If you walk past the tchotchke shops on Fisherman’s Wharf, past the string of crab stands permanently closed by the pandemic, past the whirs and clangs of the antique penny arcade machines of the Musée Mécanique (opens in new tab) and the restored World War II-era submarine USS Pampanito docked on Pier 45—what you’ll see is a whole lot of nothing.

In May 2020, a massive inferno (opens in new tab) burned down a warehouse that stood at the edge of the pier, destroying millions of dollars worth of fishing equipment. Attorneys struck a $6.2 million settlement earlier this year, but those impacted said they’ve yet to see any payments.

During a recent afternoon on the cracked concrete, with Alcatraz as a backdrop and the salty scent of the bay and stale seafood in the air, Chris McGarry pitched a dream for what’s possible at the empty site.

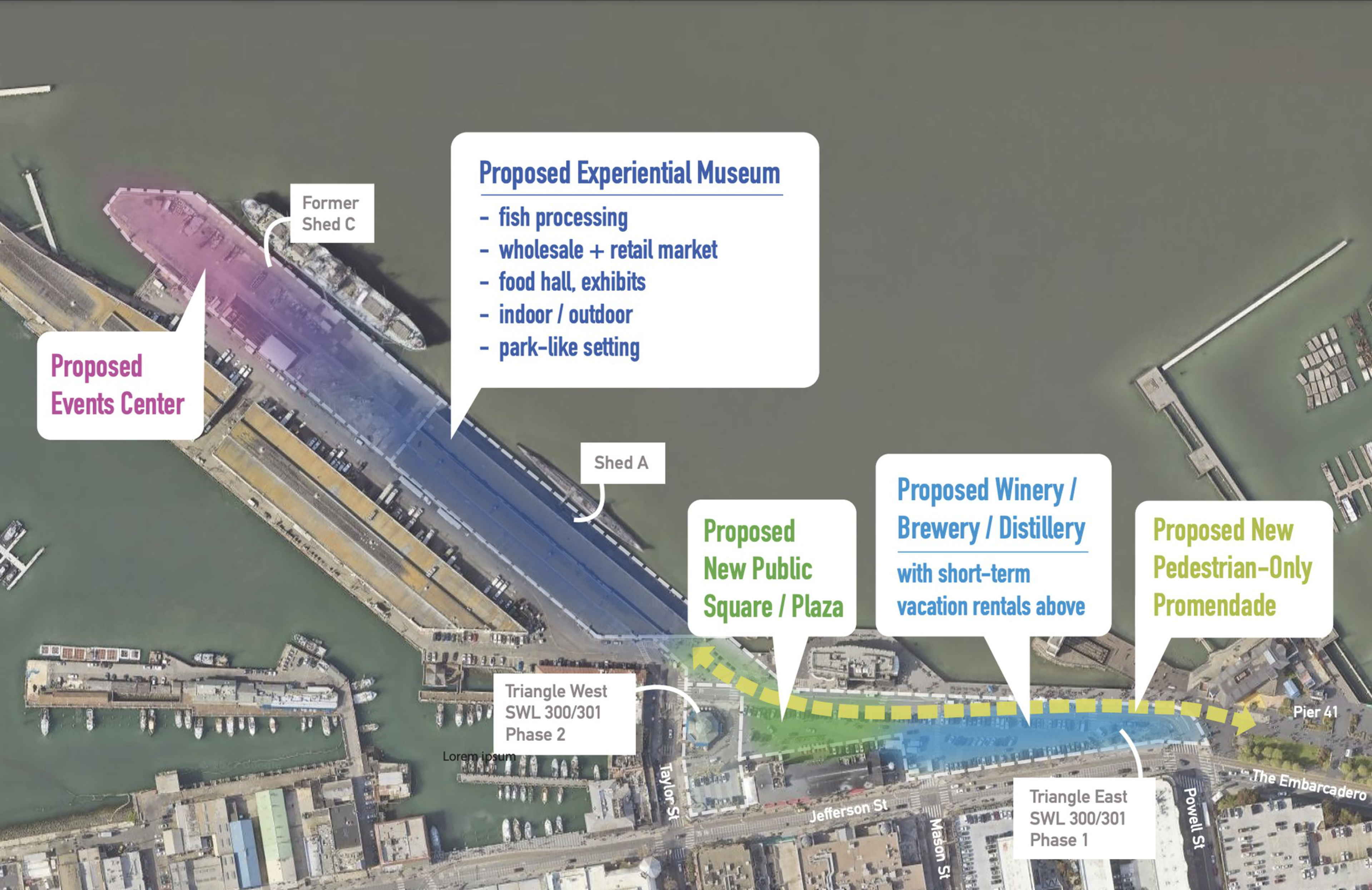

Instead of a makeshift parking lot, McGarry said, imagine an “experiential museum” that celebrated the history of the wharf, a wholesale seafood market, a viewing area to see workers expertly fileting fresh catch and a food hall selling the seafood prepared in a variety of ways. What about an events space to host corporate events, concerts, even weddings? Or vacation rentals atop a brewery and winery?

“Part of it is going to be a treasure hunt. You never know what you’re going to find, but you know it’s going to be a reliable destination,” said McGarry, the former CEO of Save Mart Supermarkets. “It’s moving past the dream stage into a vision.”

Pier 45 is at the center of McGarry’s vision (opens in new tab) for the first large-scale redevelopment of the area in decades, with the goal of ushering the languishing destination into a new era at an expected cost in the tens of millions. Visitor numbers to Fisherman’s Wharf are starting to recover from the depths of the pandemic, but are still around 20% below the 16 million people who used to visit annually.

McGarry is part of a team calling itself Fisherman’s Wharf Revitalized seeking to redevelop the Port-owned property. The plan is the brainchild of Lou Giraudo, a well-connected San Francisco businessman and attorney whose family owns Boudin Bakery, a major anchor business at the wharf.

Other partners include Dante Serafini, the owner of the Franciscan Crab Restaurant, and Seth Hamalian, a developer who helped lead the transformation of Mission Bay into a life science and medicine hub.

The plan was submitted unsolicited to the Port of San Francisco, a rarity although not entirely uncommon for unique projects. At a Port Commission (opens in new tab) meeting Tuesday, the plan received early, positive comments from commissioners, although there were pointed questions about the lack of a competitive bidding process. Mirroring broader concerns with the plan, one of the main themes of the community feedback was a desire to keep the area as a working fishing wharf.

Giraudo cautioned that the Fisherman’s Wharf proposal is still in an early stage, but said he’s been in conversations with financial institutions who can back the project.

If the plan were ultimately approved by the Board of Supervisors, the team could finalize design and construction in five to six years, though that timeline could change. The final budget is still in flux, but the project would need additional financial support from the port to get past the finish line.

Most everyone—from the still-active commercial fishermen and the remaining restaurants to port commissioners and the developers themselves—agree that the wharf is in need of fresh blood. The pandemic exacerbated years of disinvestment, leading to vacant storefronts, increasing blight and a distinct feeling of a neighborhood in decline.

Even tourists have taken notice. German traveler Soely Schmidt glumly took a drag from a cigarette in front of the shuttered Pompei’s Grotto restaurant on Jefferson Street.

“I thought Fisherman’s Wharf would be less souvenir shops,” she said, holding up a plastic bag from one of the nearby vendors selling T-shirts and novelty magnets. “I thought it would be more authentic in a way.”

Although tourists and locals alike find the wharf’s current state less than thrilling, turning an ambitious idea into reality is easier said than done—especially in San Francisco, where it’s notoriously difficult to build anything. The development team has already bumped up against factions skeptical of the premise that the area must transform to survive.

A Living History

Ironically, particularly to locals who consider it a tourist trap, there’s still a blue-collar spirit that exists on the wharf—one often measured in generations rather than years.

“Any investment in the wharf certainly can’t hurt, that’s for damn sure,” said Randall Scott, the executive director of the Fisherman’s Wharf Community Benefit District. But he said he wants to ensure that those who helped build the wharf aren’t left behind in a rush to modernize.

Some of the strongest pushback against the plan to redevelop Pier 45 has come from the few dozen commercial fishermen still working the wharf. After the destruction of Shed C in 2020, much of their gear storage has now moved to the adjacent Shed A.

The development plan wants to take over a portion of the space for a museum meant to celebrate maritime history, which could potentially require moving the gear to a yet-to-be-determined location. That leaves many fishermen asking whether the plan relegates their way of life to the past.

“I don’t personally see the coexistence of tourism and commercial fishing in the same place,” said John Barnett, president of the San Francisco Crab Boat Owners Association. “You want to romanticize the lifestyle, but romance is someone else’s hard work.”

Barnett said he’s been burned with empty promises before. And he’s not sure most people would really want to see an unvarnished version of their industry, certainly not as a backdrop to a wedding or birthday brunch.

A number of commercial fishermen said that cutting off easy access to their gear would mean leaving San Francisco for Bodega Bay or Half Moon Bay. The development team has weighed potential solutions, including the construction of new facilities and infrastructure somewhere else along the waterfront to help load gear on and off their boats.

Giraudo said he’s confident the developers could work out a system to preserve the fishermens’ ability to work while creating new attractions.

Holly Fruehling, who wears her status as San Francisco’s first female crab captain proudly, is more sanguine. She stressed the wharf’s need for new investment and believes Giraudo’s team has the ability to follow through, though she echoed other concerns around parking and vehicle access; the plan would involve creating a pedestrian-friendly zone with vehicle use restricted.

Fruehling was one of the first participants in a program that allowed fishermen to sell catch directly off their boats (opens in new tab) and would regularly sell out before noon, mostly to locals. That’s a sign of pent-up interest, she said.

“If it’s going to be a working wharf, then parts of it are going to be a working wharf, which means you have fish parts and you have trucks and you have smells,” Fruehling said with a chuckle. “I think everything’s a balance. You can still have your fancy stuff, but still keep a little bit of the history.”

One question from fishermen and current tenants is why investors can’t simply improve existing structures and businesses. Giraudo argues it’s a matter of dollars and cents: The project needs to pencil out to attract the investment necessary to shore up the sea wall and build up infrastructure resilient to climate change concerns.

“We’re saying to them: We want to work with you to rebuild this pier, and we want to put in these new things to pay for what needs to be done,” Giraudo said. “These attractions could be the economic engine to make it possible.”

‘We’re in Crisis’

Skeptics also wonder why Giraudo even wants to undertake such a project. Is it self-importance, personal financial benefit, a sense of civic responsibility, perhaps some mix of all three?

“Some people say it’s an ego trip, or it’s this or that,” Giraudo said. “OK, well, I’m 77 years old. Am I going to make a fortune? For what?”

Giraudo and his supporters point out that he’s a San Francisco native son who grew up in and along the waterfront—and who also has the political and financial juice to make the plan happen.

Giraudo has successfully walked the tightrope of San Francisco politics before, having helped influence the construction of the Chase Center in Mission Bay. He was also brought in as an outside mediator (opens in new tab) to work out a deal for development of the $2.1 billion California Pacific Medical Center hospital on Van Ness.

“It has to happen,” Giraudo said. “We’re in crisis. The city is in crisis. Somebody’s gotta do it.”

According to Giraudo, Board of Supervisors President Aaron Peskin, a longtime associate of his, has “promised to be the champion” for the project if the team is able to navigate it through initial hurdles.

In an interview, Peskin said he aims to introduce legislation to pursue exclusive negotiations with the partners, saying their plan highlights the authentic parts of the wharf while addressing the area’s crumbling infrastructure.

He contrasted Giraudo’s plan with previous failed redevelopment efforts like the one from Cleveland developer Malrite (opens in new tab) to build a schlocky entertainment complex and museum on Pier 45 complete with a replica Golden Gate Bridge and fake fog.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Fisherman’s Wharf that obviously is going to require the port to put some skin in the game to make it viable,” Peskin said. “I know that people are always leery of change, but I think it would breathe another century into that way of life while also creating an anchor to attract all sorts of folks.”

Whose Legacy?

Don McFarland has been at Sabella & LaTorre for a quarter-century and now serves as its general manager. The seafood restaurant and bar opened in 1927 and is one of the handful of businesses left after the pandemic hollowed out the wharf’s row of crab and chowder stands on Taylor Street.

Alioto’s, the historic two-story restaurant next door, just missed the century mark before closing forever in 2020. After a lengthy negotiation, the port struck a deal (opens in new tab) with the business owner to end its lease early.

Multiple sources confirmed that negotiations for early lease terminations or lease buyouts are in the works for a number of the wharf’s restaurant tenants. The boundaries of Fisherman’s Wharf Revitalized’s redevelopment plans pointedly end immediately next to the crab stands, but McFarland sees the writing on the wall.

“I think they want to condemn it and then all of a sudden fix it because no one’s left,” McFarland said.

As evidence of city neglect, McFarland points to a proliferation of street vendors that he said have begun brazenly selling alcohol and cannabis without a license.

“I’m all for capitalism, but I just want to be left alone. This is my livelihood, and I’ve been here basically my whole life,” McFarland said, mentioning his restaurant has 13 years left on its lease.

Giraudo has listened to the naysayers and, in some cases, chirped back at them in public outreach forums and informal meetings.

“I’m not saying, ‘Can we take it over and exploit it?’ I’m saying ‘Can we preserve it and make it more interesting?’” Giraudo said. “We’re grassroots. We’re here. It’s legacy for us.”

However, legacy is a complicated concept: Who chooses what’s remembered and preserved versus what’s left behind?

As Paul Capurro, the owner of Capurro’s Restaurant on the far end of Jefferson Street readies for retirement, he considers his own legacy with some sadness when he thinks about the current state of the wharf.

“They handed us a diamond, and we turned it back into a piece of coal,” Capurro said ruefully.

Capurro is organizing a group that can represent the historic Fisherman’s Wharf and ensure the members are a part of the future Giraudo is planning. He said the redevelopment plan might be the best and only alternative to a morbid scenario of just waiting for a generation to die out.

“It’s given me a new hope for the fact that I’m not going to be the one that leaves the wharf to perish under my watch,” Capurro said. “I want to revive it. I want to make it exciting and bring it back. Then I can go play golf in peace.”