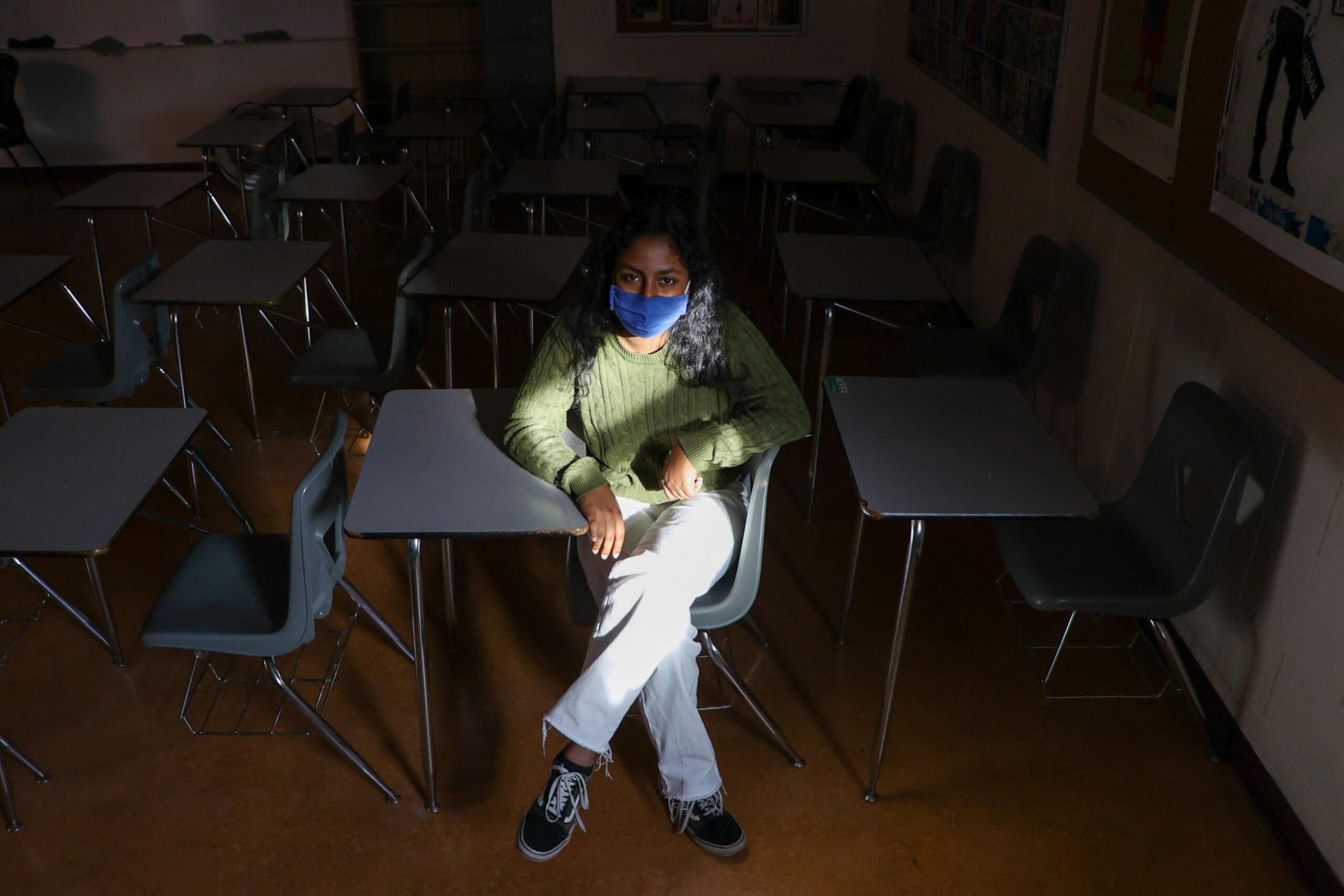

Sitting in her AP World History classroom, its sole window propped open to ventilate the room, Rhea Iyer is acutely aware that she is living in historic times. Undaunted, she is taking the challenge head-on.

With Omicron surging throughout the San Francisco Unified School District, Iyer, a senior at Lowell High School and president of the district’s Student Advisory Council, is doing her part to get the adults in charge to listen to the serious concerns that she and her classmates have—and, more importantly, to actually address them.

“We want more action a lot faster from the district,” Iyer said. “We don’t think students are being considered in the policymaking process or even in the discussions.”

Tensions are high as the latest and most contagious variant of Covid sweeps through San Francisco’s public schools. More than 2,800 students and staff have tested positive for the virus in the last 2 1/2 weeks alone—by far, the biggest spike local schools have seen since reopening in-person learning last spring. The return to classrooms after winter break came just as Omicron was gaining steam in San Francisco. The resultant rise in infections has hit younger demographics harder (opens in new tab) than any previous surge, and students like Iyer are weighing the risk of putting themselves, and by extension their families, in harm’s way for the good of their education.

“It just made everything a lot more stressful.” Iyer said.

For some, like Lowell junior Cal Kinoshita, the risk of in-person learning simply isn’t worth it. He had been home for more than a week when he spoke with The Standard, and said while he is worried about falling behind in his classes just as grades matter most for college applications, his fear of passing on the virus to high-risk people is even greater.

“We, my parents, don’t really feel comfortable given the surge, because we do have vulnerable family members,” Kinoshita said, adding that his parents aren’t convinced his school can keep him safe. “They’re just really disappointed with the district’s safety protocol.”

Other students are more worried about missing in-person school and falling even further behind. At John O’Connell High School in the Mission District, head counselor Pete Wolfgram is in triage mode, working overtime to help students missing class because of Covid, exposure notifications or fear of the virus. Some days, Wolfgram said, it feels like half of his students are absent.

“Students are just stressed out in general,” Wolfgram said. “They’re stressed about Covid, they’re stressed about families going through it. … We’re just trying to stay afloat.”

Iyer and Wolfgram each said their school’s Wellness Centers have been overwhelmed with student requests for help, and a poll of more than 3,000 students conducted by the Student Advisory Council—a panel of students who represent their classmates to the district and includes Iyer and Kinoshita—found that 80% of students have gotten a message about having been in close contact with a positive Covid case. That’s on top of a student attendance rate of 83% the first week back from winter break, down significantly from the 95% norm, which has left classrooms feeling unusually empty.

“It was kind of jarring at first when I came to school after winter break and there were so few people here,” Iyer said.

The poll was part of a district-wide student survey and letter (opens in new tab) that Kinoshita, Iyer and fellow SAC leader Joanna Lam authored to gauge student concerns and feelings about school safety during Omicron. Presenting to the Board of Education last Tuesday, student delegates Lam and Agnes Liang—both of whom stayed home from school last week—called in to demand action. Lam and Liang said the survey results show students are split on whether they’d prefer to be in-person or remote, a trend Wolfgram also sees among his students.

“Some people are very scared of going back online, and that’s really valid,” Lam said at the meeting. “Some people are really scared to go to school, and that’s also very valid.”

But student leaders on both sides of the issue say that they and their peers should have more of a voice in making school a safe place to learn. More than three-quarters of surveyed students agreed that they should be offered a remote learning option for at least the next few weeks to accommodate everyone staying home—whether they have tested positive for Covid, been in close contact with a positive case or simply because they feel unsafe.

Included in the letter are four more demands of the district: Direct Covid-related communication to students via email and posters; excused absences for students staying home out of fear of the virus; greater clarity on test, mask and other hygiene resource distribution; improved enforcement of masking and distancing at schools; and required vaccinations for school attendees.

Immediately after returning from winter break, student leaders worked overtime on the weekends to roll out the survey and draft the letter to call attention to what it’s been like going to school during Omicron. For Kinoshita, who called current conversations about the disease’s severity “dangerously dismissive rhetoric,” it’s been important to focus on the unique threat of the surge on his classmates who live in multigenerational households or are at higher risk of the more damaging effects of contracting Covid.

“Those students shouldn’t be forced to choose between potentially setting themselves up for failure for the rest of the semester or protecting a relative,” Kinoshita said.

That exact concern is shared by Danielle Roubinov, a licensed clinical psychologist at University of California San Francisco who studies how early exposure to adversity and trauma shapes kids’ health and development trajectories. Her biggest worry is on behalf of kids and families for whom Omicron is still dangerous, like those with underlying conditions.

“I worry about the refrain of things being mild and that leading to not enough attention or protections for those children and families who might still be very vulnerable,” Roubinov said.

In response to the Student Advisory Council letter, SFUSD Superintendent Vince Matthews promised to meet with students to hear their concerns. He came to this week’s board meeting with updates on improving communication and making test and mask distribution more transparent. The temporary remote learning option students have been calling for does exist, Matthews said at Tuesday’s meeting, but there are limitations on which students qualify and how many can enroll at once. And while absences aren’t automatically excused for students staying home out of fear, Matthews said parents can call or write in to excuse students.

Kinoshita said he, too, is disappointed in how slow the district has been to respond to student demands. But he is heartened by the support that teacher and parent groups have shown for student concerns.

“It’s really good to see teachers and students—the people in schools—coming together to tell the district that it’s not good enough,” Kinoshita said.