The kids apparently went to bed, because Garry Tan is back to war. It’s nearly midnight, and he’s been firing off tweets with the precision of a sawed-off shotgun. Hot takes and ragetweets may be the coin of the realm in Elon Musk’s new world order, but even by social media standards, Tan’s metabolism for vitriol and the breadth of his disdain for what ails San Francisco is staggering.

Over the course of two hours, the CEO of startup incubator Y Combinator personally attacks or retweets criticism of “extremist judges,” whom he accuses of emboldening criminals with the help of local media; any supervisor who dares to oppose bonuses to hire more cops; Nancy Pelosi and lawmakers concerned about the safety of autonomous vehicles; education activists who want to change math curriculum in public schools; venture capitalists who are “evil” to startup founders; “decels” who want to pump the brakes on technological progress; Apple’s monopoly on apps; YouTube censors; and last, but certainly not least, NIMBYs.

This behavior would be less remarkable if Tan, 42, weren’t a centimillionaire and one of the most influential people in tech. He boasts 362,000 followers on X (formerly Twitter) and a quarter-million subscribers to his YouTube channel. He has also poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into local elections since 2021.

Tan’s critics have attempted to brand him as a toxic tech bro who lacks empathy and political chops, but he’s more than a malcontent with a big microphone. In just a few years, Tan, a registered Democrat, has fashioned himself into San Francisco’s preeminent political pitbull, an attack dog with a taste for progressives.

“One thing that I’m starting to realize about myself is I always look for chaos,” Tan said in an interview this month at Y Combinator’s cavernous headquarters, a former power station in the city’s Dogpatch neighborhood. “Most people want certainty. They want to feel comfortable. And then the true founders, they want to find chaos, and they want to turn chaos into order.”

Five things we learned from our bare-all interview with Sam Altman

Tan, who lives with his wife and two young sons in Noe Valley, also wants San Franciscans to join him in picking up their pitchforks come election time in November 2024. The city is on pace to smash its own record for drug overdose deaths, more than 4,000 people are sleeping on the streets every night, and property crime and quality-of-life issues have made San Francisco a national punchline. With businesses fleeing and vacant Downtown towers collecting dust, the city could be creeping toward a fiscal crisis.

Regardless of whether people like or loathe Tan, both his supporters and detractors acknowledge that few people—perhaps only Mayor London Breed—have greater influence at this moment over the city’s political discourse.

“Where does this guy have his pull? It isn’t in banking votes in San Francisco politics. It’s in that broader, end-around messaging: the negative light that has been cast on the city,” said David Latterman, a longtime political analyst in San Francisco. “Locally, people might just roll their eyes. But you can’t deny that the national spotlight through these means—and it’s a negative spotlight—has been enough to get Breed to react. And so, in effect, it does work.”

In turn, online attacks against Tan are becoming increasingly aggressive, which may be why his list of accounts he’s blocked on X numbers in the tens of thousands.

A website called Techbro SF (opens in new tab) has been trolling Tan and his political allies, circulating an image that shows Tan’s visage on a squid, suggesting his tentacles control political groups and the media—including, incorrectly, this publication. The graphic harkens back to a racist “Mongolian Octopus” (opens in new tab) illustration circulated in the late 1800s to bolster arguments against Asian immigration. Tan’s attacks on progressive supervisors who are Jewish, such as Dean Preston and Hillary Ronen, have led to accusations of antisemitism. One progressive commenter called Tan a “lil Nazi snake.” (opens in new tab) Tan responded by calling the posts smears and saying he is “a big fan of Jewish people.” (opens in new tab)

The political maneuverings of wealthy power brokers in San Francisco have always been met with deep suspicion and pushback. Tan saw firsthand how progressives blamed people like his mentor Ron Conway, a billionaire venture capitalist, and the tech industry at large for driving up the cost of rent and gentrifying neighborhoods (opens in new tab). Conway receded from the spotlight after dramatically shaping city politics during Mayor Ed Lee’s administration (opens in new tab), but it appears there will be no such backing down with Tan.

“Every way they come after me,” he said, “I’m going to go after them 10x.”

‘Prototypical, Testosterone, Poisoned Tech Bro’

Tan’s massive social media following—and real-world clout as leader of what some consider the top startup incubator in the world—gives every acerbic tweet about housing, the drug crisis and public safety a special weight among the city’s tech and political classes. Over the summer, he and Musk started replying to each other’s posts (opens in new tab), giving Tan an even larger reach thanks to the budding digital bromance.

In direct broadsides on X, Tan has drop-kicked state Assemblymember Matt Haney for “virtue signaling” (opens in new tab) on the drug crisis, tagged Supervisors Connie Chan and Aaron Peskin as part of the “corrupt political machine,” (opens in new tab) suggested Ronen has the IQ of a borderline intellectually disabled person (opens in new tab) and declared all-out war on Preston (opens in new tab), a Democratic Socialist. Tan has also called for abolishing citizen oversight groups like the Police Commission, a proposal political insiders have scoffed at as an example of naivete.

Peskin said he has never met Tan but sees him as a “prototypical, testosterone, poisoned tech bro.” The supervisor questioned Tan’s goals beyond “throwing bombs.”

“He definitely donates money to campaigns,” Peskin said. “But he doesn’t seem to be a [political] player that is actually looking for solutions or sitting down and trying to have mature conversations about how to make the city a better place.”

Tan has contributed more than $278,000 to political campaigns since early 2021, putting him in the top tier of individual spenders in San Francisco. While Tan has made it abundantly clear whom he doesn’t support, he’s more evasive about whom he plans to back in next year’s elections.

This summer, Tan held a fundraiser for Breed at a condo he owns near Dolores Park in the Mission. Breed’s approval ratings have plummeted since the start of the pandemic, and the private event offered the beleaguered mayor a chance to rekindle support from her frustrated base.

Tan, who supported Breed’s appointments of District Attorney Brooke Jenkins and Supervisor Matt Dorsey, considers the mayor to be a “friend” and said the two text each other. But even after giving money to her campaign last year and throwing her a fundraiser, he won’t commit to officially backing Breed in the November 2024 election.

“No,” Tan said. “I’m a big fan, and honestly, we don’t even know who the field [of candidates] is yet. So, it’d be way premature to say either way. I can say I’m a fan and supporter. Like, she’s definitely going to be on my ranked-choice vote.”

A day prior to his interview with The Standard, Tan met Daniel Lurie, an anti-poverty nonprofit founder and heir to the Levi Strauss fortune who is running for mayor. Tan said he walked away from their conversation impressed.

Tan’s support is likely to carry enormous sway in the city’s growing collection of moderate-leaning political groups, some of which Tan is advising. Tan sits on the board of GrowSF, a moderate group launched by two former tech workers, and is part of the “donor table” for Abundant SF, a coalition of upper-crust tech entrepreneurs who plan to pool millions of dollars to spend on city elections each year starting in 2024.

Tan’s chaotic foray into politics appears to mark a new era from the high-society, ball gown and bowtie power brokers of the past.

“The old guard of people in politics, kind of like the Downtown developers and the Shorensteins (opens in new tab) and the Fishers (opens in new tab), that’s a different class,” said Todd David, political director of Abundant SF. “When I think of the new generation of business leaders, especially the young ones, it’s hard for me to think of anyone who is more important than Garry.”

‘People Just Read It and Engage’

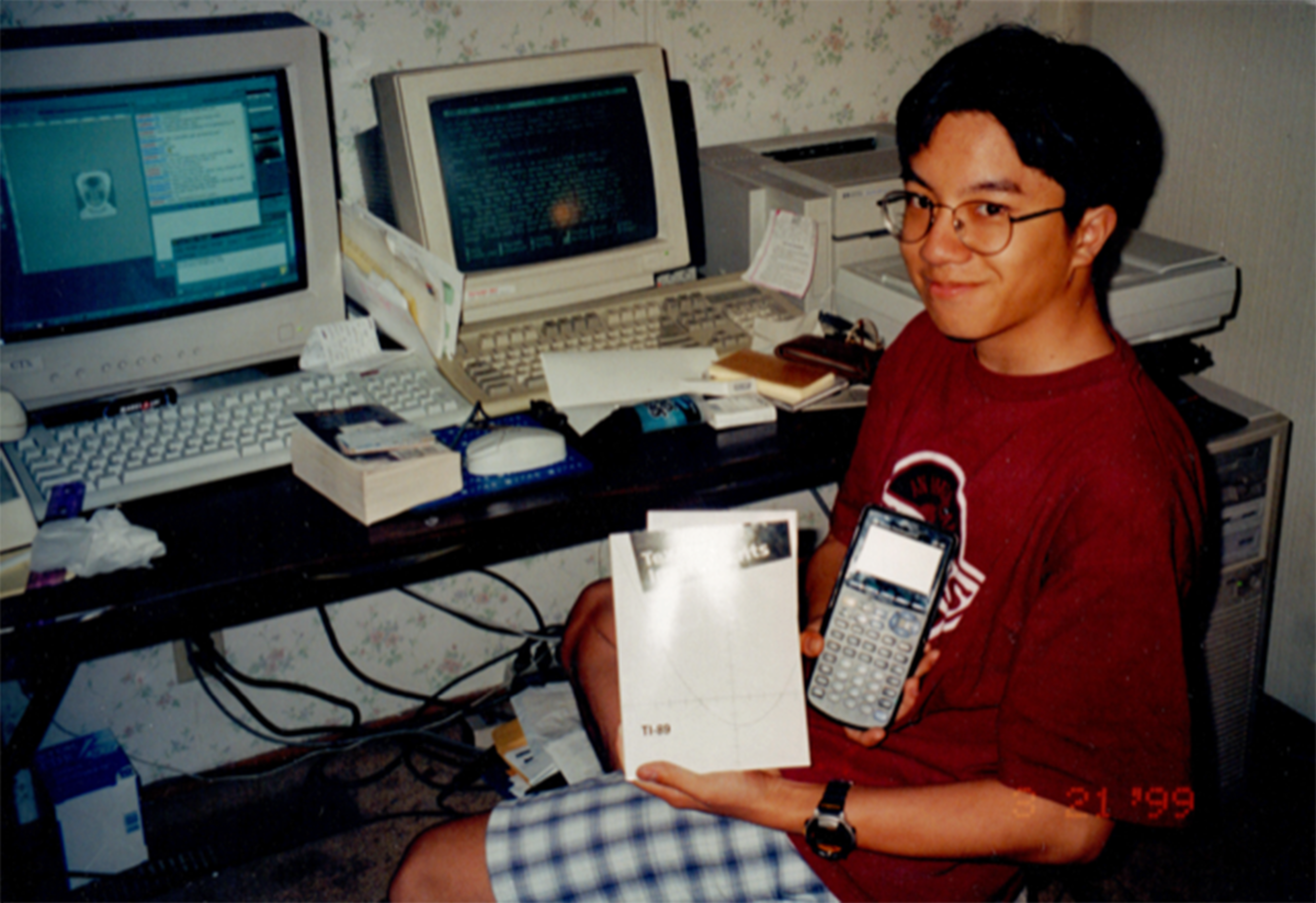

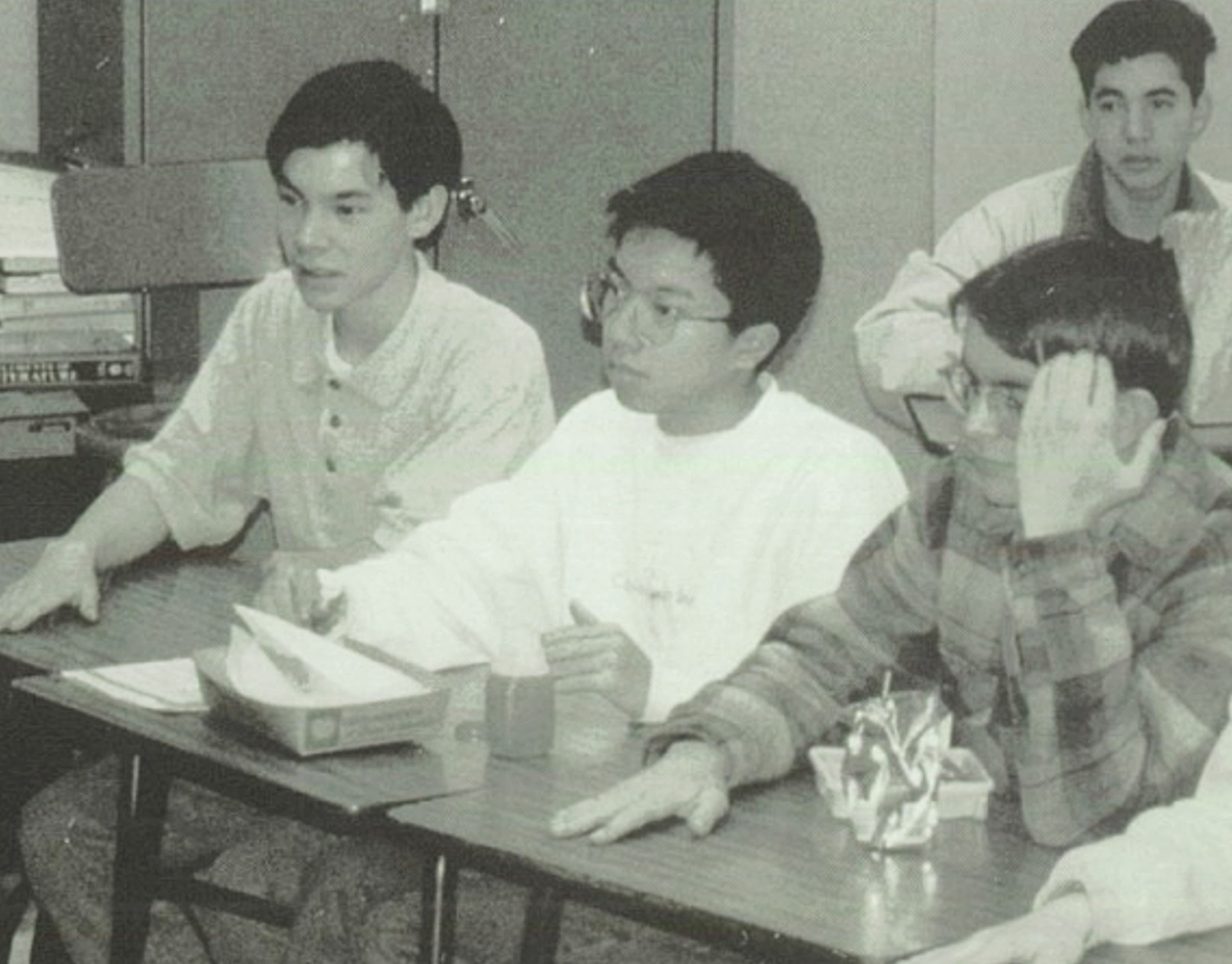

Tan’s origin story is far from glamorous, and the trauma he endured as a child, along with the training he received, seems to have made him uniquely suited for the stress of startup culture and San Francisco politics. He was born in 1981 in Winnipeg, Canada. His ethnically Chinese parents—his father was from Singapore and his mother was from Burma—met at an A&W Root Beer restaurant and struggled to make ends meet.

The family moved around—once to California, then back to Canada—before settling in Fremont in 1991. His dad, a mechanical engineer, drank too much and changed jobs often. His mother’s limited English skills prevented her from trading in her two jobs, including work at a convalescent home, to pursue her dream of becoming a registered nurse.

Tan’s father would come home and pass off machinist paperwork to Garry, the eldest of two sons, so he could relax and drink beer. Food was often in short supply—in interviews, Tan has recalled meals of sliced bread dipped in milk (opens in new tab)—and his father’s discipline could be severe. The tension of home life was paired with mundane family outings in which his father would take him to technical bookstores, preparing Tan for a life of building and breaking things.

“It’s hyper common for founders to basically have limbic systems that are tuned up in a way where if it’s, like, too calm or too safe, they start looking for things to find stimulation,” Tan said.

At age 14, Tan started cold-calling companies in the Yellow Pages to land a $7-an-hour job building city websites, a grind that eventually paid off with Tan helping his parents make a down payment on a house. In middle school, Tan and a friend created a website that became an “underground newspaper” tackling thorny issues like California’s three-strikes law.

“I just got addicted to this idea that media was a way that you could actually have an influence on the world around us,” Tan said. “And on the internet, it sort of didn’t matter who you were. People just read it and engage with it.”

Obviously, the difference now is what Tan says matters.

After graduating from American High School in Fremont and receiving a computer engineering degree from Stanford in 2003, Tan worked at Microsoft and became an early employee at Peter Thiel’s Palantir. He joined the Y Combinator program as a partner in 2011, and a year later, he sold his first startup, a blogging and sharing platform called Posterous, for $20 million. He created another company similar to his first before launching Initialized Capital, a venture capital firm that hit big with Instacart and Coinbase.

Tan has voted in all but one San Francisco election since 2014 after moving to the city about two years earlier. Tan contributed $5,139 to various campaigns in 2015 and 2016 and supported Sonja Trauss and other YIMBY housing activists. But it wasn’t until the 2022 district attorney and school board recalls that Tan—infuriated by the city’s public school system and a spike in hate crimes targeting Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI)—began more aggressively speaking out and pouring money into campaigns.

“You see this in Garry and, just in general, in how the AAPI community is voting right now,” said Lee Edwards, a friend of Tan’s and a fellow venture capitalist. “When you look at safety and you look at public schools, these are things that the community cares a lot about, particularly if they’re first-, second- or third-generation immigrants.”

Kim-Mai Cutler, a close friend of Tan’s who worked as a tech journalist before joining his former investment firm, Initialized Capital, suggested the departure of Donald Trump from the White House has made San Franciscans like Tan less concerned with assaults on democracy, LGBTQ+ rights and immigrants; instead, they are taking a harder look at the conditions here at home.

“That [wave of electing progressives] was very much fueled by the Trump presidency and people wanting to make a clear statement that they were as far away from that as possible,” Cutler said. “In some ways, maybe Garry’s trajectory mirrors that shift in the tone of city politics.”

‘The More I Find Out About Him, the More Angry I Get’

It isn’t difficult to see how Tan and Supervisor Dean Preston see the world in different colors.

In contrast to Tan’s hardscrabble beginnings, the 53-year-old Preston grew up in Greenwich Village with the safety net of generational wealth before coming to San Francisco to work as a tenants rights attorney. Eight years after Tan and his family arrived in Fremont, Preston and his wife were buying a 2,400-square-foot home overlooking the Painted Ladies and Alamo Square.

“We’re, like, exactly the polar opposite,” Tan said. “I don’t think I’ve found a single thing I agree with him on. … What’s funny is I don’t think it’s personal. It was the policies that made me angry first. And the more I find out about him, the more angry I get.”

GrowSF launched a campaign committee this summer colloquially called the “Dump Dean PAC,” with Tan contributing $50,000 to the effort. The group’s website ticks off 31 reasons why voters should not reelect Preston, whose supervisorial district includes the Haight and the Tenderloin. The arguments against Preston range from his opposition to numerous housing projects and calls to defund police to his stances against last year’s recall elections. Tan has recited many of these points in dozens of social media posts, accusing Preston of “ruining” (opens in new tab) San Francisco.

The contempt appears to be mutual.

In an appearance this month at the First Unitarian Universalist Society of San Francisco, Preston—who joined the Board of Supervisors in 2019—blamed the city’s ills on wealthy elites and a “billionaire backlash” that he said has rolled back progressive reforms.

“Even worse than the billionaires like Musk are the wannabe billionaires. Like, they only have hundreds of millions,” Preston said. “Guys like Garry Tan and others, they’re very angry that they’re not yet billionaires, so they’re even more toxic.”

Tan laughed when he heard about Preston’s speech being posted to YouTube, which also features a channel Tan has fine-tuned with advice from social media star Mr. Beast (opens in new tab) to share life lessons and business strategies.

“Like, they’re anti-capitalists,” Tan said. “I’m a capitalist! Basically, I feel like I have to [fight back]. It feels like a little bit of a duty.”

The war between Preston and Tan is clearly personal. But a recent exchange shows how Tan’s social media tactics can act as a double-edged sword. The same day Musk pledged to double Tan’s $50,000 donation to GrowSF, Preston sent out a call for donations saying that he is running against the “billionaire class.”

Bilal Mahmood, a tech entrepreneur who is expected to challenge Preston in next year’s election, attempted to distance himself from Musk in a post on X. While he has little in common with Preston, Mahmood’s reaction could have just as easily come from one of the supervisor’s supporters—a seeming acknowledgment that, in Preston’s progressive district, any association with the divisive billionaire would be a political non-starter.

“San Francisco is a city of progressive values,” Mahmood tweeted. “Elon should keep his fucking money out of our politics.”

‘What Happens in San Francisco …’

Last summer, Tan was lured back to Y Combinator as CEO to carry the baton previously held by tech whisperer and Y Combinator co-founder Paul Graham as well as Sam Altman, who is now the CEO of OpenAI.

Tan has been bullish in defending the work of Y Combinator founders and calling out “greedy” investors. But unlike his predecessors, he’s also more politically outspoken and believes an alignment between San Francisco tech founders and policymakers could spark a global movement for the betterment of humanity.

“I never want to run for office. Like, it’s not for me to figure out,” Tan said. “I really think that we can find people who have our values, who believe in the acceleration of human abundance. And those are the people I want in power. If we align ideologically, this is the city to do it. And what happens in San Francisco will not just be for the people who grow up in San Francisco. It’ll be for the Bay Area. It’ll be for California. It’ll be for America. It’ll be for the world.”

The handle of Tan’s X bio includes the acronym “e/acc,” which stands for effective accelerationism. The ideology du jour in Silicon Valley—endorsed by venture capitalist Marc Andreessen and convicted pharma bro Martin Shkreli—suggests rapidly scaled innovation and capitalism can create social change bordering on a utopia. There will be collateral damage, the theory goes, but this should not be seen as a reason to “kill the golden goose,” as Tan put it in a defiant YouTube video defending robotaxis in San Francisco.

The ideology has fringes that border on cultish—such as those who believe in a “thermodynamic god” (opens in new tab)—but Tan sees e/acc as a motivating force in bringing more tech people into San Francisco’s political fold.

“We’re trying to get tech people to realize: ‘You may not be interested in government, but government is absolutely interested in you,’” he said. “And you know what? I’m not asking for more than a vote. I just want our vote. That’s it.”

Tan’s influence in this regard appears to be bearing fruit. In just the last two weeks, Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff has come out hard on public safety after largely sitting on the sidelines since 2018 when he backed Proposition C. The controversial ballot measure taxed companies making over $50 million in annual gross receipts to help fund homelessness services, but conditions on San Francisco’s streets are no better, and critics say the tax played a role in driving businesses out of the city.

“I think he’s coming over,” Tan said of Benioff. “I think that he understands the unintended consequence [of Prop. C]. And he’s pro-police, he’s pro-public safety and I’m excited about that.”

There is a question as to how long Tan can keep up the pace of raising a family, serving as CEO of Y Combinator and acting as San Francisco’s chief political antagonist. Blocking tens of thousands of people on X can silence some of the noise—and conversely, create a dangerous echo chamber of thought—but one meltdown or poorly worded tweet can lead to becoming persona non grata in this city.

“Folks burn out or wear out their welcome pretty quickly,” Latterman said. “[Tan] takes one issue that’s really unpopular—you know, some kid gets killed by an automated vehicle—and then suddenly he’s out defending it? Then his cred is done.”

Some of Tan’s supporters and friends have expressed concern about the toll of his social media brawls: “I can’t see that level of Twitter fighting is great for anyone’s psyche long-term,” Cutler said. But Tan said he rarely suffers a moment of doubt in his mission.

“Not really,” he said. “I mean, yes, but I care about this, and it’s worth it. Like, what other game of FarmVille (opens in new tab) am I supposed to be playing?”

Tan used to play video games on his family computer as a kid, trading floppy disks with his friends. When asked what he does for fun now outside of picking political fights, he smiled, almost confused by the question.

“Oh, my God,” Tan said. “This is fun.”