Karen Kenyatta Russell has come a long way — and waited a long time — to soak up this moment. She sits on the edge of her front-row seat at McClymonds High School in West Oakland, peering through her tortoise-shell glasses at a pristine basketball court, newly adorned with the signature of her legendary father.

Tall like her dad and almost regal in stature, she wears a dress of Boston Celtics green and gold earrings in the shape of Africa.

“I just want to remind you guys we have a new gym floor, named after the great legend Bill Russell!” bellows Brian McGhee, master of ceremonies for the event Wednesday. “Give it up for Bill Russell, y’all. And on top of that, today is his birthday!”

Indeed, William Felton Russell would have turned 91 on this day. Karen says his closest friends still called her dad William up until his death three years ago. It would have meant so much to have him here at McClymonds — or Mack, as everyone calls it — for the ribbon-cutting, fittingly staged just two days before the NBA’s All-Star Weekend tips off in the Bay Area.

For Karen, this night is 63 years in the making. She has never before visited Mack, known for shaping many Black dignitaries like her father, to the point the school has taken on the name “School of Champions.”

She misses her dad on his birthday. His aura comes back to her through the unmistakable sound of sneakers pounding on polished hardwood.

Section 415: The Giants’ hire of Tony Vitello marks the start of a bold new era

Section 415: Ballers manager Aaron Miles on bringing a title back to Oakland

Section 415: Cricket is on the rise in the U.S., and the Bay Area is a hotbed

“I love the squeak of the shoe,” she says.

She also feels close to her dad sitting next to 93-year-old Bill Patterson, a mentor of Russell and plenty of other young men at McClymonds back in the day. “He smells like my dad,” she says. “The fingernails look like my dad’s fingernails.”

Today, Karen gets to see McClymonds at its best — proud, jubilant, and hopeful. She is only now learning of the persistent erosion of the school’s facilities.. McClymonds is hallowed ground in Oakland, but its disrepair, allowed to continue for decades by the Oakland Unified School District, cuts deep.

“The cavalry’s not coming,” Karen says, echoing the sentiments and fears of many West Oaklanders, who’ve watched the school’s enrollment drop to 280 from a high of more than 1,000.

To make this night happen for the family of Bill Russell, McClymonds received a surprise gift from another local basketball luminary, Stephen Curry. The Warriors star’s foundation with wife Ayesha, “Eat. Learn. Play.,” and his sponsor Under Armour quietly donated the gym renovation, complete with a new springy court donning Curry’s personal brand logo, shiny backboards, a fresh paint job, lights, scoreboards, and padding under both baskets.

But this beautiful new basketball court — one of 20 the Currys have built around the world, 11 of which are in Oakland — is only a basketball court. It’s not a new school. What comes next will determine if the generous gesture truly matters for McClymonds or if it’s just a feel-good, made-for-All-Star-Weekend tale.

The school district has promised McClymonds a $91 million campus-wide facelift. The long-overdue bond allocation would address the school’s lead piping, archaic kitchen equipment, and ripped-up football turf, among other essential improvements. Without them, the school’s shockingly low enrollment may wither further.

“We were trying to get the football field done for years, and we’re still waiting on that,” says McGhee, McClymonds’ community school manager, a 1985 alumnus who played football at Cal Berkeley. “We’ve been winning state championships. They gave us keys to the city, but what the hell is that, a piece of wood? I mean, what comes with that, you know?”

‘Used as a poster child’

A few weeks ago, Karen Russell picked up the phone in Seattle. It was Ben Tapscott, a long-retired McClymonds basketball head coach, calling with news that he had been dreaming of sharing for years.

“She had tears in her eyes,” Tapscott said.

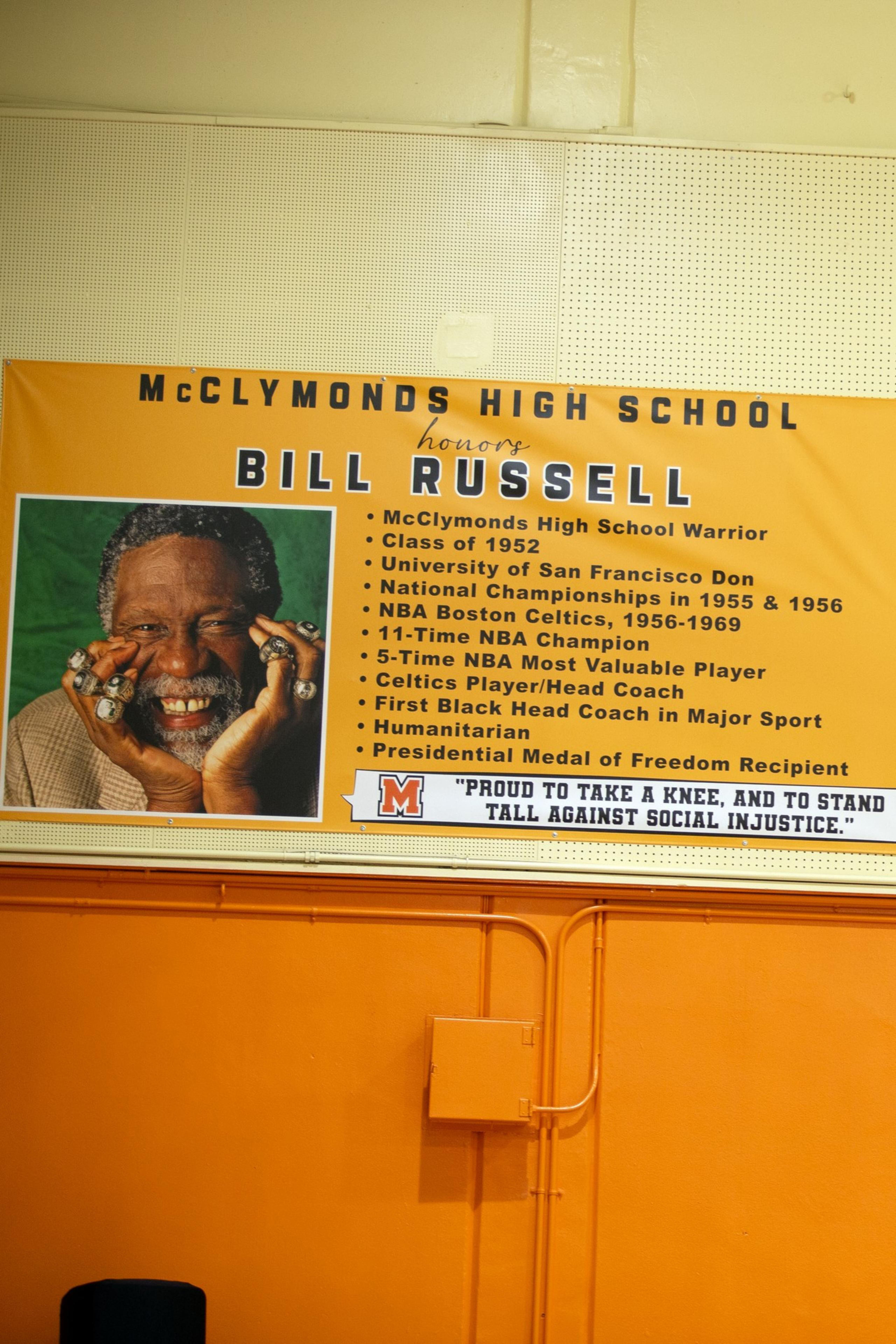

Bill Russell had been a living legend. The towering presence won two NCAA titles with the University of San Francisco and 11 NBA championships with the Boston Celtics, marched with his friend Martin Luther King Jr., and became the first Black head coach in the NBA. In 2010, President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

But this thing with McClymonds, where her father graduated all the way back in 1952, really meant something to Karen. She quickly decided that she and her brother Jacob would drive down from Seattle — where she moved to live with her dad at age 11 — to Oakland for the ribbon-cutting.

Her father, she said, “felt so strongly about McClymonds.”

To Karen, this wasn’t just about honoring her dad. It was about honoring the history of the Great Migration, the story of how her family rose from life under Jim Crow in Monroe, La., to Karen graduating with a degree from Harvard Law School.

West Oakland became one of the thriving meccas of Black culture, with McClymonds its beating heart, molding many people who shaped America: baseball Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, NBA star Paul Silas, rapper MC Hammer, and the first Black mayor of Oakland, Lionel Wilson.

Russell gave back to his alma mater by creating an endowment that helps every McClymonds student upon graduation. In 2008, he visited Mack to talk with the boys basketball team, which won the state championship, a discussion that lasted two hours.

Russell likely would not recognize much of the school in its current shape.

In 2017, Tapscott went to a football practice and saw head coach Michael Peters bringing water to the field from his mother’s house nearby. “He said, ‘Coach, the water’s no good. It’s got lead in it,’ ” Tapscott recalls.

Today, McClymonds has a water fountain and a kitchen sink covered by black trash bags (the school does offer a few filtered water options for students). Redoing the piping will be a big part of the renovation, which is expected to begin this summer, John Sasaki, the school district’s director of communications, told The Standard.

On a recent school day, Ginale Harris, whose son is a junior football player at McClymonds, showed a visitor around. In the cafeteria, she pointed out that while other Oakland high schools have lunch cooked fresh on-site, McClymonds has meals delivered and placed under warmers.

In the kitchen, she pointed to several mouse traps on the floor. Later, in a faculty kitchen area, she identified mouse droppings in the cabinetry.

Harris showed the Family Resource Center, an old classroom she had turned into a place for parents to come and be heard. She said Trader Joe’s donates fruit and other healthy items to stock the refrigerator for hungry students, who are often forced to order food on delivery apps like Doordash.

Harris recently showed all of this to a member of the Oakland Unified School District’s Citizens Bond Oversight Committee, a state-mandated group of local residents that oversees the $735 million in facilities bonds approved by voters. She attends all the committee’s meetings and remains unconvinced that McClymonds will ever see the promised $91 million. She’s not alone in her skepticism.

“I think [McClymonds has] been under assault for quite a while,” said VanCedric Williams, the OUSD school board representative from McClymonds’ District 3. “There’s been promises of renovation, and they’ve been used as a poster child to get bond funds to actually renovate the school, and then the superintendent at the time would redirect the money elsewhere.

“But the community has been very strong. The alumni have fought for the legacy, because it is the centerpiece of West Oakland.”

Williams said OUSD’s status as a “choice district,” allowing eighth graders to attend any high school in the city, has only weakened Mack. Due to gentrification and the dwindling reputation of McClymonds, Williams said, 60% of West Oakland residents attend other high schools.

Sasaki, the OUSD spokesman, said it’s “not true” that McClymonds hasn’t received bond money, citing smaller renovations that cost a few million dollars. However, when compared to peer schools like Fremont High School, which received a $133 million bond allocation in recent years, it doesn’t amount to much.

OUSD is waiting on “the final green light” from the Department of State Architecture to start the big renovation this summer, Sasaki said. He emphatically denied that OUSD would ever allow McClymonds to close its doors — a fear that is carried by many school supporters.

“We’re doing everything we can to boost the enrollment here,” he said. “Bottom line, this is a beloved high school.”

‘More like family’

Brandon Davis shouldn’t be playing basketball for McClymonds. For one, he lives with his mom in East Oakland, some seven miles away. And considering that most West Oakland kids aren’t attending McClymonds these days, Davis is truly an outlier.

Sure, his father grew up in West Oakland and went to Mack. But his dad was kicked out of the school, and he has not been present for most of the young man’s life. Davis could have easily picked his neighborhood school, Fremont, but there was something deeper pulling him across town.

“I told my mom, ‘This is where I want to go,’ ” said Davis, McClymonds’ senior point guard. “We’re more like a family here. With Mack, even though something might not be going right, we’re going to figure it out together.”

Sports teams that do more with less — particularly in football and boys basketball — have long been symbols of McClymonds’ grit. While this year’s Warriors have a pedestrian 11-15 record, they played only two home games due to the timing of the two-month gym renovation. They had to practice at the West Oakland Boys & Girls Club.

“Of course [the gym renovation] is nice for the future of Mack,” Davis said. “But just not having that Mack spirit when we [had] home games, that [was] really a disadvantage for us.”

The spirit returned in full force at Wednesday’s Senior Night, when the lights finally came on at Bill Russell Gymnasium. After a long season of feeling homeless, McClymonds’ eight seniors squeezed every last drop of enjoyment from the occasion. Before the game, Davis walked to half-court with an entourage, wearing a boa of faux dollar bills around his shoulders.

The Warriors would go out in style, dominating Skyline High from the opening tip. The near-packed house hooted and hollered throughout, outpouring a season’s worth of pent-up energy when Davis exploded through the air to swat away a layup attempt.

Davis would like to play basketball in college, like many McClymonds Warriors before him. To do so, he may have to go the junior-college route. Academically, he has already been admitted to San Francisco State, plus a few others. As the first in his family to go to college, he would be setting an example for his four younger brothers. He hopes to study sports medicine.

“They’re all looking up to me, and I got to set that tone,” Davis said. “So, I’m glad I stayed at Mack.”