Nearly 20 years have passed since a man named Protho Mathis allegedly failed to follow through with his court sentence for a crime he committed in San Francisco, and to this day court records indicate he is still on probation.

But Mathis, who would be 101 years old today, clearly is not reporting to his probation officer because he is dead.

An investigation by The Standard found that Mathis is one of an estimated 2,700 defunct cases that the Adult Probation Department has neglected to close, according to internal emails obtained through a public records request. The department is responsible for monitoring people and reintegrating them into society when they are released from prison.

A former research director for the department sent the estimate in a Feb. 6 email to agency Chief Cristel Tullock that explored the impact of closing 2,700 “old warrants” and cases of deceased people on the amount of state funding it receives. Those estimated 2,700 cases, which include people who the department hasn’t been in touch with for many years, would amount to over half of the department’s total caseload.

A chart in the email laid out three scenarios in which the department could correct its caseload numbers while still maintaining $3.06 million in annual state funding that’s intended to help San Francisco reduce its prison population without compromising public safety.

The department’s total caseload, which is currently listed at 4,969 people, is cited on the city’s annual performance score card (opens in new tab) and has appeared in budget proposals (opens in new tab). Mayor London Breed and the Board of Supervisors approved a roughly $58 million 2024 fiscal year budget for the department on Wednesday.

A System Error?

In an interview with The Standard, Tullock said she was unfamiliar with her former research director’s estimate, though the email indicates that the two met about the issue along with other top department officials in February.

Tullock acknowledged that the department doesn’t proactively check in on all of its clients, only interacting with many of them when flagged by other law enforcement agencies to do so.

She said that some people with suspended cases, meaning they have allegedly fallen out of compliance with their court sentence, may lose touch with their probation officers, and the department isn’t automatically notified when a client dies.

If a client is on suspended status for over a year, the department often stops interacting with them unless prompted to by other law enforcement agencies and closing out a case may require an extensive court process. As a result, someone who missed a court date 20 years ago could still appear in the department’s caseload.

“I can’t explain why that report was written,” Tullock said, referring to the estimate created by her former research director. “I’ve been in this seat for a year and a half. … I have really been working to get a handle on the landscape.”

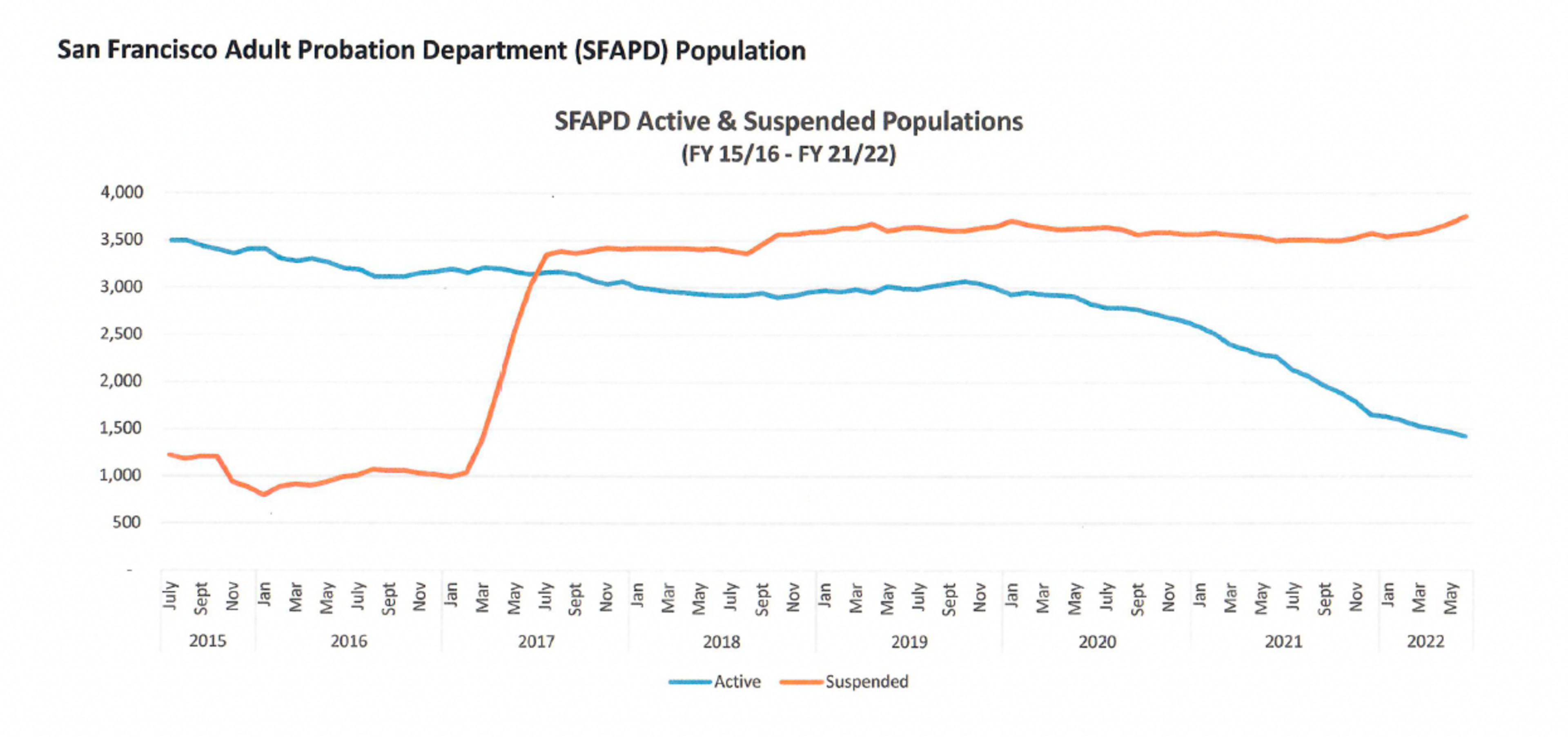

Though she denied having knowledge of the issue, Tullock said she believed that the defunct cases may be tied to a change in the department’s case management system around two decades ago. As a result of that change, and in an effort to come into compliance with federal law requiring the department to keep updated information on its clients, Tullock said the department discovered around 2,500 cases that it was previously unaware of in 2017. She said the department attempted to reconcile that error by retroactively adding those 2,500 clients to its caseload.

A line graph included in the Feb. 6 email to Tullock shows that the number of suspended probation cases skyrocketed over a five-month span in 2017 after it had decreased or remained stagnant the previous two years.

A Nationwide Issue?

David Muhammad, executive director of the National Institute of Criminal Justice Reform, told The Standard that the issue isn’t unique to San Francisco and he believes many other probation departments likely have defunct cases in their caseloads.

Muhammad contended that if a person has been on suspended status for over 10 years without being picked up by other law enforcement agencies, the probation department should just close out their case.

“If this person has been a saint for the last 10 years and has a warrant because they stopped checking in with their probation officer 10 years ago, that’s probably somebody we should just say, ‘Go and do well,’” Muhammad said.

Muhammed said that when he took over as deputy commissioner of New York City’s Adult Probation Department in 2010, he realized that around 20,000 of the city’s parolees were likely old warrants or dead people, and he enlisted a team of law school interns to assist in a multiyear effort to correct the inaccuracy.

“All of this is certainly not on the probation department and certainly not on the current leadership,” Muhammad said. “That being said, there should certainly be a plan to address it.”

Former San Francisco department Chief Karen Fletcher, who was head of the department at the time of the suspended caseload spike, couldn’t be reached for comment.

The San Francisco Superior Court appointed Tullock as chief in January 2022 and she has worked in the department for over 20 years. Tullock told The Standard that she would make correcting the department’s caseload a part of her strategic plan.

Using court records, The Standard independently verified four individuals who are still under the supervision of the department despite the fact that their cases are over 20 years old or they are dead, though there are likely many more such cases. Two of the probationers, Mathis and a person named Ivory Fuller, served in World War II and the Korean War respectively and are buried within 20 feet of each other at San Joaquin Valley National Cemetery.

Budget Decisions

In the past month, concerns over the department’s caseload arose in deliberations over its budget: The department’s budget has increased from $12 million in 2011 to a proposed $58 million in 2024, despite the number of people on active probation decreasing by 78%.

Tullock told The Standard that the department’s budget doesn’t necessarily correspond with the number of people it serves because the department has expanded rehabilitative services for its clients in recent years.

During a hearing on June 16, Supervisor Ahsha Safaí questioned Tullock about the number of people on suspended probation, asking for a breakdown of those clients by the level of attention that the department allocates to them.

Tullock told Safaí that the department’s suspended cases are divided into three categories: People whose probation is on pause as they await a court decision, those who have active warrants for their arrest and others who the department isn’t actively monitoring. Tullock described the latter group of clients who aren’t participating in the department’s services as “dormant.”

Tullock later provided a chart that states 63% of the department’s total cases are under limited supervision, which means the department doesn’t interact with them unless prompted to.

Safaí told The Standard he was unsatisfied with Tullock’s explanation. He contended that the department’s funding should reflect the decline in its client population in recent years.

“At the end of the day, all I want to know is how many people are on probation,” Safaí told The Standard. “If the list needs to be cleaned up, it should be a top priority for them.”

The Chief Probation Officers of California, an organization that represents probation departments across the state, didn’t respond to a request for an interview by the time this story was published.

Breed’s office didn’t directly address claims about illegitimate cases, but released a statement that said her office works with the department to ensure meaningful supervision of its clients.

Mathis, who died in 2005 of diabetes, lies in a grave around two hours away from San Francisco, still waiting for the city to close his case.