In a city with thousands of homeless people and only hundreds of places designated to house them, deciding who gets to live in the units is no easy task.

That’s why the so-called coordinated entry system is so critical: it’s the arbiter of who among the city’s 8,000 homeless is assigned to the 800 or so units available by a 2022 count (opens in new tab).

The city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, which runs the unit, calls it the “front door” of its homelessness response programs.

Here’s why it matters to San Francisco.

What is coordinated entry?

With demand far outstripping supply, it’s essentially a form of triage.

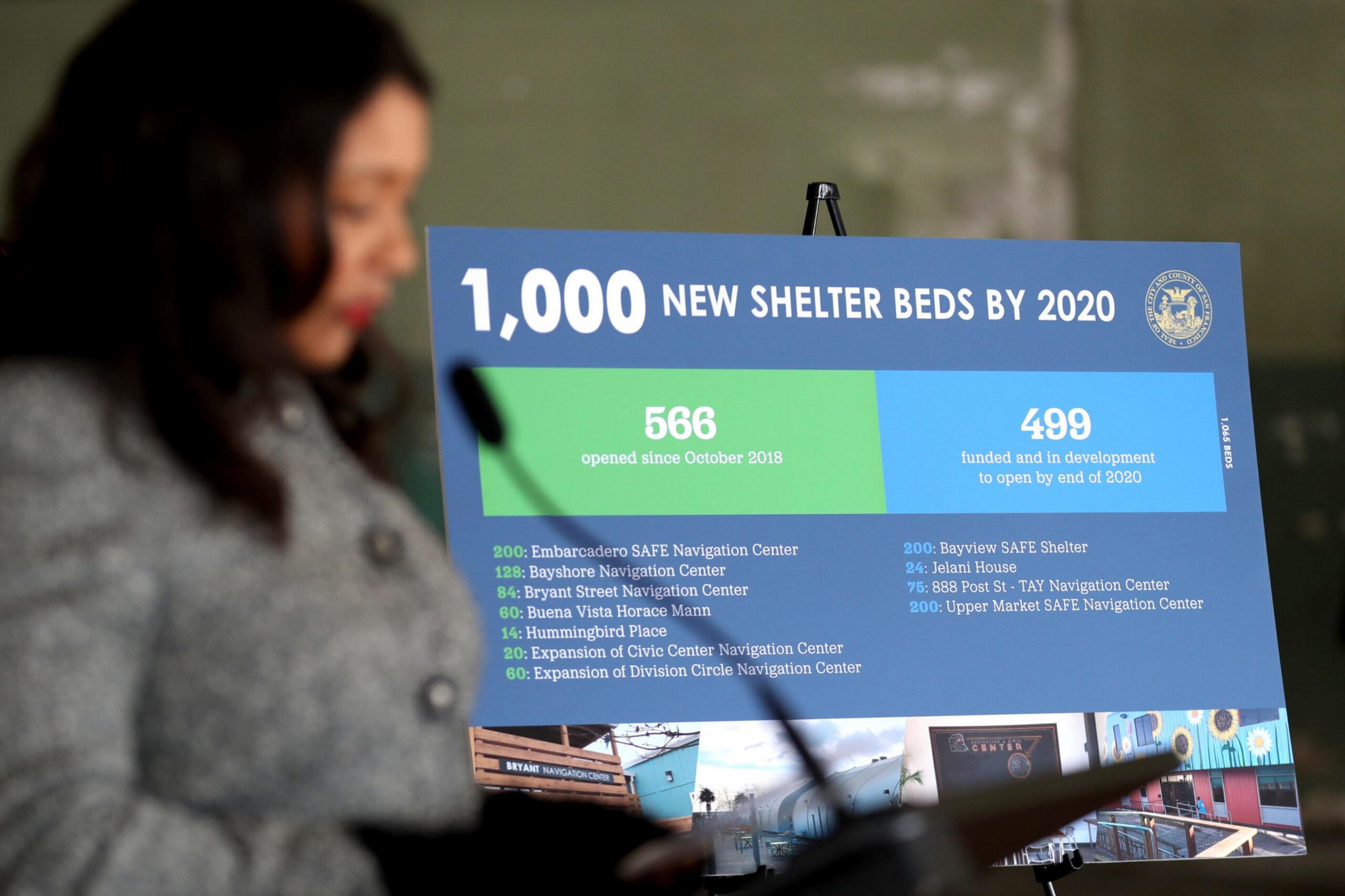

A 2022 count put the number of unhoused people in the city at 8,000, with about half sleeping on the streets on a given night. And sure, Mayor London Breed has overseen substantial investments into the city’s permanent supportive housing stock—with the city contracting 2,573 units since July 2020 and recently purchasing a 200-unit building on 12th Street for $145 million. But those investments still fall short of need and, according to a recent poll by The Standard, residents continue to cite homelessness as a top concern.

Coordinated entry stands between a mounting crisis and a byzantine bureaucracy.

Homeless people looking for help in San Francisco get steered to coordinated entry either through a nonprofit-run “access-point (opens in new tab)” or by engaging with the city’s homeless outreach teams. Then, they take a survey, which evaluates needs based on each client’s history of homelessness, barriers to housing and vulnerability.

Factors such as income, parenthood, substance use disorders, criminal records, and history of trauma help the city decide what kind of help a person gets. Officials say clients aren’t usually told ahead of time how their answers affect eligibility for services.

As part of the city’s coordinated entry system, homeless outreach teams accompany what’s known as the Healthy Streets Operation Center to move unsheltered people from sidewalks into shelters—with the stated purpose of eventually placing them into permanent housing. These “encampment resolutions,” as the city calls them, can trigger a coordinated entry assessment of each involved individual, placing them on a waiting list for permanent housing, shelters or other services based on the severity of their case.

Once initiated into San Francisco’s homelessness response system, unhoused people are required to visit one of the city’s access points to continue with coordinated entry. If a person isn’t able to report what’s preventing them from accessing services, or if they’re deemed unqualified by an initial assessment, the city may begin a “clinical review (opens in new tab)” of the person’s record to consider how to help them on a case-by-case basis.

Who runs coordinated entry?

The San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing oversees the coordinated entry system in collaboration with the Homeless Outreach Team and a constellation of nonprofits that operate the program’s access points.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development requires that counties implement such systems to ensure standardized decision-making in how federal money gets distributed to local homeless services.

The feds also require local governments to prioritize housing and supportive services for the most vulnerable homeless clients. But the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing comes up with the metrics to determine need.

In San Francisco, a person’s eligibility and needs differ depending on age, military status, and whether or not they have dependents. Officials say the city has more resources for homeless families, making it more likely that homeless people with children will secure housing through coordinated entry than their single counterparts.

What are the pitfalls?

Homeless advocates have criticized coordinated entry as a process that overlooks people who only appear less vulnerable—perhaps because they’re uncomfortable divulging trauma to city workers. The process turns a self-reported survey into a citywide waitlist that prioritizes people based on their responses to probing questions such as: Have you ever been sexually assaulted while experiencing homelessness?

Advocates also say the system is overly confusing.

Only a third of single adults and about a fifth of homeless families or youth are connected to housing through coordinated entry, according to a report by the San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness (opens in new tab).

Why should I care?

In a poll of San Francisco voters commissioned by The Standard, 68% of respondents cited homelessness as the biggest problem with city life. Another 70% cited homelessness as a top reason to move out of San Francisco.

San Francisco also likes to call itself a housing-first city—that is, one which invests in permanent housing as the primary tool for addressing homelessness. But the city’s approach is not without controversy. Some groups and politicians say San Francisco should also build temporary shelters to get people off the streets more quickly.

Whether a homeless person finds short-term shelter or ends up in long-term housing in San Francisco, coordinated entry marks a first step.