At 7 a.m. Jan. 12, I am on the south side of 13th Street between Folsom and South Van Ness, looking north across two lanes of surging traffic to a tent encampment on a median strip.

It has rained—hard—in the night, but we are down to a cold drizzle in the pre-sunrise hours.

Rainwater is still flowing down the streets, and it glistens in the headlights.

I didn’t wear gloves and regret it.

The still dark air is moist and heavy, and the scene has that leaden quiet you get in a funeral home waiting for the service to start.

I am under an overpass formed by the Caltrans viaduct that supports the roadbed of U.S. Highway 101. The overpass creates a favorable venue—at least insofar as San Francisco offers one—for those who are living without shelter.

The viaduct, a steel structure the speckled-gray color of an anchovy, covers the median on the north side of the street and provides protection from the rain when it is falling vertically, a protection that diminishes when there is wind.

The median is perhaps 5 inches above the roadbed and provides some elevation over the torrent of water that has flowed down San Francisco streets this winter while the city has been attacked by bomb cyclones and atmospheric rivers.

These modestly favorable conditions have drawn tent encampments to the 13th Street median for many years. Miserable for sure, but less miserable than some other places.

READ MORE: Is San Francisco’s Best Strategy in Homelessness Lawsuit To Lose?

There are more than a dozen—I count 14—structures located on the median this morning.

The word “structures” needs some explanation for it implies a level of rigidity that is missing here. Tents, not 2x4s, are the building blocks of these structures. And yet just calling them tents misses the ingenuity—or desperation—that informs their construction.

The first one—I later learn, perhaps unreliably—was being looked after for someone else by a young man named Marquis Ausby, who has been living rough for years and was asked to keep an eye on the structure by its owner.

But then the owner evidently told somebody at the city that he was leaving his tent, which was enough for city workers to declare it abandoned and begin the dismantlement.

As they begin to take it apart, it becomes clear that the structure is constructed from three different tents swaddled under a monster piece of heavy gauge black plastic that flaps over the top. One corner of the sheet is knotted to a rope tied to one of the viaduct’s supporting steel beams.

The domed tops of the three tents are humped below the tarp like the bones of a shoulder, but it isn’t until the tarp is completely removed that the complexity below is revealed. It is a warren, a burrow, a fox hole, though I couldn’t tell you exactly how the component tents related to one another.

The tents are bulging—a blue fold-up camp chair, a three-shelf bookcase with jars and candles and food stuff. A jumble of running shoes. A black suitcase that might actually be a padded cushion. Buckets, a half-filled plastic jug. Two dozen hot dogs in their clear wrapping, so pink as to be obscene. Dozens of soda cans, most seemingly empty. A candy bag, the wrapper the color of Sani-Flush with cheerful bold yellow and red lettering that could easily spell the words “Jolly Ranchers,” though I can’t quite make it out.

It takes several beefy Department of Public Works (DPW) employees—wearing masks and yellow hazmat vests—to get all the contents into the back of their dump truck. They use a mechanical lift to lower a platform to the ground so they can drag the tent with the biggest bulge onto the lift and raise it until it can be slid and jerked into the truck. They don’t look inside, though I see some details that make me want to stop everything and find out who this tent belongs to and why they are taking it away.

There is a blue hand-painted sign, clearly for use in panhandling. It is a wooden board—not something ripped from a cardboard box—and beautifully designed, that proclaims, “Any Amount Helps (A real) Vet. Experience FREEDOM”. The sign falls from the tent like all the other debris, but it lands painted side up on the sidewalk, ironic commentary on those that “Experience HOMELESSNESS.”

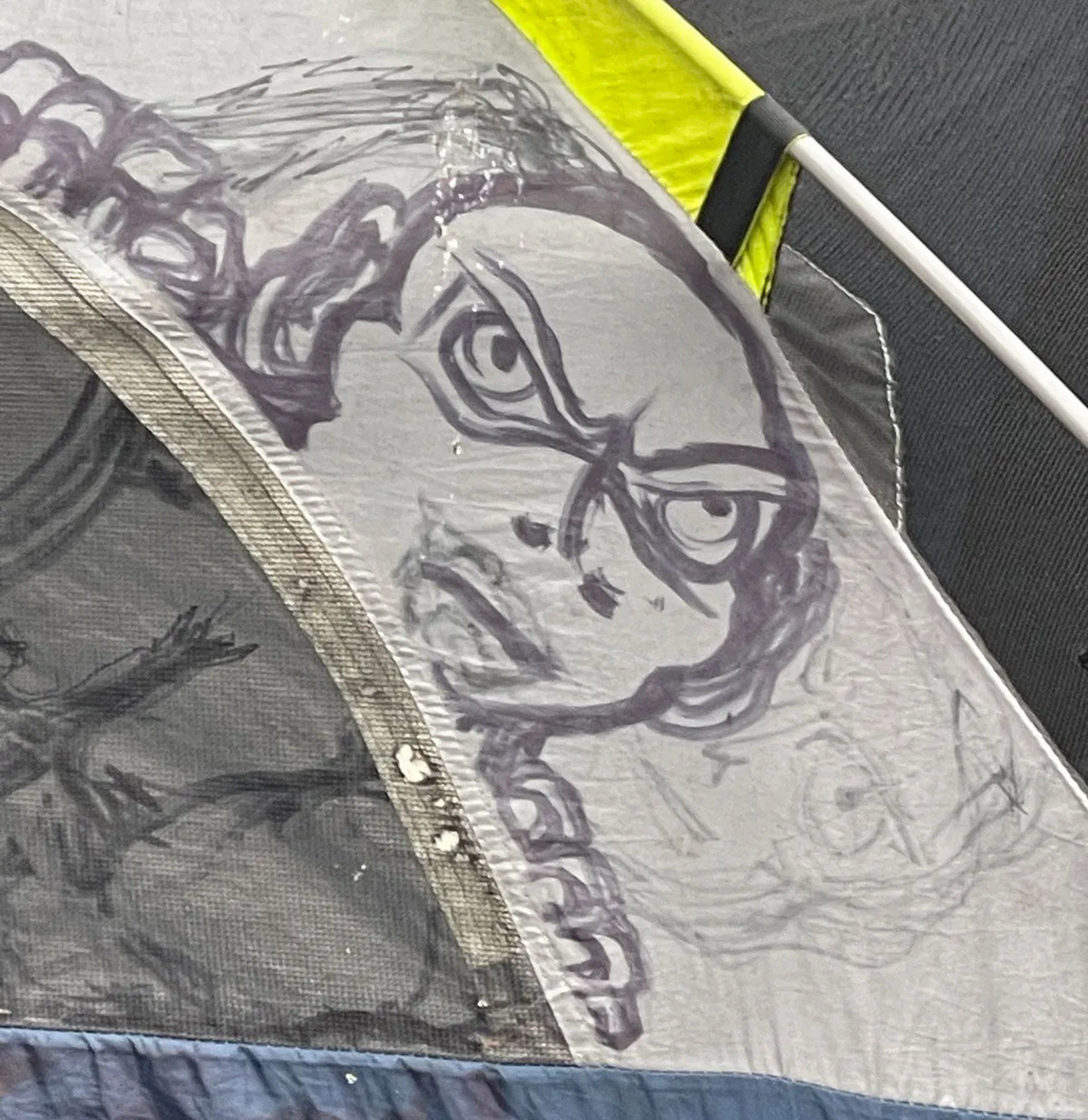

The largest of the tents is actually illustrated. Over a side window there is a face drawn in black Sharpie on the gray nylon material. The drawing is on the exterior of the tent, perhaps three-quarters of the size of a human face, but this face is closer to something from Marvel comics than one you might meet on the street. The illustrator has done that hard thing of putting fingers to either side of the face, making them so large that it seems as if the figure is hiding behind, holding on, and peering out over the screen window. It’s a haunting drawing, not great art but the eyes stare out at me for the entire time it takes for the hazmat men of DPW to throw the tent away.

The rules of engagement

The city conducts these operations twice a day, first at 7 in the morning and again at 1 in the afternoon. They follow a certain set order of operations.

First off, a cluster of city workers—members of the Homeless Outreach Team (opens in new tab) and the Encampment Resolution Team (HOT and ERT)—move from tent to tent, waking sleeping residents and telling them that the street needs to be cleaned and they’ll need to move their things. They are supposed to say—though whether they actually do is contested—that the resident will be allowed to come back after the cleaning is over. The city people also ask if the resident wants shelter or housing. If they do, the whole moving stuff business will be a lot simpler. They can just take what they need, and the city will get rid of the rest.

One problem with the protocol—and this is undisputed—is that at the beginning of the morning engagement, city workers do not know yet if or how many shelter beds are actually available. The city has closed the shelter system to self-referrals because it is essentially full. That doesn’t mean that no beds at all will be available on any given date, it is just that the beds that open will come from people leaving shelter, possibly for actual housing, but more likely because they are returning to the streets or to a hospital or are headed out of town. The city won’t be able to confirm that daily availability until later in the day, so the city workers tell the tent residents that they will circle back later in the morning with more information.

And it’s not just knowing if there is a bed in general. The city operates dozens of shelters, and they have different rules and capacities. Not all will work. If you have a dog, a shelter with a no-pet policy won’t do. If you are a couple, you aren’t going to split up for dormitory space. If you are in a wheelchair, you can’t climb stairs. And then there is the issue of your stuff. If you are only allowed to store a suitcase, you’d be giving up all of your possessions that did not fit.

An offer of shelter in the abstract is not meaningful; you need the details.

But meanwhile, the pack-up-and-move process goes ahead.

Tents that are unoccupied and not packed up may be determined to be abandoned. Abandoned tents and their contents—like the one I watched being dismembered—are loaded onto trucks bound for the dump.

Tents that are occupied but are not moved by the owner are supposed to be bagged up, tagged and moved to a city storage facility. The owner is supposed to be able to retrieve his or her possessions within the next 30 days; thereafter, they will be treated as trash and sent to the dump.

In litigation, the advocacy group Coalition on Homelessness (opens in new tab) is challenging the city’s compliance with protocols. It says that these operations are sweeps, which are currently banned under a federal injunction. The advocates say that police are often on-site during these operations to lend an air of coercive authority.

The cleaning, they say, is pretextual. Not the cleaning itself—the city does clean the street—but the motivation for doing it. The advocates argue that the cleaning is a way to harass and beat down the homeless, to create more pressure for them to get services, and to show the neighbors and the public that they are doing something.

What is happening, they contend, is not about cleaning the streets but about busting up the encampment, something a judge has enjoined.

Mobile homes

As I watched the 13th Street encampment being swept, I was struck by how much of the stuff around the structures is for mobility. If you don’t have a place to store things and are at risk of being forced to move at any time—some people have been swept dozens of times—you must be able to carry your stuff.

There are the little shopping carts that lived their former lives in high-end groceries, and for every one of them, there are two of the traditional big orange and red plastic carts that come from Target.

There are wheelchairs, baby strollers, joggers. Bicycles in every state of disassembly. There is a cart with three sides of metal bars and four wheels, like the dolly you might see in a department store for moving dummies around.

There are three small dogs in one of the tents. When they come out, they’re wearing little red colored coats for warmth.

As the morning progresses, a couple of tent dwellers are starting to pack up their tent. They move slowly, methodically. It’s a big process with all this stuff. Anything you don’t take is abandoned, and you aren’t renting a U-Haul. You have to roll it away yourself. You’d hate to have to do it once, much less frequently. Particularly without advance notice and in the rain.

There is one man—mid-50s, I’d say. Black. Wiry. Surprisingly cheerful. He takes two or three hours to put together his transportation. At the front, there is a working bicycle—it’s a beat-up beach cruiser in a light blue color—then there is a span from a silver outdoor aluminum ladder, not a step ladder, but a full get-up-on-the-roof-and-clean-the-drains sort of ladder.

The ladder has two homemade mounts so it can trail behind the bike parallel to the road, a long thin loading platform for everything else he is packing. The far end of the ladder is on a small dolly, the sort with four little hard black wheels that can each turn 360 degrees if they need to.

He has ropes and cords and bungies, no two the same, and as he adds things onto the bed of the ladder he lashes them down like he is preparing to take a ship to sea and could not have loose barrels skittering on the deck.

There is a black wheelchair on the street—not electric, but in pretty good shape, all things considered; it’s the sort of serviceable black wheelchair that might be queued on a jetway at the airport waiting for seniors to disembark.

The chair is waiting to be thrown over the side of the truck into the stuff heading for the dump, when the man with the bike and ladder sees it and heads over for a brief inspection. He likes what he sees and rolls the chair over to the dolly at the back of the contraption and attaches it there to roll along behind the long ladder.

With the wheelchair lashed on, he mounts the bicycle at the front and slowly begins to pedal.

The attachments move creakily along behind him. The rig reminds me of one of those long firetrucks that has a compartment in the rear with a second steering wheel, but he is doing this all alone.

There is no drama. No one is yelling at anyone. Everybody has done this before.

If the city’s purpose is truly to clean the street, I wonder why they are doing it while it is still raining. And why does it start at 7 a.m.? If you have the misfortune of living in a tent during the winter with the soaking rains, why is it required that you wake at 7 and move your tent in the rain?

I think of the street cleaners in my neighborhood. They don’t come at 7 a.m. I don’t know if they come in the rain but I doubt it. And if it is cleaning, why isn’t there a schedule? Every other Tuesday between 10 and 12?

The cleaning might be easier if there were large trash cans or dumpsters and scheduled pickups.

At first, I keep my distance from the residents; it feels impossibly rude—even for a reporter—to be approaching someone’s structure while their life’s possessions, their intimate objects, are in plain view on a wet city sidewalk. But no one seems to expect privacy.

They are used to this.

There is a woman across the street, her tent set apart from the others. Maybe she is 40, but I could be off by 10 years. People experiencing homelessness have told me that living on the street is particularly unsafe for women, and I wonder if her distance from the encampment reflects that fact, but I can’t bring myself to ask her about her safety when I see three stuffed animals in the things she is packing.

I talk to a young man named Justin Henninger, who says he is 28 and has been homeless since his father kicked him out of the house when he was 14.

He has been out of jail for a week and has been staying here under the overpass with his 3-year-old dog.

He notes that there has been a lot of rain this week and says, “My little tiny dog was soaking wet, and I’m pretty sure both of us got sick.”

I ask the dog’s name.

“Batman.”

I ask how he compares living on the street to being in jail.

“It’s really not far off. I mean, the only difference is I can go places. That’s really the only difference,” Henninger said. “Like in jail, you don’t get none of your personal belongings … out here, people are just going to take your stuff, so you don’t get that either. I can’t go work a job because I can’t leave my dog in a tent.”

He pauses and sums up the experience, “It sucks.”

This story was written by Joe Dworetzky of Bay City News.