In February, a person wearing a hood walked into Expert Pet, a pet store in San Francisco’s Ingleside neighborhood, and went straight into the employee bathroom. The staff heard a destructive racket—banging and shattering tile—for several minutes and called the police. No officer ever arrived, and after several minutes, the vandal left.

The owner, Mike Sorrels, who was away at his store’s Dogpatch location at the time, repaired the smashed tile and refastened the sink and toilet. When he read in May that crime in San Francisco was down in every category, he didn’t believe it. “There’s no way, with the lack of police presence and the lack of officers actually on the street, that crime has come down,” Sorrels said.

That’s a common sentiment among the city’s merchant leaders, who say minor crimes are still a major problem for their businesses. And they have a sympathetic ear among some police leaders who don’t believe the department’s statistics tell the full story of what’s happening with street crime. Now, those police leaders are enlisting help from businesses to show what they suspect is really going on.

At a meeting of the Chief’s Small Business Advisory Forum in March, Assistant Chief David Lazar expressed concern that crime was going unreported and suggested that merchants develop an app to log reports. (Lazar, who declined to be interviewed, said through a spokesperson that he is “willing to talk with the community about any new ideas to use technology to better assist the SFPD.”)

Al Casciato, a retired police officer who’s been involved in conversations about the app, said the data would be useful for staffing the department and deploying officers. He likened the effort to Yolo County’s “FastPass to Prosecution” program (opens in new tab), which allows participating big-box retailers to send nonemergency crime reports directly to the district attorney’s office and sidestep the friction that disincentivizes reporting.

“You can type in ‘My window was broken,’” Casciato said. “You take a couple of pictures and send it in. You get your window fixed and you’re not waiting two days for the police department to show up to take a picture and to make a report.”

Randall Scott, head of the Fisherman’s Wharf Community Benefit District and a consortium of the city’s benefit districts, is leading the app’s development. The app, he said, will be advertised to small business owners through the dozens of merchant associations and community benefit districts across the city and allow users to make simple reports with pictures for nonemergency crimes.

“Everyone’s reporting crime is down,” Scott said. “Well, those are the metrics—and without anything else to point to, you gotta go with what it says. This could be something else to point to.”

But would fresh data of that sort clarify the picture or muddy it? Certainly, it would add fodder to the already high-pitched debate around retail theft, smash-and-grabs, and other threats to public safety and order. That debate looks to be central in this fall’s mayoral race, with the four top candidates leading their campaign websites with their commitments to public safety (Mark Farrell and Daniel Lurie), police staffing (Mayor London Breed) and citywide community policing (Supervisor Aaron Peskin).

To a significant degree, Breed is staking her reelection hopes on the premise that crime is rapidly receding after a few years of pandemic-induced spikiness. Any successful challenge to that narrative would be a potential blow to her campaign and to other efforts by the city to shed its public perception of lawlessness (opens in new tab).

A spokesperson for Breed’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Dark figure of crime

Crimes go unreported for a variety of reasons. The victim may not realize a crime occurred; the bad actor may be known to the victim; the victim may harbor a fear of retaliation or mistrust of the authorities. In criminology, the phrase “dark figure of crime” is sometimes used to evoke the difficulty of measuring the portion of crime committed but never officially logged.

For 50 years, the Bureau of Justice Statistics has conducted an annual study called the National Crime Victimization Survey (opens in new tab), in which a nationally representative sample of people 12 or older is interviewed to produce a better picture of incident rates. In 2022, the most recent data available, the United States experienced 13.4 million property victimizations. The rate of reported and unreported property crimes, ranging from burglary to theft, was 101.9 victimizations per 1,000 households, which was markedly higher than the 2021 rate of 90.3 per 1,000.

Outwardly, SFPD is optimistic about the decline in crime this year, attributing the decline “to our hard-working officers and new department strategies to address specific crimes,” a spokesperson said. “[W]e have not seen any evidence to indicate that fewer crimes are being reported now versus any time in the past.”

Involving police in minor crimes—a cafe’s stolen tip jar or graffiti on an apartment building—can require victims an amount of time disproportionate to the value of stolen items or property repairs.

“Almost everyone I know has had some petty crime happen to them that they didn’t report, even car break-ins,” Police Chief Bill Scott said in an interview after a recent community meeting. “I’ve seen shootings that don’t get reported until someone shows up at the hospital with an infection.”

When it comes to unreported crime, he said the department doesn’t know what it doesn’t know and relies on the public to report. He said the department’s online reporting system has been improved, but he does think an app would encourage people to report more.

Frank Noto, a leader in the Stop Crime SF advocacy group, believes the city is leaving behind a period in which crime went unreported.

“People felt, particularly during the pandemic, that it didn’t matter if they reported minor crimes,” Noto said. “I suspect that that attitude is beginning to change because they see that police are more energized. The number of people who go to jail is up. The system is beginning to work.

“Getting more people to report it is a way of improving the quality of life in San Francisco and reducing crime ultimately, so that’ll be a good thing,” he added.

Too many apps

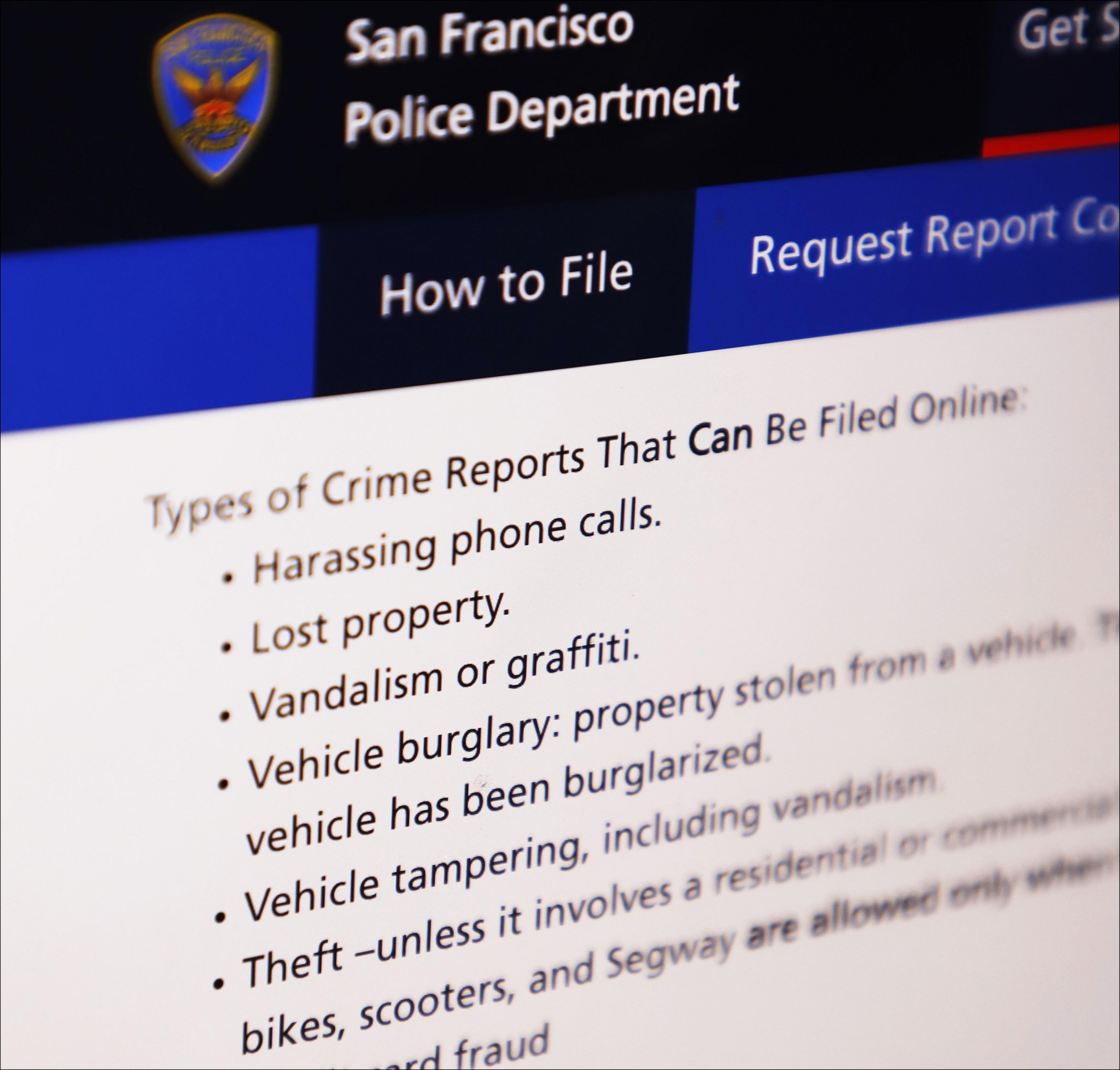

For nearly 20 years, San Francisco has used LexisNexis Coplogic (opens in new tab) to let the public formally report minor crimes online, in person, or by calling 311.

Approximately 2,000 police reports are filed monthly for various minor crimes ranging from burglary to theft and vandalism, LexisNexis spokesperson Annalysce Baker said. Nearly half of those reports are completed via mobile device each month.

But the SF311 app and site, which handle 75% of the 50,000 or more calls each month, doesn’t integrate with Coplogic. People can complain about illegal dumping or commend a Muni driver’s performance, but they can’t fill out or even be redirected to the police reporting form.

For the forthcoming crime app, the group is working with Jia (opens in new tab), a company that provides a platform used by the city’s business and community benefit district workers to track incidents—picking up trash or painting graffiti—and close 311 tickets for the city. The standalone platform may be named Report Here SF and could go live toward the end of the year.

Henry Karnilowicz, the Chief’s Small Business Advisory Forum’s founding co-chair and a South of Market Business Association member, said reporting crime online to the police department or through 311 has been confusing. The new app is “for small business more than anybody else. We’re the ones who get impacted most I think, rather than just your regular residents,” he said.

But Karnilowicz is of two minds on the new app. “Not many people know about Coplogic, but everybody knows 311,” Karnilowicz said. “It should be integrated into 311; we shouldn’t create another app—I’ve got so many goddamn apps on my phone.”

Christin Evans, a merchant leader in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, said empowering small business owners to create data is a good thing. For instance, her business association tracks retail theft and commercial vacancies. And despite dystopian depictions in the media, she said there’s been significant quality of life improvements. The neighborhood directly benefited from voter-approved funds for housing and caring for formerly homeless people.

“To continue the recovery in the post-pandemic period, we need to ensure that people have an accurate picture of what’s going on in our streets,” Evans said. “It’s really important to be honest about our real safety challenges, but I also think it’s important not to overblow those challenges. And it’s important to recognize that a lot of work has been done to ensure safety.”