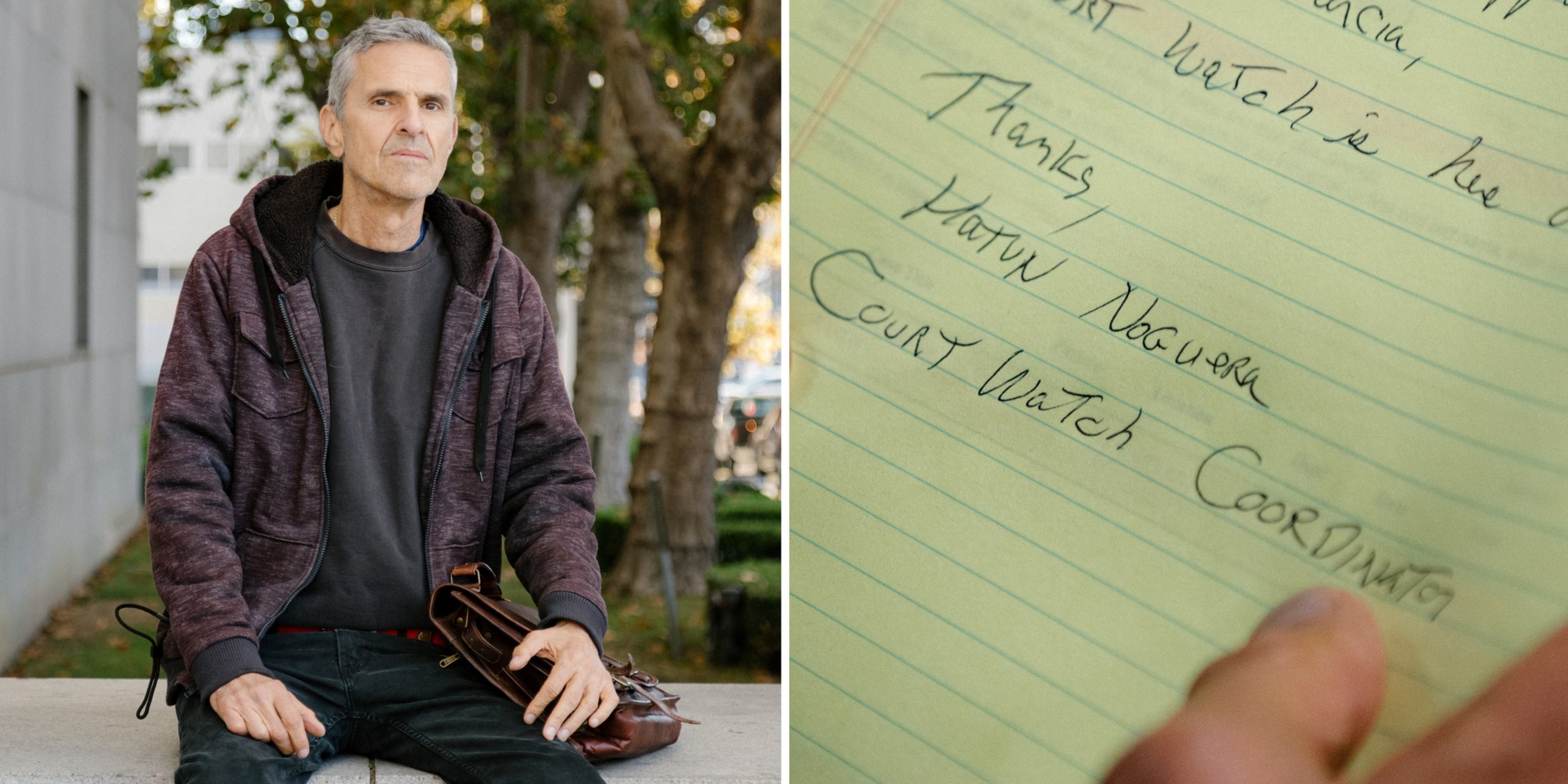

Judge Eric Fleming had a direct view of him. Hatun Noguera, a tall, thin man in his 70s with short-cropped gray hair, sat in a courtroom at San Francisco Superior Court in the second row behind the prosecutor.

On that November morning, Noguera was monitoring several cases. A pile of legal pads sat on his lap with the defendants’ names written on multicolored sticky notes. The night before, he’d printed out the case details from the court’s website and the county jail’s website.

Noguera is not a police officer or a court employee. He’s there to observe the judges.

When a prosecutor passed by, Noguera handed him a yellow piece of paper. “Court Watch is here to observe. If the opportunity to notify the judge of our presence in the courtroom occurs, please let him know that we are here,” Noguera’s note said. But the prosecutor was busy and quickly exited the court without saying anything to Fleming.

For nearly two years, Noguera has spent most weekdays calling court clerks to check up on about 50 cases he follows. He comes to court for important hearings. And he’s not alone.

Noguera is a member of Stop Crime SF, a neighborhood crime watch organization-turned-nonprofit that is pushing for harsher treatment of repeat criminals and more transparency around legal outcomes.

Stop Crime SF has roughly 5,000 members and financial links to a billionaire who bankrolled much of the recall of then-District Attorney Chesa Boudin in 2022. The group has been vocal about linking “lenient” judges to crime, focusing on their track records on pretrial release, and that message has been echoed by District Attorney Brooke Jenkins, the San Francisco Police Officers Association and others. The group’s focus on judges comes as violent crime rates in San Francisco remain lower than comparably sized cities, but rates of some property crimes remain high.

“I was feeling unsafe and then found the organization,” said Noguera, who has an alarm system, video cameras and a two-by-four that bars his door at his home west of Twin Peaks.

The group described (opens in new tab) a sentence for time-served handed down in a Union Square looting case in this way: “This dangerous serial offender is out of custody entirely with a get-out-of-jail card issued by Judge (Linda) Colfax.”

In its short history, Stop Crime SF has taken on Boudin’s administration in a legal battle over records, pushed for legislation that aimed to reduce theft from rental cars and advocated against at least one San Francisco judge—Colfax—for appointment to a state court. It’s also taken aim at the Police Commission, which it blames for creating policies like limits on when officers can initiate car chases that hamper police from doing their jobs—even if that policy predates the current commission.

But by its own assessment, the group’s most important task—and the one for which it has gotten the most recent attention—is its court watch program. It plans to grade 14 Superior Court judges who are up for election in March.

“That is the most important thing our organization is doing,” said Stop Crime SF board member Karina Velasquez, an immigration lawyer. “Our public safety depends on the legal system, and we need a system that works.” The group says it doesn’t oppose giving people in the legal system second chances but says far too often, repeat offenders are cycling in and out of the system without any real consequences.

The yet-to-be-released report card is under preparation as two judges face opponents backed by Stop Crime SF’s sister organization, Stop Crime Action.

San Francisco Superior Court Judge Michael Begert is facing a challenge from Albert “Chip” Zecher, a corporate lawyer and board member of UC Law San Francisco. Judge Patrick Thompson is facing a challenge (opens in new tab) from Deputy District Attorney Jean Myungjin Roland.

Critics say Stop Crime SF is not just a nonprofit trying to educate the public about judges and criminal justice, but rather a politically motivated group whose court watch program is part of a larger effort that is undermining trust in judges. Jurists, these critics note, must make rulings based on the law but are bound by a code of ethics (opens in new tab) that bars them from publicly commenting on their rulings or any controversy that may come before them. Judges also point out that allegations of opacity are false, given that every decision made in court is open to the public.

“We encourage the public to educate themselves about the judiciary. There’s nothing wrong with that,” San Francisco Bar Association Board President Vidhya Prabhakaran said. “But the suggestion that judges are somehow (opens in new tab) intentionally fomenting criminals and crime in the city of San Francisco is ridiculous.”

Supervisor Aaron Peskin was less circumspect about Stop Crime SF, which he said was part of a “right-wing assault” on the judiciary.

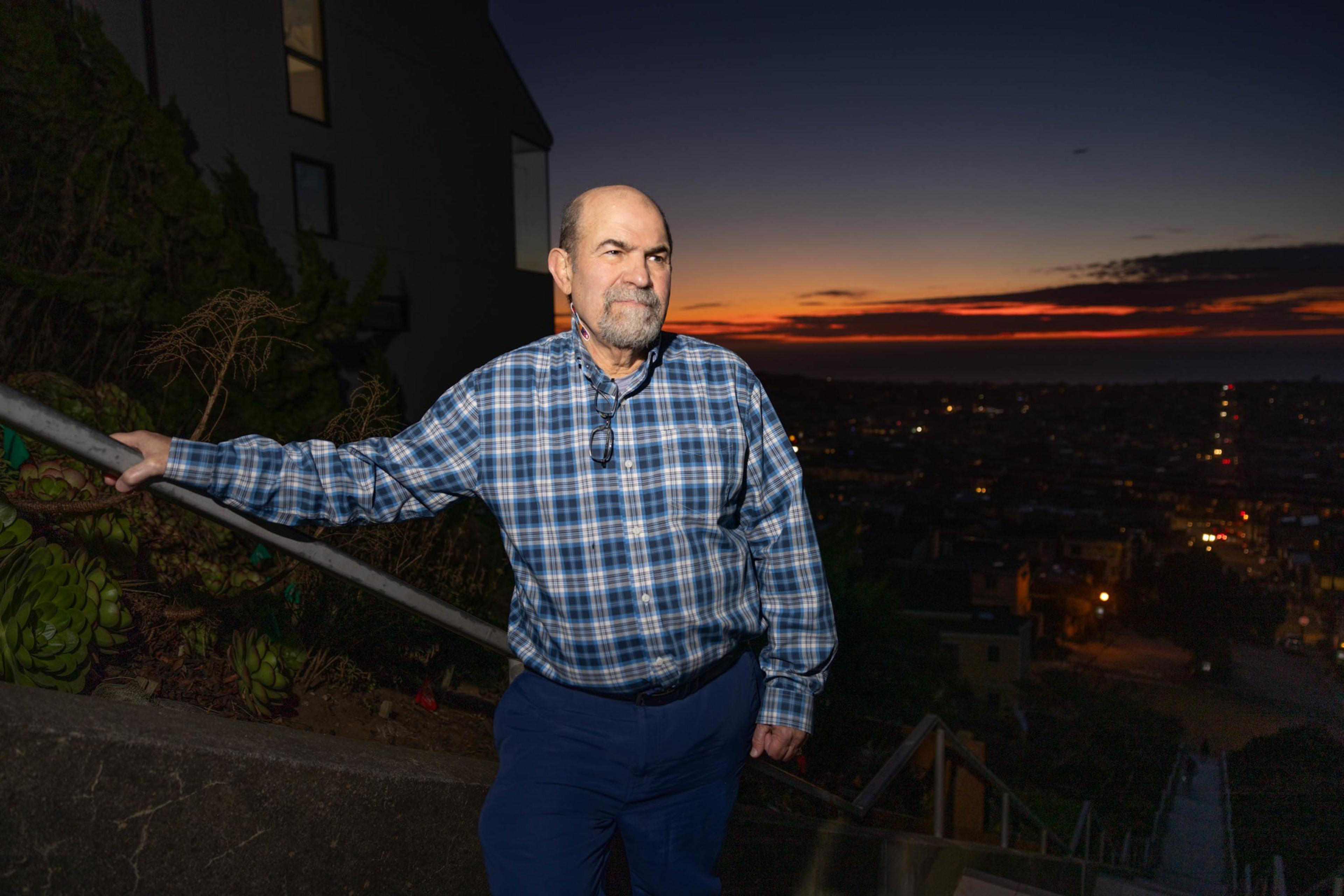

Frank Noto, Stop Crime SF’s head, bristled at such characterizations, saying he has been a Democrat his whole life. Peskin’s attacks, he said, amount to interfering with the public’s right to vote for the judges they want in office.

How Tiled Stairs Led to the Birth of Stop Crime SF

The tile staircase at 16th Avenue and Moraga Street has drawn tourists and Instagram users alike to its bright swirling designs since it opened in 2005.

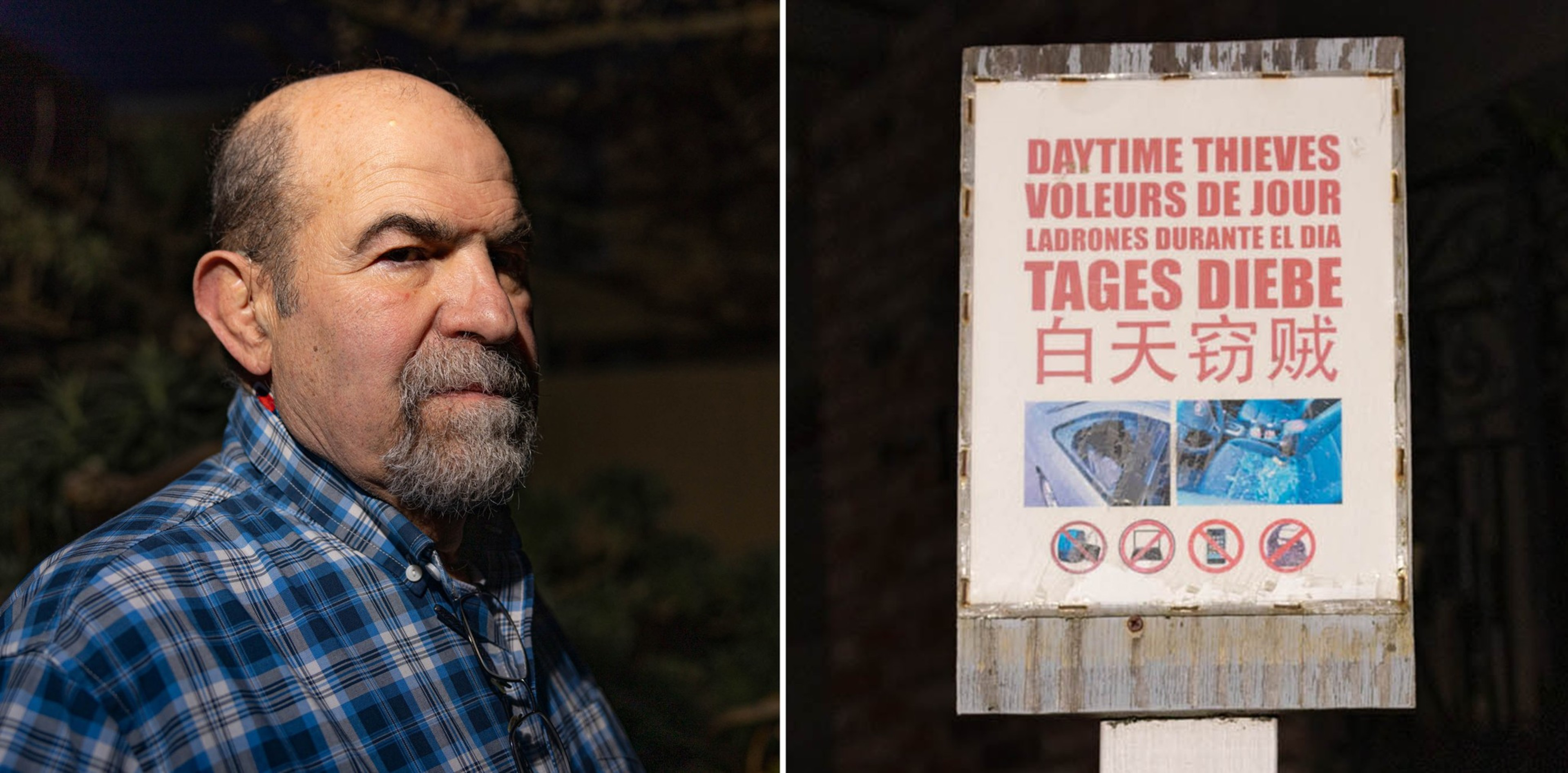

But as soon as the stairs were unveiled, thieves were drawn to those tourists, said Noto, who, in addition to being president of Stop Crime SF, also leads Stop Crime Action, its sister 501(c)4 nonprofit. “After they built it, the tourists were followed by burglars,” he said.

Noto and a group of about 20 neighbors met in a garage in 2017 and started sharing their experiences with crime. That meeting was the beginning of Stop Crime SF.

Noto’s professional experience was suited to the task. He spent much of his professional life as a lobbyist and PR man for developers, fighting local efforts to stop their projects. His firm, GCA Strategies was founded by a now-deceased land-use and NIMBY expert, Debra Stein (opens in new tab). Noto, who remains its principal, said he is a 1% owner. The firm’s managing partner, Milo Trauss—whose sister, Sonja Trauss, founded the YIMBY Party—is currently working for a landowner who wants to develop mostly market-rate housing at 2588 Mission St (opens in new tab).

Stop Crime SF’s first move was to go to the neighbors’ then-supervisor, Norman Yee, for legislation forcing rental car companies to obscure decals and insignia indicating a car is a rental; Stop Crime SF believed doing so would make them less visible targets for thieves.

The group, not yet legally a nonprofit, continued to advocate for legislation, more police resources and educating voters on its vision of the criminal justice system. In 2018, it held district attorney candidate debates and, in 2020, judicial debates.

Over this period, the court watch program was born, focusing on repeat offenders, judges who released them and property crime.

In 2017, car break-ins in San Francisco peaked at 31,000. They have yet to reach such heights since.

“We would go to car break-in trials just to show the judge that other people cared,” Noto said.

Joel Engardio, who would go on to be elected as a San Francisco supervisor, served as the executive director of Stop Crime SF from 2017 to 2022. He used skills developed from his unsuccessful 2016 campaign for supervisor to build a website and expand the group’s outreach and public image.

In 2020, the group went from being a loose volunteer group to a 501(c)3 nonprofit with a mission to “serve as an advocate for victims, work with police and prosecutors and advocate for the resources they need.”

By 2021, Boudin was district attorney, and the Covid epidemic had transformed the city. Stop Crime SF took aim at what it said was Boudin’s lack of transparency around cases, such as detention, convictions and sentencing.

“We tried to get information about drug violations, for example,” Noto said of drug dealing and possession cases. “But we couldn’t get that, so we filed a [Public Records Act request], and they stalled.”

It took thousands in legal fees for an attorney, but the group got the documents and put them online where anyone could research the outcome of any criminal case.

An employee of the District Attorney’s Office at the time said Boudin’s staff was taking steps to make that data public anyway, and Stop Crime SF only used it to instill fear in the public.

“They were never really interested in the truth,” said Dylan Yep, who was a data analyst under Boudin. “They were just interested in pushing their agenda. Their agenda was to make people afraid … so that they could push right-wing carceral racist policies. And it worked.”

Yep contends Stop Crime SF cherry-picks cases, highlighting those in which someone was released and then reoffended. But such stories are not necessarily representative, Yep said.

Engardio pushed back, saying Stop Crime SF’s requests for case outcomes were politically agnostic. “Information and data is good no matter what side of the political spectrum you are on,” he said.

A turning point for the group and its court watch program came when photographer Edward French died in a robbery gone wrong on Twin Peaks.

“It was kind of traumatizing for our volunteers,” Engardio said. Many of their volunteers were elderly, like French, and saw how property crime can turn violent.

The trial of French’s alleged killers dragged on, said Noto, with defense attorneys using every tactic in the book to lengthen the process. At one point, Boudin fired the prosecutor. Then, the case ended with a hung jury. A retrial is pending.

“So, they delay, and they delay, and our judicial system allows that. It’s really criminal,” Noto said, adding that the group expanded its focus from property crimes to more serious crimes after French’s death.

The case of Troy McAlister (opens in new tab), who killed two women when he drove into them in a stolen car on New Year’s Eve in 2020, is another example the group points to as a sign of the system’s dysfunction. McAlister had a long criminal history and had been arrested days before, on Dec. 20, for allegedly driving a stolen car, but was released.

Such cases have led the organization to establish its judge report card. Early this year, the group created a committee that will make the final judgments based on a variety of sources. The committee, which has four or five members, will review case outcomes and judicial rulings collected by court watch, as well as appeals and a survey sent out to all judges, defense attorneys and prosecutors.

Prosecutors are the only group that participated in significant numbers, Noto said. The judges responded as a body and said they could not comment.

The group has yet to decide whether the grading will be numbered or lettered A to F.

“The group is called Stop Crime SF. It shouldn’t surprise anybody that Stop Crime is concerned with the judges and the criminal courts,” said John Trasviña, the former dean of the University of San Francisco School of Law, who is one of the committee members in charge of Stop Crime SF’s judge report card.

His role on the committee grew out of being the victim of a stickup. The man who robbed him had been released to care for his grandmother during Covid in a separate Marin County case; he was eventually convicted.

“Some people would say, ‘Look at this judge who would let this guy out,’” he said.

San Francisco judges do not comment on their rulings, but Presiding Judge Anne-Christine Massullo did write a statement in response to the report card.

“Judges take an oath of office to apply the laws of California impartially and fairly to the facts presented in a case,” she said. “When a law changes, as it did with the [California] Supreme Court decision of In re Kenneth Humphrey, judges must apply the new law.”

Humphrey governs when and how people can be detained. Detention without bail requires prosecutors to convince a judge that there is an imminent danger to the public and that no alternative to detention exists.

Financed by a Billionaire

The first year Stop Crime SF filed taxes, in 2021, it reported raising $131,134 in revenue.

Its largest donor was Neighbors for a Better San Francisco, a group founded and headed by Bay Area billionaire William Oberndorf, who gave the organization $100,000, according to tax filings. The organization (opens in new tab) was also a main funder of the Boudin recall. The billionaire has give the majority of his funding dollars—with a few Democratic exceptions—to Republican candidates and causes (opens in new tab), including support for Senate Minority Leader Mitch O’Connell.

Because of rules governing 501(c)3 nonprofits, Stop Crime SF is not allowed to back anyone in a political campaign for office. But the group is allowed to lobby for (or against) policies and appointments.

Noto’s 501(c)4, Stop Crime Action, which also received funds from another Oberndorf charity, can and does endorse politicians. Contributions to 501(c)4 groups are not tax deductible. Stop Crime Action received $650,000 from the Oberndorf charity Neighbors for a Better San Francisco Advocacy in 2021, according to tax filings.

Noto acknowledged that both groups’ largest donor has been Oberndorf but said that funding was mostly in 2021 and had no link to the current effort to grade judges. Neither group has filed its 2022 taxes, Noto said.

Funding aside, Noto acknowledges the organizations are closely linked.

“Some of the same people are members of both organizations, and we share information,” he said. “Obviously, the relationship between Action and SF are much closer because I’m on the board of both of them.”

Regardless of the legal wall between the groups, their messaging often overlaps. On Nov. 9, Stop Crime Action emailed its followers, blasting Begert and Thompson, the two judges in the contested races.

“Judge Begert and Thompson are by far the worst judges on the Superior Court and have a demonstrated track record of releasing serious and dangerous offenders back into the public,” Noto wrote on behalf of Stop Crime Action. Stop Crime SF’s Twitter account later retweeted Stop Crime Action’s statement.

Begert (opens in new tab) runs the Community Justice Center, a diversion-focused part of the courts, and Thompson oversees a court that handles preliminary hearings. Both were among the judges targeted by anonymous posters alleging they had let drug dealers walk pending trial.

Thompson disagrees with Noto’s characterizations. For one, Thompson said, he has worked in the traffic court for much of his time on the bench. Since January, he has worked in preliminary hearings, which do not often deal with the release or detention of defendants. Preliminary hearings are for the judge to rule if there is enough evidence to go to trial.

Thompson said Stop Crime Action’s targeting of him is part of a cynical effort to manipulate public frustration about crime and lawlessness.

“They are tapping into that energy, and I am being identified as someone in leadership who should change,” Thompson said. “But my role is to play it by the book.”

Begert said in a statement that he has both held people accountable and helped turn people’s lives around while following the letter of the law.

On the same day that Noto sent his email to followers, a crowd rallied on the steps of City Hall to voice its concern about efforts to blame judges for crime and lawlessness.

First District Court of Appeal Justice Teri Jackson’s speech encapsulated the general sentiment, which was that judges are supposed to apply the law, not bend their actions to political pressure.

“We are not here to get tough on crime. We’re not here to be liberal on crime,” she said. “We are here to apply the law so that everyone who comes in our courts has a fair trial.”

Editor’s Note: This post has been updated to more accurately reflect William Oberndorf’s history of political giving and to clarify that Noto did not know Oberndorf was linked to funding Stop Crime Action and Stop Crime SF.