Daniel Lurie has promised that accountability will be the watchword of his mayoral administration. Yet, like so many of the promises candidates make — especially first-time politicians making the ultimate grass-is-greener pitch to voters — he hasn’t articulated exactly how he’ll hold himself to account.

For the time being, I’ve worked out a shorthand way of judging whether Lurie is on the right track: If he’s doing things differently than they’ve been done before, that’s a positive sign.

In that regard, his approach to running City Hall is a step in the right direction. As of Tuesday morning, one day before he takes office, the mayor-elect has solidified his team of four policy chiefs who will advise him on a bureaucracy that is more unwieldy than a small city needs it to be.

The last two of these picks fell into place in the last two days, just in time for Wednesday’s inauguration. They are Kunal Modi, a management consultant, whose remit covers departments related to “health, homelessness, and family services,” and Alicia John-Baptiste, CEO of the civic-affairs think tank SPUR and previously a longtime city employee, whose areas are “infrastructure, climate, and mobility.”

Together with economic development and housing chief Ned Segal, an investment banker who became CFO of Twitter, and Paul Yep, a former San Francisco Police Department captain, who’ll oversee public safety, the four promise to be an experiment in soft power in City Hall.

The question: Can an accomplished foursome with varied career experiences but no statutory responsibility over the departments they will attempt to coordinate make a city run more efficiently?

Taking a page from the administration of Michael Bloomberg in New York, the four will sit together in a bullpen office. In theory, they’ll be discussing issues as they arise and will have the opportunity to bring corporate, financial, consulting, government, and public-safety perspectives to bear at every turn. It’s either a recipe for a fresh approach to the city’s problems or a mere rejiggering of who does what.

Modi and Segal bring no government experience to their massive portfolios. That will greatly worry the bureaucrats under their purview, perhaps with good reason. I spoke to both Monday. They share blue-chip professional pedigrees — Modi has been at McKinsey for more than a decade; Segal cut his teeth at Goldman Sachs — and a sense of surprise that they are about to become government employees.

“I had no intention of ever leaving my job,” said Modi, 40. “This was not at all in the cards.” At least his career has been governing-adjacent; he has advised city, state, and national governments and, on a pro-bono basis, nonprofits. He also has volunteered for years in San Francisco for groups like the policy-focused Bay Area Council and Larkin Street Youth Services. His remit will include the Department of Public Health and the third-rail of San Francisco bureaucracy, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing.

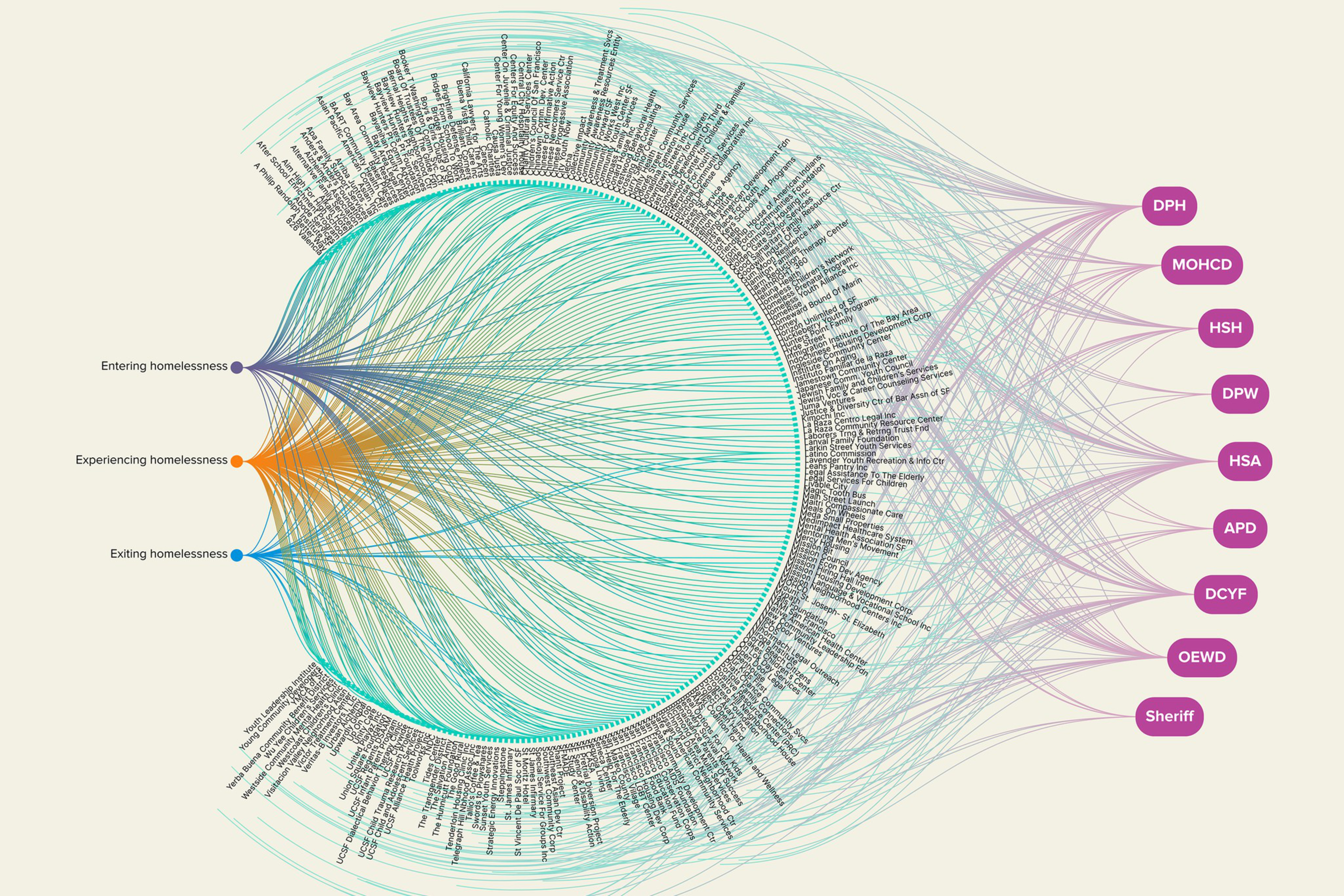

Modi said “better coordination across departments” is the plan of attack. “We have nine different outreach teams, five departments that touch homelessness, and 100-plus contracted homeless providers,” he said. “You can’t manage an approach with that much fragmentation.”

I asked what the right number is, then, and how he plans to achieve it. Modi essentially said he’ll get back to me on that. Fair enough. He hasn’t started work yet.

Segal, 50, was similarly vague on the specifics. He identified his mandate from the mayor-elect, whose campaign he co-chaired and with whom he has been friends for years, as “revitalizing downtown and building more housing.” How exactly the new team will do that will involve “creating process and structure” that’s different from before. “These roles did not exist,” Segal said.

That they exist at all is largely the result of work done by John-Baptiste, 52. Her organization published a report (opens in new tab) this summer that recommended creating “deputy mayor-like roles” that would reduce the mayor’s number of direct reports, a workaround for a voter-approved city law that prohibits the mayor from naming powerful deputies. Before coming to SPUR, John-Baptiste held multiple jobs for the city, including at the Department of Planning and the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. (She’ll oversee the latter, while Segal will oversee the former.)

City Family types are cheering John-Baptiste’s appointment, not only because she is one of their own but also because she is known as an outstanding manager with a deep knowledge of how the city works. “She is analytically sharp and interpersonally astute,” one told me. “She is patient and calm in a way many elected officials and department heads are not.”

Yep, 56, has the narrowest experience of the group. He’s a career cop with a reputation for getting things done, being a law-and-order captain, and having deep ties in the Chinese community. (However, he enters office with a light stain on his record. The Standard revealed Monday that Yep was accused of driving drunk and abusing authority after a traffic incident in 2016. Already, Team Lurie’s image isn’t as squeaky-clean as it would like to project.)

Can a group of middle-aged careerists with no experience working together, under the supervision of a first-time politician, effect the kind of change San Francisco needs? We’re about to find out.