Radio DJ Harrison Chastang remembers a time when the Fillmore District was alive with dozens of Black-owned bars and jazz clubs.

“There was this restaurant, called 1300 Fillmore, that was opened right around the time Obama was inaugurated. It was the spot to hang out,” Chastang said. “If you wanted to run into African American movers and shakers, that was the place to be.”

“Anybody from like Willie, Kamala,” Chastang says, mentioning acquaintances like the former San Francisco mayor and current vice president of the United States. “Anybody who was anybody in SF one time or another popped on in.”

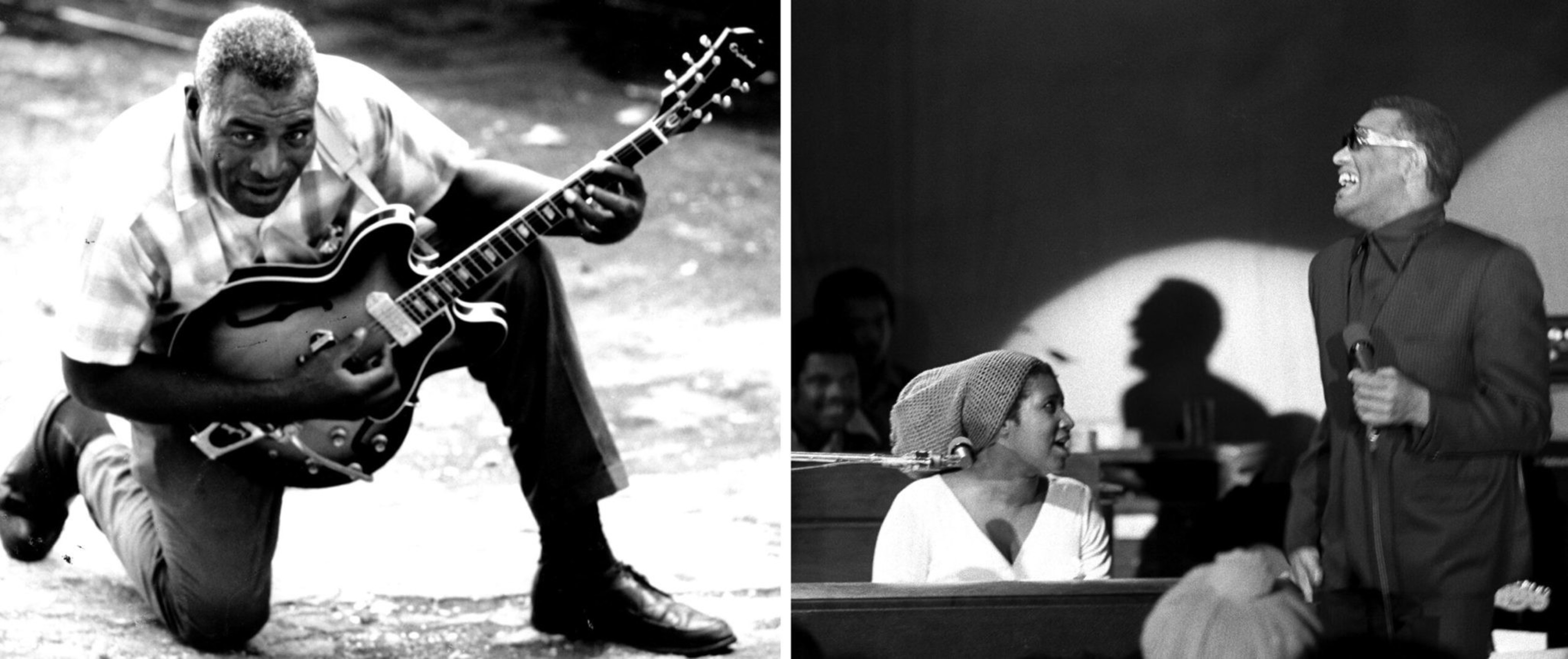

The Fillmore was the “Harlem of the West,” a central hub for Black San Francisco that produced local politicians like Mayor London Breed and hosted a slew of giants in the entertainment industry. Chastang, who runs a jazz show on KPOO, remembers meeting legends like George Clinton and Elvin Jones—funk and jazz innovators who used to play sets at any one of the Western Addition’s 29 jazz clubs (opens in new tab).

“You walked the streets looking for parties,” former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown says in the 2001 PBS documentary The Fillmore (opens in new tab), comparing the district’s heyday to the Harlem Renaissance. “That was what Fillmore Street was like in those days.”

Today, just two jazz clubs remain on Fillmore Street. Decades of redevelopment and gentrification have all but decimated Black spaces in the neighborhood, pushing thousands of residents out and setting up tense battles over the district’s soul. In spite of City Hall’s attempts to redress these historic, systemic wrongs, recent efforts to revitalize existing Black community spaces have floundered.

No venue embodies the neighborhood’s woes better than the Fillmore Heritage Center (opens in new tab), which has faced a revolving door of tenants, owners and entertainment programs since its 2007 opening (opens in new tab). One by one, clubs and restaurants at the heritage center have closed (opens in new tab), leaving a 50,000-square-foot hole in the heart of San Francisco’s historically Black neighborhood at exactly the time when the city has begun to consider in earnest what it owes its Black residents.

A ‘Multimillion-Dollar Blight’

The Fillmore Heritage Center was one of the last projects carried out by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency and was designed to honor the neighborhood’s rich history and to draw consumers from outside the region.

For a few years, that’s exactly what it did: Original tenants included famed Oakland-based jazz club Yoshi’s San Francisco and the music lounge at 1300 Fillmore St. But by 2014, Yoshi’s declared bankruptcy and closed. Less than a year later, its replacement—a jazz club called The Addition—also shuttered due to financial hardship, and by 2018, the last holdout at 1300 Fillmore was gone.

The massive concrete center cost a whopping $80.5 million to construct, only for every business inside to disappear within years. Observers have now branded the massive space as the neighborhood’s “multimillion-dollar blight (opens in new tab),” a physical reminder of the city’s inability to steward Black social and political life in San Francisco.

“The Fillmore Heritage Center is about the history of the community, but it’s also about being an important clearinghouse for the various issues and needs that face the community,” said James Taylor, a professor and scholar of Black history and politics at the University of San Francisco.

Today, the center’s windows are adorned with images of Fillmore’s jazz and civil rights legends—at the same time that it sits under a high-rise of luxury condos (opens in new tab) in a neighborhood historically and presently struggling with the pressures of gentrification and displacement. Though some tenants have reactivated the center (opens in new tab) for brief stints since 2018, none have established a long-term business or residency in the space.

“The concern Black San Francisco has had all along is about belonging and place around housing and community,” Taylor said. “The Fillmore Heritage Center is the same building where the Black Panther paper was published. […] It’s where a significant political history was achieved and realized.”

Frayed Trust and Broken Promises

It’s tempting to look at the Heritage Center’s short history and come up with straightforward explanations for its chronic closures, such as poor business planning by previous ownership. But it’s much more complicated than that, and community members say those excuses gloss over decades of broken promises and negligence exhibited by past and present city representatives.

A brief history lesson: Between 1935 and 1945, San Francisco’s Black population swelled to roughly 30,000 people (opens in new tab)—a 600% increase that attracted businesses and nightlife. But the Fillmore was a vibrant cultural nexus for just a few years before the city’s urban renewal program (opens in new tab) all but decimated the neighborhood after 1950. Under the banner of “redevelopment,” city leaders leveled 883 businesses, including nearly all the neighborhood’s jazz clubs, and displaced 4,729 households from Western Addition.

“The absence of the community, and the dispersal of the community is often the explanation for why [the Fillmore Heritage Center] can’t be supported,” Taylor said.

More recently, as high-paid tech workers flood into Hayes Valley and Western Addition, residents say real estate prices have risen so high that it’s become nearly impossible to live or consider moving into the Fillmore.

The housing crisis has grown so intense that, in recent months, legislators have proposed a bill (opens in new tab) to replace the thousands of affordable housing units lost during San Francisco’s “urban renewal” period in the Western Addition.

“[The city] is trying to revitalize it, not only for African Americans but so everyone can have the chance to use the Fillmore center,” said longtime SF resident Vanessa Matthews. “It’s really hard now, because the real estate prices are going up and businesses are gradually declining. You might see a business open, and maybe six to seven months later, it’s gone.”

Saving the Center and the Community

It’s not just historic examples of redevelopment; recent controversies at the center raised questions about City Hall’s present-day commitments to supporting Black-owned businesses in the Fillmore. The recent timeline of the Fillmore Heritage Center reveals numerous spats between city departments and local community leaders.

After The Addition closed in 2015, just three months into its operations, the City Attorney’s Office sued its owner (opens in new tab) and developer Michael Johnson over allegedly unpaid federal loans. When gunshots rang out near the center (opens in new tab) in 2018, the city effectively shut it down, refusing to renew the lease to its temporary tenants New Community Leadership Foundation (opens in new tab) and the San Francisco Housing Development Corporation.

Tensions have also risen among local community leaders, who expressed concerns about City Hall’s transparency during previous proposal processes. Foundation spokesperson Majeid Crawford told the SF Business Times (opens in new tab) his group no longer works with the center, and may not pursue the newest request for proposals (RFP), or the document the City of San Francisco posted to solicit bids for the Fillmore Heritage Center.

And Agonafer Shiferaw, the owner of former jazz club Rassela’s (opens in new tab), filed a suit (opens in new tab) against the city in 2021, claiming that Mayor Breed prioritized certain community leaders and political allies in the last proposal process.

“The city should work to ensure that the center becomes an engine of African American prosperity in the Fillmore,” said Shiferaw, who said he made at least four separate offers to buy or fill the center—all of which he says were rejected. “However, the new RFP looks to me like the wish list of a preselected proponent and therefore raises suspicion of fresh corruption and cronyism by city officials.”

The center’s repeated controversies and closures sparked a fierce outcry (opens in new tab) from locals, who ultimately worry that the recent request-for-proposal process won’t result in a community center run by and for Black San Franciscans.

“There’s a lot of animosity and frustration, not just with the city, but with the culture that’s connected to Black community,” said Sheryl Davis, executive director of San Francisco’s Human Rights Commission. “Folks are kind of like, ‘We don’t need you telling us who to use or what to do,’ you know? It’s a hard needle to thread, as they say, to figure out how we connect people.”

‘A Forced Marriage Doomed for Divorce’

The city’s latest request for proposals to fill the center was issued in the hopes that a community-oriented tenant shows up to reactivate the Fillmore center and make it the important economic and commercial opportunity it once was. If that request-for-proposals process sounds familiar, it’s no coincidence: City Hall last asked for plans to fill the center in 2017 (opens in new tab), but it failed to sell the complex or obtain any meaningful leases.

Now, the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development says it is trying a different approach to fill the center—one that involves collaboration from multiple city departments, including the mayor’s housing office, the Human Rights Commission and the Office of Economic and Workforce Development.

The glue connecting the Fillmore to that blur of city agencies is Davis. Though she is not officially part of the request process, her background as a longtime Fillmore resident and her extensive political experience perhaps make Davis the ideal liaison to broker a deal between the city and communities the center is supposed to serve.

“The blend of community and businesses without resources is a forced marriage doomed for divorce,” said Davis, who says that her goal is to mesh innovative community ideas with viable resources from the city.

Though the new request-for-proposals process (opens in new tab) looks almost identical to the previous iteration, City Hall pledged upward of $1 million in support for the center’s operations, with support declining over the following years. New tenants will receive at least five years of operational support, including a five-year lease term with the option for an extension.

Davis and City Hall say the new plan is designed to disrupt the center’s high turnover rates and previous financial issues, creating a long-term vision for the space. But the city’s focus on financial responsibility and longevity is no accident.

“I think that the challenge here is—how do we not lose the soul of the Fillmore, while at the same time leveraging people who, when you’re in lean years, can keep it going?” Davis said.

The Last Jazz Restaurant in the Fillmore

Today, Sheba Piano Lounge is one of the few Black-owned restaurants that still hosts live jazz shows from the Fillmore District—and it’s allegedly one of Mayor Breed’s favorite Friday night spots. But co-owner Netsanet Alemayehu has watched as nearby clubs and bars quietly shuttered, letting the once-lively segment of Fillmore Street fall silent.

“Before the redevelopment agency, this was a hub—all the famous musicians played here; there were a lot of Asian businesses,” Alemayehu said. “The fact that [the city] invested in this area, and we are the only one that survived […] they should support us, but they don’t.”

The Fillmore District’s commercial and community struggles have raised questions about the city’s inability to revitalize the neighborhood, and how the center symbolizes ongoing debates about reparations. In 2021, for example, community leaders including Amos Brown and actor Danny Glover rallied on the steps of the center, calling for it to be returned to the hands of the Black community.

“Reparations is the last thing that America can do—young America has no great future unless it does reparations,” Taylor said. “Everything the Black movement has ever done over the last 150 years has been toward reparations.”

READ MORE: Black Leaders Call on City To Donate Fillmore Heritage Center

Ultimately, concerns about the request for proposals reflect the complex history that swirls around the Fillmore Heritage Center. Nobody wants to see this glorious event space empty—but from historic injustices like urban renewal to the present-day legal battles fought on the center’s steps, it’s hard to imagine a future in which the center is full of life.

But the Fillmore District and its cultural scene are not dead. At Sheba Piano Lounge, Alemayehu and her sister still host jazz musicians five nights a week, and local programs like In the Black continue to attract small Black-owned businesses to the area. The Fillmore Jazz Festival will bring legendary musicians to Western Addition in July, and the conversation surrounding reparations is heating up among city supervisors.

“Just from an economic development perspective and investment in the community, [the center] needs to be activated—it’s fully consistent with the idea of reparations,” said Supervisor Dean Preston, whose district includes part of the Fillmore. “Even for folks who may not fully be on board with reparations, they should not hesitate for a second to have the city move forward with this process of activating the center.”

WATCH: Powerful Moments From San Francisco’s First Big Reparations Meeting

The fate of the Fillmore Heritage Center will remain in limbo until April 24, when the request for proposals reaches its deadline. The RFP committee will review entries, host town hall meetings with community members and hopefully find a winning proposal—and a future for the symbolic center of Black San Francisco.

“The Heritage Center […] stands to lose in a similar way that the Black community of Harlem, New York, lost in the ’70s when they failed to secure a singular building that was far more important than the facility itself,” Taylor said. “It was about the psychological, the spiritual, the cultural and physical meaning of being Black in those communities.”