As a severe three-year drought strains water supplies across California, Bay Area water agencies are increasingly looking to the city of San Francisco as a lifeline. Through the Hetch Hetchy dam and a network of aqueducts and reservoirs that brings water from the Sierra Nevada mountains to the coast, the city has plenty of water even now. And it’s fighting hard to protect its position, battling in court against state efforts that could reduce its supplies.

That’s good news for San Francisco residents, who have been asked to make only a token reduction in their water use even amid a drought emergency.

But the small cutback belies bigger trends that make San Francisco’s water resources look a little less bottomless. About two-thirds of the Hetch Hetchy water is sold to wholesale customers, including neighboring cities and counties, and they are being asked to make much bigger cuts in consumption.

This year, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission asked for a voluntary 11% cutback across the system, which meant that some customers were asked to cut usage by as much as 35%. Meanwhile, many neighboring cities have to reduce their collective water use by closer to 16%. City residents, though, only have to trim by 5%—reflecting both the city’s powerful position in the water system and the fact that cool and farm-free San Francisco has the lowest per-capita water usage in the state (opens in new tab).

At the same time, some neighboring urban areas are becoming more dependent on water from San Francisco as they face dwindling supplies from the state water project and other sources. The SFPUC says it can provide—for now.

The city’s obligations to its neighbors were hashed out in a series of lawsuits and negotiations in the 1970s and legislation in the early 2000s, giving the 28 wholesale customers that buy from San Francisco at least a little bit of leverage. But it was only in 2018 that San Francisco agreed to even the 5% cutback, and with the state leaning on the city to substantially reduce its take from the Tuolumne River, its main source of supply, it’s not hard to envision the Bay Area water wars breaking out again.

Nicole Sandkulla, CEO and general manager of the Bay Area Water Supply and Conservation Agency (BAWSCA), which represents San Francisco’s wholesale customers, said that as it gets more difficult for some of SFPUC’s wholesale customers to hit high reduction targets, the question of who takes the brunt of the cutbacks could reemerge.

“In my mind, that’s a source for future negotiations as we continue to see the pressures from the state for greater, greater, greater and greater efficiency,” Sandkulla said.

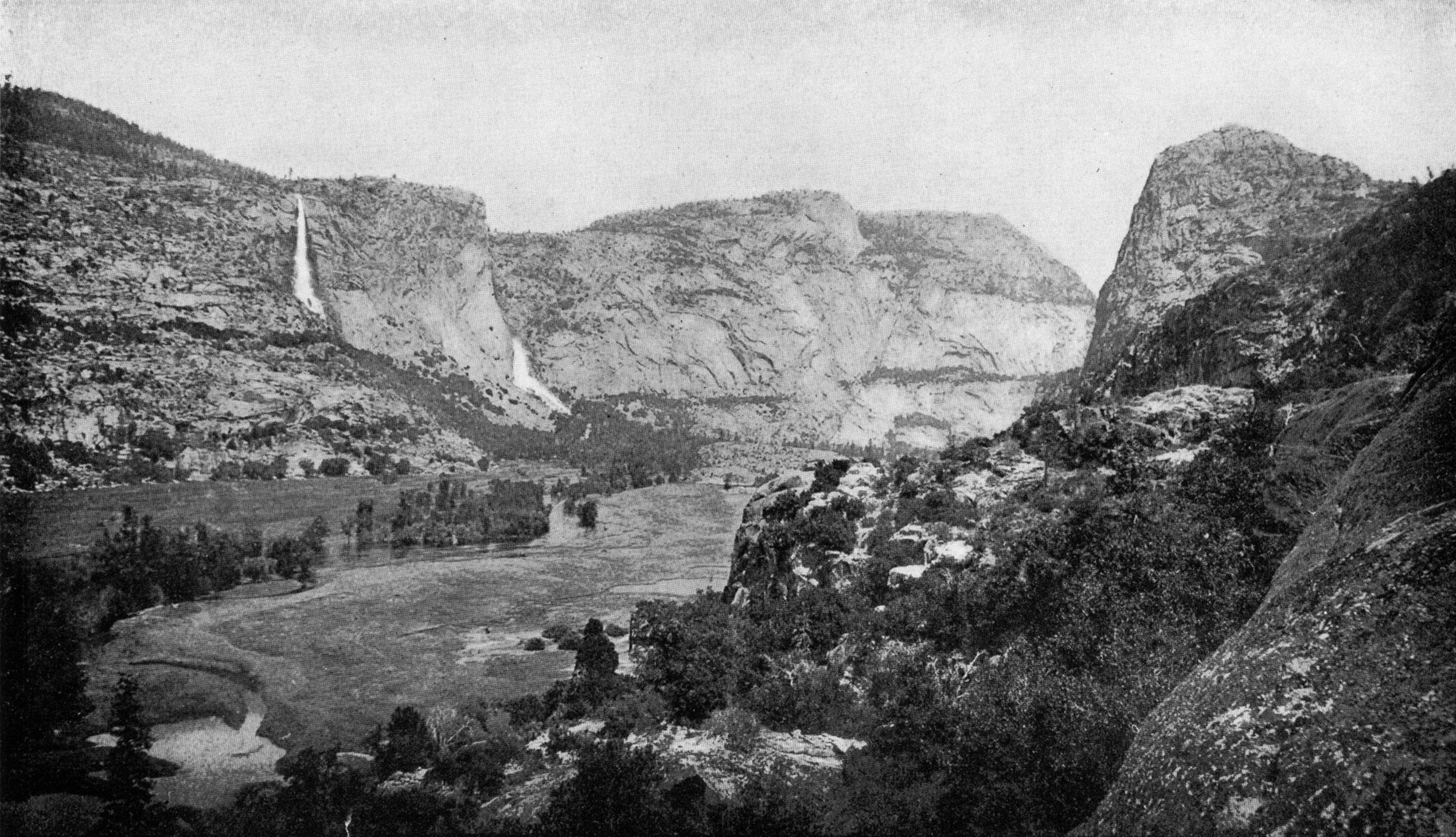

San Francisco’s powerful water position was born in 1913, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Raker Act, handing the city the right to dam and flood the Hetch Hetchy Valley inside Yosemite National Park. In the 1930s, the city purchased the private Spring Valley Water Company, its reservoirs and water infrastructure on the Peninsula. Combining the two, the SFPUC created a robust water network that flows all the way from the Sierra Nevada mountains to the city and serves 2.7 million people—most of whom are not in San Francisco.

Hetch Hetchy has always been controversial: At the time it was built, conservationists including John Muir argued against the “sinful ingenuity (opens in new tab)” of its construction, and environmental groups like the Sierra Club condemn it to this day. Generations of politicians—including many current ones—have also denounced the fact that power from Hetch Hetchy is sold to PG&E rather than directly to the public, as the Raker Act required.

The SFPUC itself, too, has seen its share of scandals. The city department head is appointed by the mayor—now Dennis Herrera after its last general manager, Harlan Kelly, was ousted (opens in new tab) during the corruption scandals that rocked City Hall (opens in new tab). The annual budget for the agency, which also handles sewage in the city, tops $1.4 billion.

There is no doubt that Hetch Hetchy is an exceptional water resource. It lies in a snow-heavy band of the Sierras, and thus gets more run-off than the more northerly Shasta, Trinity and Oroville reservoirs, which serve big state and federal water projects and are heavily depleted. The system also has massive storage capacity, and its northern California customers are lighter users of water compared to those in Southern California, where much of the state’s water ultimately goes.

And because the city’s Hetchy Hetchy water rights predate the state’s formation of the Water Resources Control Board in 1914, San Francisco is the last to have to reduce its water usage in times of crisis.

“The water supply conditions are really distinctly better for us than they are for the State Water Project and the Central Valley Project reservoirs up in the north state—Lake Shasta, Lake Oroville—those reservoirs are kind of hurting,” said Steve Ritchie, SFPUC’s assistant general manager for water. “Because we are so reliable, people have turned to us as their only reliable source during time of drought.”

The crisis is so big that last month, the state banned water agencies from pulling any more water from rivers (opens in new tab) this year. But San Franciscans wouldn’t know.

With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

By controlling the water source and infrastructure, San Francisco has historically set the terms of who gets what and when.

Neighboring water users have chipped away at the city’s dominant position over the years. A lawsuit in the 1970s (opens in new tab) resulted in a settlement that lays out just how much water various customers are guaranteed each year. BAWSCA was formed in 2003 to represent the jurisdictions that buy wholesale from San Francisco, and that collectively sent $300 million to the city for water just last year. In 2009, the agency negotiated a new 25-year water supply agreement on the wholesale customers’ behalf and subsequent amendments, including one in 2013 (opens in new tab) to give the wholesale customers a say on any potential changes to the Hetch Hetchy system.

In 2018, the agency helped negotiate an amendment to the regional contract to, for the first time, require San Franciscans to make at least 5% cutbacks during drought.

But a bigger threat to San Franciscans’ water security may come from the state. In 2018, in response to growing drought conditions and concerns about the ecological impacts of San Francisco’s near-monopoly on the Tuolumne River, the state rewrote the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan, the state’s regional strategy for water control, with a new goal to leave 30% to 50% of the flow of the San Joaquin, Tuolumne, Merced and Stanislaus Rivers untouched between February and June to benefit the rivers’ watersheds and salmon population.

That would reduce the city’s share of the Tuolumne’s flow into Hetch Hetchy and its other reservoirs—which can top 90% in dry years—to closer to 60%.

But the plan has yet to be implemented as the SFPUC and BAWSCA together brought a lawsuit (opens in new tab) against the state arguing that 60% isn’t enough to support the region’s water needs (opens in new tab). Instead, the state and regional water agencies are negotiating on “Voluntary Agreements (opens in new tab)” that dole out less dramatic cutbacks to the city’s supply.

And San Francisco continues to push back against across-the-board cuts for city residents using its low per-capita water usage as a bargaining chip.

“That’s the way we’ll continue to do this,” Ritchie said. “And we’ll just be very, very clear with the state that that’s the way it works.”

Even as the state tries to put the squeeze on, many jurisdictions are looking to diversify their water sources by using more groundwater, recycled water or buying from new suppliers. For example, Alameda County Water District, which serves Fremont, Newark and Union City, may now look to up its share from San Francisco from the typical 20% as it faces massive cuts from the State Water Project and contamination in its groundwater.

Wholesale cities and agencies might not always be able to up their shares during drought, Sandkulla said, but San Francisco is required by contract to keep delivering to its existing customers.

Correction: This story has been corrected to show that the SFPUC does not sell to agricultural customers.