“Are you going to go after the bad guys?” asked Mark Philpot, a Bayview resident who works as a nurse in the Tenderloin.

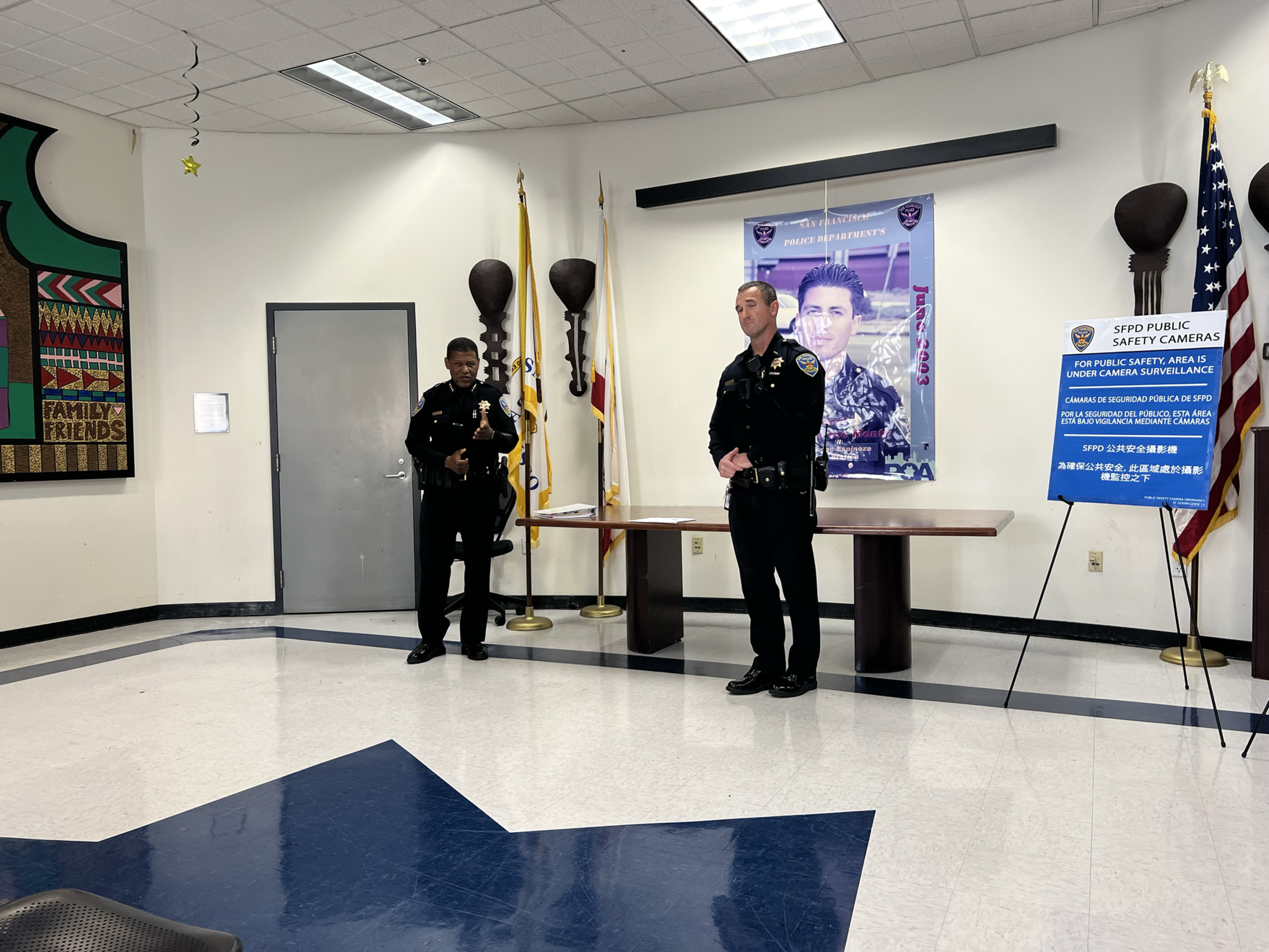

Philpot was one of a dozen Quesada Avenue residents whose frustrations erupted at an Aug. 20 town hall at the San Francisco Police Department’s Bayview Station. A meeting that was supposed to be about public-safety cameras turned into a forum for Bayview residents who’d had enough of the shootings, confrontations, and fear caused by the drug trade returning to their block.

Chief Bill Scott stepped to the front of the room and raised his hands, trying to bring the topic back to how a network of cameras (opens in new tab) would reduce crime.

“We’ve used the cameras pretty effectively for drug dealing, and we know that there is drug dealing out there,” the 34-year law enforcement veteran said. “We have the ability to record footage. If someone is complaining and we do an operation, we can see what’s going on and we can get the right people.”

The residents were ready to tell the longtime police leader about the open drug dealing in their neighborhood and weren’t going to let him get away without providing answers — especially in light of resources to combat the drug trade being concentrated in the Tenderloin, when they need them too.

‘A forgotten area’

Lifelong Bayview resident Linda Pettus has lived on Quesada Avenue since 1970. The 72-year-old remembers the upheaval in the ’60s over police brutality and has watched as the neighborhood missed out on the prosperity that buoyed the rest of the city.

“I don’t know what can be done,” she said, standing outside her home. “Bayview-Hunters Point has been a forgotten area for — as far as the city is concerned — years. We’ve heard the same thing from different police captains and supervisors. It’s really the same things that we’ve been hearing over the years: There’s always not enough police. My biggest thing now: Why focus so much on the Tenderloin and not other areas of the city?”

Down the block from Pettus’ front door, men hang out in a van parked beside a partially renovated community center. The sliding door is open, and drivers pull up alongside the van or park in front of the median to do business. Sometimes, six to eight vehicles are double-parked at once.

More than 50 people a day double-park in a right-turn lane or in front of the median, blocking the narrow street, sometimes for hours, to buy drugs from dealers working the corner. Residents have been yelled at and threatened; their cars get shot up. Philpot had to ask nicely that a man stop urinating on his garden. When they complain, 311 directs residents to take photos of offenders’ vehicles — a risk many aren’t willing to take. (At the meeting, Scott said he does not encourage people to put themselves at risk.)

But meaningful solutions have been elusive. There have been 72 police reports at the intersection over the last year, for incidents ranging from carrying weapons to disorderly conduct. While police have run operations on the corner — a drug arrest was made in July — the problems crop back up.

A retiree who cares for her mother, Pettus was once stuck inside her house when a shooting turned the sidewalk into a crime scene.

One neighbor, Keith S., was unimpressed by the camera proposal.

“I almost couldn’t get out of the street because they were double-parked getting their drugs,” he said. “Police cars drive down Third. How come they can’t stop and say, ‘WTF are you doing? Move.’”

Much of the frustration stems from the fact that while law enforcement and city agencies get involved, nothing seems to change.

In the past, Quesada Avenue neighbors worked with police and the district attorney, even going to court to obtain stay-away orders against drug dealers. The double-parkers returned.

Residents use 311 to get parking control officers and police to issue more tickets. If nothing else, maybe it would drive the trade to move elsewhere. But ticketing double-parked vehicles is usually a nonstarter; the drivers can leave before an officer arrives or a citation is issued.

Besides, said an SF Municipal Transportation Agency spokesperson, it’s beyond the scope of the job: “Attempting to use parking control officers to dissuade criminal activity, without the presence of law enforcement, can also expose them to safety hazards that they are not trained or equipped for.”

At a minimum, residents want the SFPD to park a squad car — manned with an officer or without — on the street as a deterrent.

Bayview Station Capt. Mike Koniaris told the residents at the meeting that he would place a vehicle on the street and assign the community violence reduction team to the location. But, he told The Standard later, his options are limited. The station is understaffed: no plainclothes team and few beat officers. The station needs 158 officers to operate at recommended levels, but in July staffing was down to 78 (opens in new tab).

The mayor’s office said it’s aware of the situation.

“While shutting down open-air drug markets remains a major priority in the Tenderloin and SoMa neighborhoods, Mayor Breed will continue to allocate resources and respond to calls for services citywide and adapt our response to changing crime trends,” a spokesperson said. “Just within the last month, SFPD officers arrested a person for suspected illicit drug activity in the area around Quesada Avenue and Third Street, and their van was towed.”

At the Aug. 20 meeting, residents said they were particularly irked by the fact that the narcotics unit is focused exclusively on the Tenderloin and South of Market neighborhoods.

Scott countered that the SFPD has officers who can make drug arrests. “Even though the narcotics [unit] has been in the Tenderloin for pretty much the past year, we can still make narcotics arrests, and we do in other parts of the city, and a lot of that happens at the station level until we increase the size of our narcotics unit.”

‘A dangerous corner’

Ashley Bostwick has had enough. The Quesada Avenue resident’s car has been hit by gunfire twice. She often finds herself parking blocks away so she doesn’t have to confront double-parkers. She has been complaining to the police and 311 for two years.

So Scott’s attempt to talk up cameras didn’t inspire her. “The meeting was discouraging, because if there have been cameras there the whole time, why doesn’t anything change?” Bostwick said.

The cameras, Scott contends, don’t stop the crime but can help with investigations.

“Because we’ve been using cameras on some of our narcotics investigations, the cases have been really good,” he said. “If people are getting convicted, it’s because the evidence is there. I think it’ll make us better at what we do and help get some of these problems to a better place.”

Historically home to the city’s largest Black community, Bayview-Hunters Point is now made up of about 40% Asian American residents, 27% Black, 22% Latino, and 9% white. Median household income is $80,000, making it one of the lowest-income areas of the city. It’s a place defined by working people, not by the extreme poverty of the Tenderloin, and so, the residents feel, it doesn’t demand enough of the police’s attention.

“We just don’t have the resources to be at all these places at one time,” Scott said, and the worst places are the priority. The good news, he said, is that the SFPD budget from the Board of Supervisors will allow for new police hires. Still, he admitted, making arrests is one thing; changing behavior is another.

“Who are the people that are out there?” he asked. “That’s a rhetorical question — because I know who they are. They’re people, mainly, that live in the community. They are people that have been doing this for years, and we need to change the code and some of this, but we have to do it the right way.”

Scott reminded the Bayview residents that the dealers are neighbors, too. “If people live in the community, they’re not just going to disappear,” he said. “We just have to change the culture where these things aren’t permitted to happen, and that usually happens over time. [It’s] not going to be overnight, but we have to do our job.”

Philpot and other neighbors said they get the sense their corner is being treated like a crime-containment zone.

“I get the feeling that they’re not that invested, or that they like to have things localized, and they don’t mind that it’s on our street,” Philpot said. “We’ve been so frustrated, and it’s such a dangerous corner.”

Philpot and Pettus have witnessed the cycle. Once the dealers dig in, their customers know where to find them, traffic increases, and the possibility of violence grows. Once someone is hurt or killed, law enforcement will crack down. But only for so long.

At the end of the meeting, Scott was optimistic. “My prediction is we’ve been successful with making arrests and cleaning up problems, and I think that’ll happen in the Bayview with the use of these cameras,” Scott said. “It’s not going to solve all the problems.”

Then he asked whether the participants wanted the cameras. There was a resounding yes.