A San Francisco police officer is facing discipline after an investigation found that he repeatedly misreported the race of people he stopped, The Standard has learned. Police data shows he may not be the only officer inaccurately recording people’s races.

The officer allegedly misidentified the races of people he stopped in nearly half of the 50 encounters reviewed by the Department of Police Accountability, which investigates citizen complaints against officers. The investigation was spawned by a complaint alleging that the officer stopped and cited a person because of his race.

Like officers across California, San Francisco police officers are required to report to the state the perceived races of all people they stop, including drivers and pedestrians who are detained or searched. This mandatory data collection was put into place to address the long history of racial profiling by police in California.

The Department of Police Accountability found in early May that the officer under investigation mostly misidentified people of one particular racial group when he entered their demographic information into a state database, according to a summary of the investigation released by the agency. In some cases, the officer recorded the correct race of a person in police reports despite getting the race wrong in the database.

The investigation summary by the Department of Police Accountability did not name the officer or specify which race he regularly misidentified. However, it appears from San Francisco Police Department records reviewed by The Standard that the officer may be Christopher Kosta.

A June 2022 report by the Department of Police Accountability summarizing the complaints received by the agency includes a case number for the investigation. A public summary of the agency’s records requests to SFPD, in turn, repeatedly describes requests for information related to that case number as seeking data on stops by Kosta.

Kosta, 27, graduated from the police academy in 2019, department records show. He was transferred from Southern Station to an administrative position at the Crime Information Services Unit, otherwise known as the records room, by Police Chief Bill Scott on June 30, a police spokesperson said. Such transfers can be a sign that an officer is in trouble.

Kosta did not respond to requests for comment by phone and email, and SFPD declined to answer questions regarding a pending disciplinary matter.

These revelations come as a law enforcement scandal unfolds in Connecticut (opens in new tab), where an audit found that more than 100 Connecticut state troopers may have inflated the percentage of white drivers they pulled over while logging “ghost stops” that never happened. The U.S. Department of Justice is investigating.

Similarly, multiple law enforcement agencies in Louisiana systemically labeled Hispanic people they stopped as white, making it impossible to identify possible racial profiling, according to a ProPublica report (opens in new tab).

Law enforcement in Los Angeles has also faced scrutiny over inaccurate stop data. There, an audit found that sheriff’s deputies appeared to undercount more than 33,000 Hispanic people (opens in new tab) they stopped in a one-year period when entering data into the statewide system. Separately, when auditors reviewed video of 190 random Los Angeles Police Department stops, they found that officers entered inaccurate data in nearly 40% of incidents (opens in new tab).

In San Francisco, only one officer is accused of altering race data. However, an analysis by The Standard identified four other officers whose race reporting appears to stretch the limits of reality. One sergeant, for example, reported that all but six of the 1,139 people he stopped were white.

The allegations against the SFPD officer and analysis by The Standard raise questions about the accuracy of the stop data the department reports to state regulators. As is, that data shows that San Francisco police were five times more likely to stop Black people due to traffic violations than white people in recent years. That’s a similar rate to Los Angeles, though some of the Bay Area’s wealthiest enclaves have even worse disparities (opens in new tab).

Those long-running racial disparities led the San Francisco Police Commission to ban officers from making certain low-level stops as a means of preventing what’s known as a “pretextual stop,” or when an officer pulls over a driver on a hunch that the person committed a crime. The policy is still being discussed in labor negotiations and has not gone into effect.

Brian Cox, an attorney focused on police oversight at the Public Defender’s Office, said his office is calling for an audit of SFPD stop data by the Department of Police Accountability in response to the investigation.

“The open question is, how far and how wide is this practice in SFPD?” Cox said. “It’s fair to question whether that officer is in a league with others and if this is a common practice. If it is, it undermines all the work that the department has put in under the Collaborative Reform Initiative (opens in new tab).”

Sgt. Kathryn Winters, a San Francisco police spokesperson, could not come up with a reason why officers would want to falsify race data. She said officers who do so intentionally could face consequences including discipline, termination and even decertification under a new state law (opens in new tab).

“There is no incentive to misreport races,” Winters said. “In fact, there are many disincentives.”

Ken Barone, associate director of the Institute for Municipal and Regional Policy at the University of Connecticut, said tracking the racial demographics of police stops is meant to shore up trust in law enforcement.

“All of these examples only lead to further erode that trust,” said Barone, who advised on the design of the stop data collection system in California and was speaking in the broader context of the Connecticut scandal.

Melanie Ochoa, who sits on the state board that collects and analyzes the stop data of every California law enforcement agency, said the data is used to guide state policy and, in some cases, used by defendants in criminal cases to argue that their stops are racially motivated.

“Having accurate data is crucial,” said Ochoa, who is also the director of police practices for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California.

The Department of Police Accountability found that the actions of the officer in the San Francisco case “undermined the integrity” of the local stop data.

‘A Big Red Flag’

The Standard reviewed a roughly three-year period of SFPD’s stop data ending in 2021 and discovered that other San Francisco police officers have logged racial stop data that strongly diverges from the demographics of the city.

The sergeant who recorded improbable race data reported stopping just two Black people, four Asian people and zero Latino people out of 1,139 stops in the time frame. That sergeant reported that 1,134 of the people he stopped were white. (He marked that one person was both Black and white.) Most of those stops took place in the Richmond police district, where about 37% of residents are Asian.

“That should be raising a big red flag for police administrators if they’re routinely looking at their officers’ data, which they should be,” said Barone, the stop data expert.

When asked to what extent SFPD reviews the stop data officers report for inconsistencies in the reporting of races or indications of racial bias, Winters, the department spokesperson, said the department has a plan to implement a management dashboard to analyze stop data.

Barone, who trains officers on implicit bias, said that there can be a fear among some officers that if they stop too many people of color it could somehow count against them.

“So there may be motivation to make the drivers you’re interacting with appear whiter than they are because of that sort of fear of how the data could be used against you,” Barone said.

During the same three-year period ending in 2021, three officers consistently reported that people they stopped belonged to five, six or seven racial groups. For example, these officers may have recorded an entry that said that a single person they stopped was Asian, Black, Hispanic/Latino, Middle Eastern or South Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander and white—all at the same time.

One officer did this in about 70% of 144 stops. The other two officers stopped 98 people and marked five or more racial groups in 87% and 76% of their stops, respectively.

The law requiring police to collect racial data instructs officers to include all races that the person appears to be. But it does not provide guidance on what to do if an officer doesn’t know which race to select, Winters said. The data collection system does not provide officers with an “unknown” or “other” race option to check.

Officers are not supposed to ask the person they stopped what their race is for the purposes of entering that information into the state database. They are only supposed to input the races they perceive.

Ochoa said officers who mark five or more racial groups for individuals may be filling out their data entries incorrectly. Inaccurate data entries have plagued every California law enforcement agency that Ochoa has reviewed, she said. The omissions, she said, have been more likely to obscure police interactions with Black and Latino people than other racial groups.

“Even though this data seems to be skewed downwards for Black and Latino people because of inaccurate reporting by the officers, we still see disproportionate stops and actions taken towards Black and Latino individuals across the state,” Ochoa said. “So even with the missing data, it still demonstrates how significant that disparity actually is.”

Whether an officer intended to alter the race data of people they stopped or entered the wrong races because they were too lazy to capture accurate demographic information, Ochoa said the problem is serious.

“In either case, the officer needs to be identified and disciplined for not following the law,” Ochoa said.

Fudging the Numbers?

The misconduct case against the officer, whom records indicate is Kosta, began when a man filed a complaint with the Department of Police Accountability in June 2022. The complaint accused the officer of stopping and citing him because of his race, according to the summary of the investigation.

The man had been smoking cannabis and was in a parked vehicle with his friend when the officer stopped them and cited him for driving without a seatbelt. The officer searched both of them as well as the vehicle.

When investigators looked into the complaint, they found that the officer improperly identified the race of the man and his friend in the state stop data system. This led to a review of the prior 50 stops by the officer.

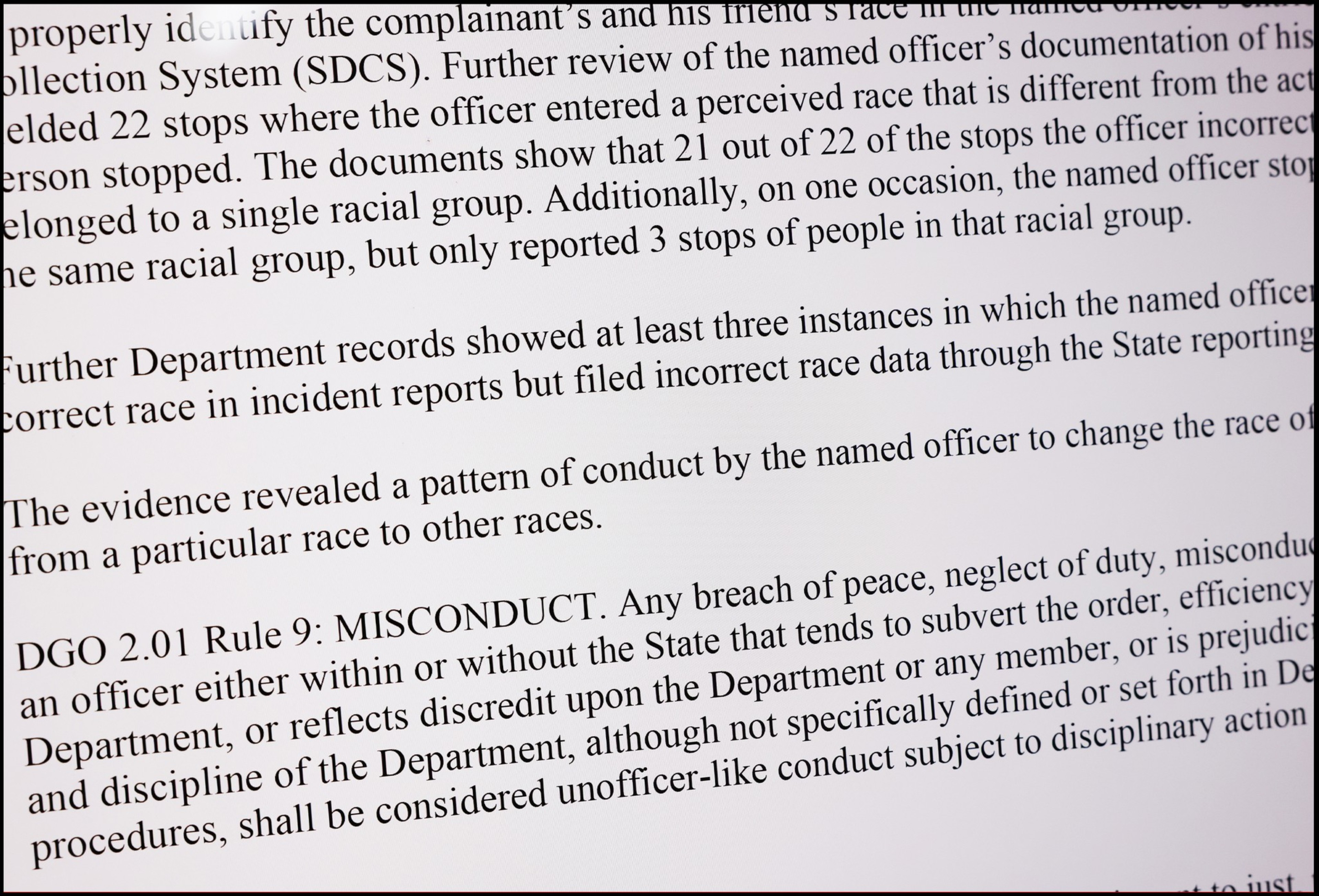

The investigators found 22 stops in the state data system where the officer entered a perceived race that was different from the “actual race” of the person stopped, the Department of Police Accountability investigative summary said. Twenty-one of those 22 incorrectly logged stops were of people who belonged to one particular racial group. In at least three instances, the officer got the race of a person right in his incident report while reporting the race wrong in state stop data.

The officer denied stopping the man because of his race and said that he was not trying to change the data, according to the summary. The officer stated that he does not perceive race or use race to inform his law enforcement decisions and that he input the data at the end of his shifts to the best of his recollection of events.

But the Department of Police Accountability found that the officer committed misconduct by knowingly engaging in biased policing or discrimination. Among the agency’s other findings were that the officer did not have cause to search the man or cite him for driving without a seat belt.

While the Department of Police Accountability reaches conclusions about whether an officer committed misconduct, it cannot unilaterally punish officers and can only recommend that the police chief or Police Commission impose discipline.

Police Commission records from July indicate that the officer is facing disciplinary charges in front of the body, though the disciplinary process is opaque and it’s unclear where the case stands today.

Officers whose cases are heard by the Police Commission can face serious consequences, including termination.