Running as the lone progressive Democratic candidate in one of the nation’s most progressive cities arguably should make you a shoo-in for any office.

But Supervisor Aaron Peskin has had an easier time swimming the briny bay from Alcatraz to shore (opens in new tab) than he has building a winning coalition for San Francisco mayor.

Peskin hasn’t consistently cracked the top two vote-getters in polls this entire election season. Only now, as moderate Democrat candidates barrage each other in a siege of attack ads (opens in new tab), has Peskin nudged toward the top three choices in recent polls.

So what are the chains holding Peskin down?

Is he being buried in an avalanche of billionaire money? They’re trying (opens in new tab). Has his years-old, salacious reputation for bullying hung like an albatross around his neck? His high negative rating (opens in new tab) in polls shows there’s some truth to that. Or is it just plain tough for an older white guy to light up progressives when Vice President Kamala Harris, a multiracial woman of color, is top of the ticket? OK, maybe that too.

Still, all of those challenges may have been surmountable if Peskin wrapped his hands around the right message. Instead, one of Peskin’s key issues is frozen in time: protecting renters.

Tenant organizers, former lawmakers, and housing production advocates told The Standard that Peskin may be missing the mark touting rent control and “responsible density” as residents cite affordability as one of their top concerns (opens in new tab) and as the tenants movement itself is in a downswing. Let’s draw a distinction here: It isn’t that tenant protections aren’t needed or that Peskin’s work won’t help people. This is about what message is top of San Franciscans’ minds.

Peskin is campaigning on his tenant protection record — which is admittedly quite extensive — but it hasn’t launched him to the front of the pack.

One of his signature successes, rent control, is an easy example of a message that may have lost its shine. What help is preventing rent increases when you already pay half your salary just to hang onto your apartment?

Peskin’s political compass was forged in the fires of the first dot-com boom’s red-hot rental market. In 1999, a single phrase could send chills down a San Franciscan’s spine: Ellis Act eviction.

In a city that has mostly constrained landlords’ ability to evict tenants who pay their rent on time and who play by the rules, the state Ellis Act allows landlords to pull their apartment buildings off the market, often to sell them as condos. When tech workers first bum-rushed the gold in San Francisco’s hills, many landlords saw dollar signs in their eyes.

In San Francisco, tech booms are eviction booms. Rent board data shows evictions nearly doubling the year before each of Peskin’s most hard-fought elections, first in 2000, then again in 2015.

“There was this incredible consciousness that affected the politics of the city around protecting tenants during those years, and that is not true today,” said Randy Shaw, executive director of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic.

In those years, evictions were like a bat-signal, and Peskin was a vigilante swooping down to “BAM!” “ZAP!” “POW!” scurrilous landlords.

A quarter century ago, when Peskin’s hair was still jet black, the then-president of the Telegraph Hill Dwellers protected the area around a special hill known for wild parrots and stunning views. That led the burgeoning firebrand to rally alongside Asian American civil rights and housing groups — like the Asian Law Caucus and the Chinatown Community Development Center — to protect tenants of 1345 Grant Ave. against an infamous, headline-grabbing Ellis Act eviction (opens in new tab). Kwong Choy, a 65-year-old gardener, feared his family might be evicted not only from their apartment, but from the city altogether.

Peskin and the alliance of Asian American groups won. During his first campaign for supervisor, Peskin seized that momentum.

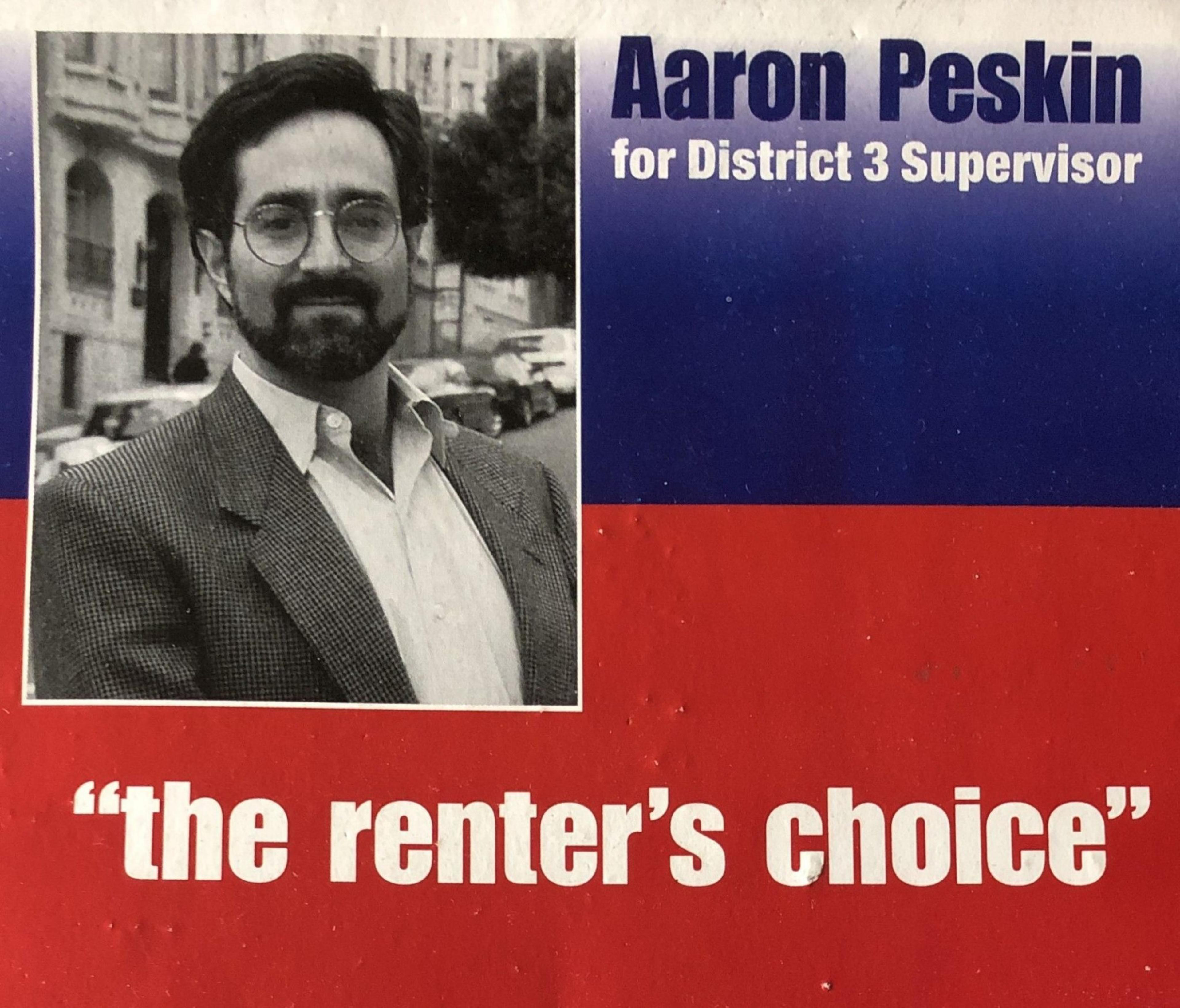

Peskin’s flyers dubbed him “the renter’s choice.”

“He’s the candidate who really got involved in the community. Who understands the community’s need for housing, quality of life,” said Wing Hoo Leung, president of the Community Tenants Association, who remembers Peskin’s long-defense of Chinese renters.

And make no bones about it: When he won, Peskin continued delivering for renters.

He cosponsored more than a dozen laws to protect tenants in his first two terms in office, many of which were successful: codifying tenants’ rights to distribute communications to other tenants to organize, limiting the amount of construction costs landlords could pass through to tenants, requiring tenants be paid when evicted under the Ellis Act, and more.

Peskin was the chief author of most of those laws. His competitors in the mayor’s race? Their legislative histories for tenants’ rights are as thin as an eviction slip.

But there’s a flip side to that record. And how San Franciscans view it would slowly shift over time.

In 1999, fighting developers — and the homes they would build — was broadly seen as anti-gentrification. Defending the little guy. The now-defunct progressive newspaper, the San Francisco Bay Guardian (opens in new tab) (may she rest in peace), even coined a word for the specter of towering developments: Manhattanization.

If Manhattanization was the villain, Peskin was King Kong.

In 1999, Peskin was president of the Telegraph Hill Dwellers, a neighborhood group swatting back development. In its newsletter, “Semaphore (opens in new tab),” Peskin touted the group’s latest win that year. “We saved the Colombo Building (at 1 Columbus Ave.) from the wrecker’s ball,” he wrote, preventing the construction of a condominium project. He trumpeted the Dwellers’ success enacting nearby 40-foot height limits to prevent dense development.

As supervisor, Peskin co-sponsored 2002’s Proposition D, which stripped some Planning Commission appointments from the mayor’s office, and gave them to the Board of Supervisors. It’s perhaps one of the most transformative moments in the city’s housing history, helping progressives pump the brakes on approvals for new home developments for the sake of public input. Then-Mayor Willie Brown clocked the measure as a choke point throttling new housing construction.

Brown called voters “ass-backward” (opens in new tab) for supporting the change. They had sided with Peskin.

Decades later, studies would show San Francisco takes as long as 34 months to approve new housing that other cities move forward automatically. California government would call out the ability (opens in new tab) for a single San Franciscan to stall the construction of new housing.

The housing affordability crisis flipped the anti-development conversation on its head.

As rent soared higher than the tilting Millennium Tower, affordability became the issue on tenants’ lips. San Francisco YIMBY harnessed that frustration (yes, aided by heaps of cash spent by developers (opens in new tab)) to promote a simple message: Build more housing and rental prices will drop. San Francisco YIMBY Organizing Director Jane Natoli noted Peskin never shifted his messaging to meet that new reality.

“I think that’s one of the challenges Peskin faces, right? He’s been around a long time. He knows a lot of people, so he’s shaped a lot [of politics], but those forces have also shaped him. And that makes it harder to cast yourself in a different light,” Natoli said.

Now, fighting developers isn’t seen as anti-gentrification by a broad swath of the electorate. Voters have — in large numbers (opens in new tab) — elected state Sen. Scott Wiener and Mayor London Breed on a message of housing production. Whether you agree with the argument or not, many voters now view fighting development as a backwards move that keeps rental prices high.

And today, not enough renters feel threatened by evictions to make Peskin’s renter-friendly record resonate.

Again, rent board data points the way. Evictions are far lower than they were during the twin dot-com booms that twice propelled Peskin to office — in fact, they’re down by roughly two-thirds. Since the pandemic, the rental market has largely cooled. There are fewer landlord-leery headlines, spurring fewer rallying activists to hoist “AARON FOR MAYOR!” signs.

California Working Party State Director Jane Kim, a former San Francisco supervisor and Peskin ally, wonders if progressives succeeded to their own political detriment. Is 2024 simply a cooler economic moment? Or did progressive Democrats write so many tenant protection laws that folks are not as energized to fight developers?

“I’ve been asking myself that question the last two years,” Kim said. On the issue of housing, “did we win everything that the voters had an appetite for on the progressive agenda?”

Whatever the reason, the current simmer in the tenants’ movement can be seen with your own eyeballs.

Just a few weeks ago in the Board of Supervisors’ ornate City Hall chambers, Peskin advanced legislation that may expand rent control from housing constructed through 1979 to housing constructed through 1994.

If the legislation were on the docket at the start of Peskin’s rise at the turn of the millennium, tenants would have packed the house. Activists would have overflowed into the hallways, blowing whistles and waggling picket signs.

Instead, tenant organizations sent supportive emails. Ten people sparsely dotted the pew-like benches in the Board of Supervisors’ legislative chamber.

After much political teeth-gnashing and an amendment to shrink its scope, the Board of Supervisors voted to back Peskin’s legislation unanimously, 11-0.

Ultimately, if California voters approve rent control reform, Peskin’s legislation may expand rent control to 16,000 more San Francisco tenants. It may be the most sweeping rental protection Peskin has authored — out of dozens of such protections — in 24 years.

Not a single tenant spoke on the effort’s behalf.

The silence speaks more to Peskin’s troubles than any poll shows.

Peskin himself acknowledges the rental dynamics that have been the wind at progressives’ backs.

“When people see their neighbors, who are part of their community, getting literally put out on the curb, it’s very immediate and it’s very visceral and it’s very real. And there’s less of that happening at this moment,” Peskin told The Standard.

But he contends the outsize political spending against him is juicing fear in the electorate, adding, “there are no billionaires spending millions of dollars telling everybody that they’re about to be evicted, but there are billionaires who are spending millions of dollars telling people that they’re not safe.”

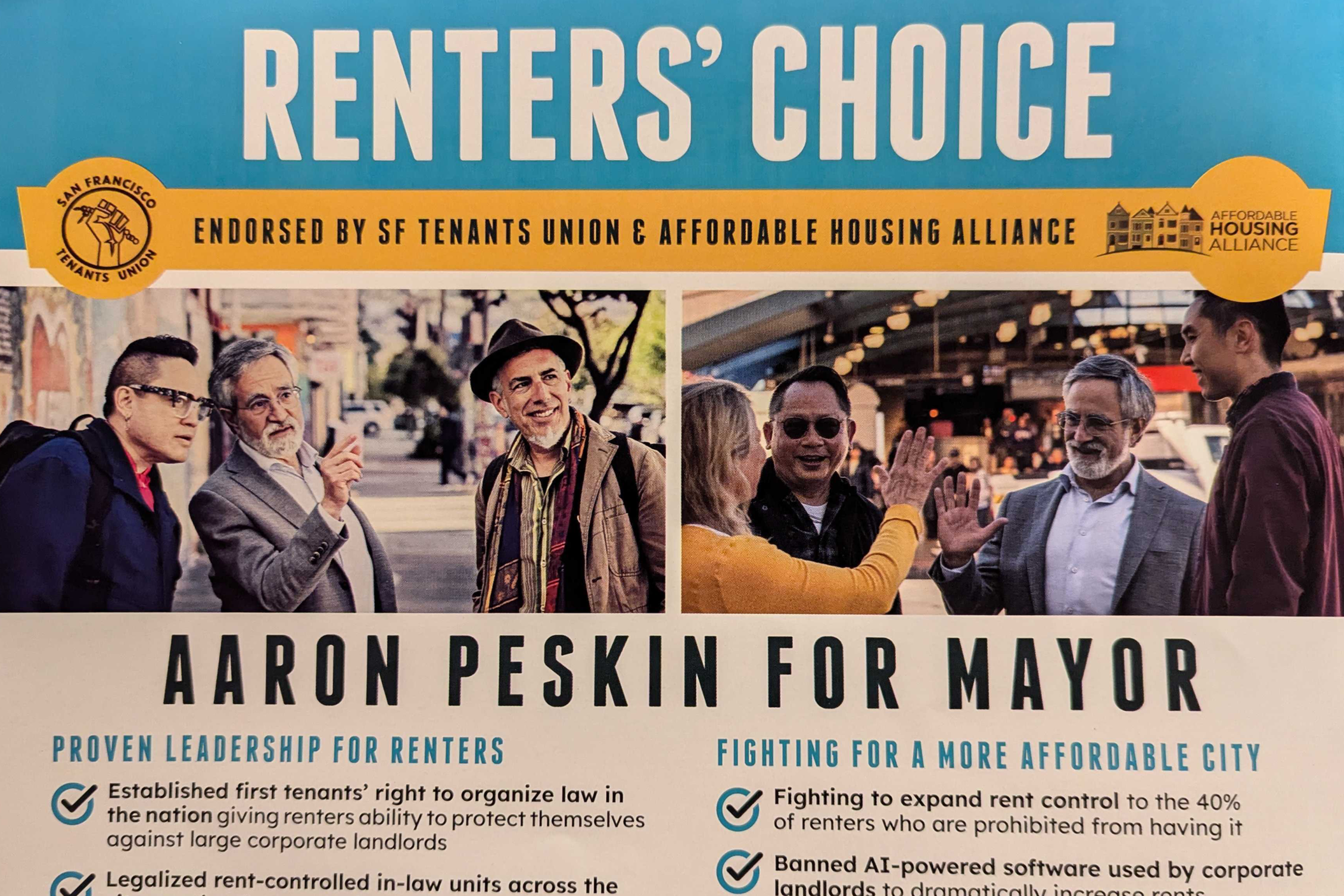

Despite billionaire opposition (opens in new tab), Peskin is as laser-focused on keeping tenants housed as ever. His tenant protection positions have hardly budged a single city block. As if to underscore that point, just last week, one of Peskin’s latest mayoral election mailers hit this reporter’s mailbox.

“RENTER’S CHOICE” was splashed across the glossy page — the same slogan he touted in his first race, 24 years ago.