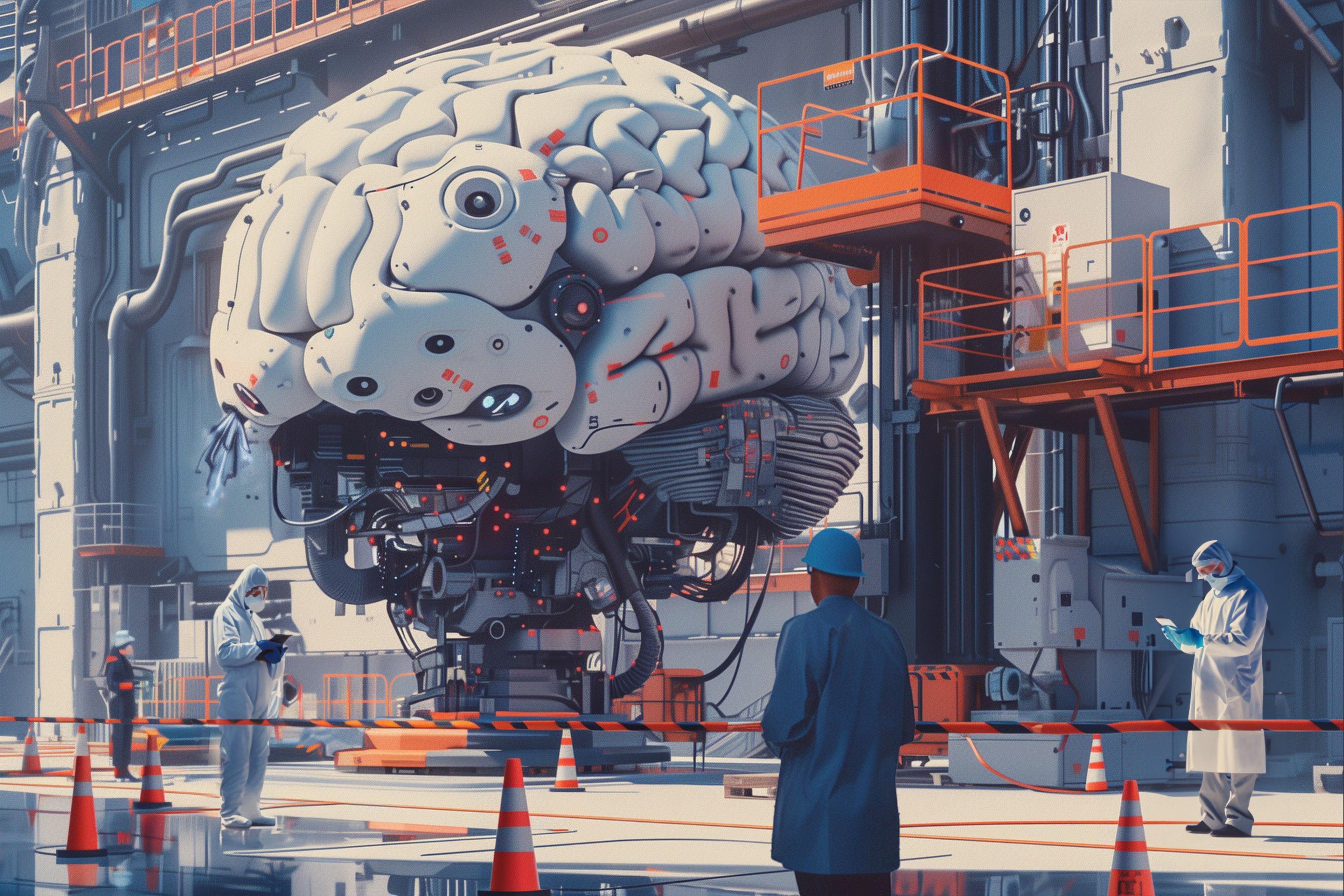

AI powers this technology. But as our society embraces AI and its many potential applications, we must take steps to ensure the most powerful AI systems help humanity instead of harming it. SB1047 (opens in new tab), a bill by Senator Scott Wiener to promote responsible AI innovation, is a crucial first step to help us strike this balance.

On one hand, we want to unleash AI’s power to improve people’s lives. Using Ava’s tools, my sister became the first Deaf trial lawyer in France. AI opened doors that once seemed closed to my family forever.

On the other hand, we need the industry to monitor safety. Ava approaches AI with human oversight for the most important transcriptions. If AI is unpredictable enough to require our communications company to use human intervention, what does that say about powerful new models that can affect critical systems like hospitals or the power grid?

I’m concerned about AI’s ability to cause catastrophic harm to society, creating novel bioweapons or launching cyberattacks on critical infrastructure like the power grid. These threats mostly have not materialized yet, but the National Institute of Standards and Technology (opens in new tab), the Department of Homeland Security (opens in new tab), and Geoffrey Hinton, the godfather of AI (opens in new tab), agree that future models could begin displaying these risks very soon. More than 70% (opens in new tab) of AI researchers express “substantial” concern about potential misuse of the technology.

It’s not just techies who have concerns. Nearly 40% (opens in new tab) of Americans are more concerned than excited about the use of AI in daily life, while just 15% say the reverse. That’s a huge problem. How can AI realize its massive potential to benefit society if we technologists don’t strive to earn the trust of most people?

Many large AI companies have made voluntary commitments to address the risks of AI, and their leaders have publicly proclaimed (opens in new tab) the need to regulate highly powerful AI models. This is commendable. But building real trust in this technology requires our industry to go further. When we see reasonable proposals to do so, such as SB1047, it’s important we put actions behind those words.

A measured approach

Unfortunately, some have already leaped to brand Wiener’s proposal (opens in new tab) as unworkable, anti-progress and anti-innovation.

But SB1047 isn’t some sweeping, recklessly broad overreach. It’s much narrower than the sort of regulatory regime that many AI company leaders have proposed (opens in new tab). If passed by the Legislature and signed into law, SB1047 would not require AI companies to seek regulatory approval before releasing their models. The state could only prevent AI companies from releasing their models if they were deemed an imminent threat to public safety.

SB1047 would simply require developers of the largest and most powerful models to test their ability to enable catastrophic harm. If a developer discovered evidence that their model could be used to create such a catastrophic risk—something significantly beyond what’s possible today with tools like Google—the developer would have to build in guardrails or take other reasonable steps to mitigate the risk before releasing the model.

This is a pro-innovation and pro-startup approach to tackling the difficult problem of making advanced AI as safe as possible. The vast majority of startups, including mine, that are training smaller models would not be affected. The bill’s requirements narrowly target the most powerful models made by a small number of big AI companies with immense resources.

We know that with power comes responsibility. As Ava grows, our models will become more powerful, and we’re looking carefully at the kind of harm this might create. If my company trains a very large model in the future, I would be happy to have SB1047’s requirements help keep us accountable. Safety testing is the least we should be doing for our customers—the cost is minuscule compared to the millions of dollars it takes to train these very large models.

It’s critical that the technology industry engage with policymakers on safety. If we reflexively reject even moderate forms of external governance, we risk spurring regulation that is far more hostile to our industry and much less friendly to innovation.

Thibault Duchemin is the co-founder and CEO of Ava, a live communications platform empowering Deaf and hard-of-hearing people.