On a sunny day in September 2017, hundreds packed into the Castro Theatre to sip White Russians, squeeze lime onto carne asada tacos, and pop back tins of Breez cannabis mints before a screening of “The Big Lebowski.”

It was a fitting party for San Francisco startup Eaze: wildly expensive and slightly stoned. The “Uber for weed” had just raised $27 million (opens in new tab) from investors, and the mood was electric.

“Look how far we’ve come!” Eaze cofounder and chief marketing officer Jamie Feaster said to the packed audience (opens in new tab). “This is awesome that we can be here celebrating marijuana with like-minded individuals.”

Four years before, Eaze was a half-baked idea discussed at Disneyland. By 2017, it was facilitating 120,000 medical cannabis deliveries (opens in new tab) a month. With California set to allow sales of recreational cannabis the following year, hockey-stick growth appeared inevitable.

Over the next few years, the company would rake in millions more from investors, expand to four states, and cinch a coveted position in the title sequence (opens in new tab) of the hit HBO series “Silicon Valley,” featuring tech darlings on their way to world domination.

But the high didn’t last long.

Eaze burned out on growth, trying to position itself for a green rush that never really came because of California’s bungled legalization rollout. Plagued by years of overregulation and high taxes, the conclusion investors and employees reached is that selling drugs is radically different than selling software. With duct-taped technology, the company decided to forge ahead anyway, bleeding through $350 million in the process.

By the time Eaze quietly filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy last month, a blunt rotation of CEOs had failed to save it, a web of competing lawsuits had been filed, and two former consultants were sent to prison. Now revived in a diminished form, the startup has traded eat-the-world ambition for a more sober outlook.

“It got really big, really fast,” Feaster said. “I tried, but I couldn’t course-correct it.”

Planting and watering

The idea for Eaze was sparked on a roller coaster — fitting for a company that sharply ascended to a $700 million valuation (opens in new tab) before plummeting back to Earth.

Keith McCarty — who struck it rich as an early employee of social media company Yammer — pitched his idea for on-demand weed delivery in a random conversation with Feaster at Disneyland. The two hit it off and discussed a startup while riding — and this is not a joke — Space Mountain late into the night.

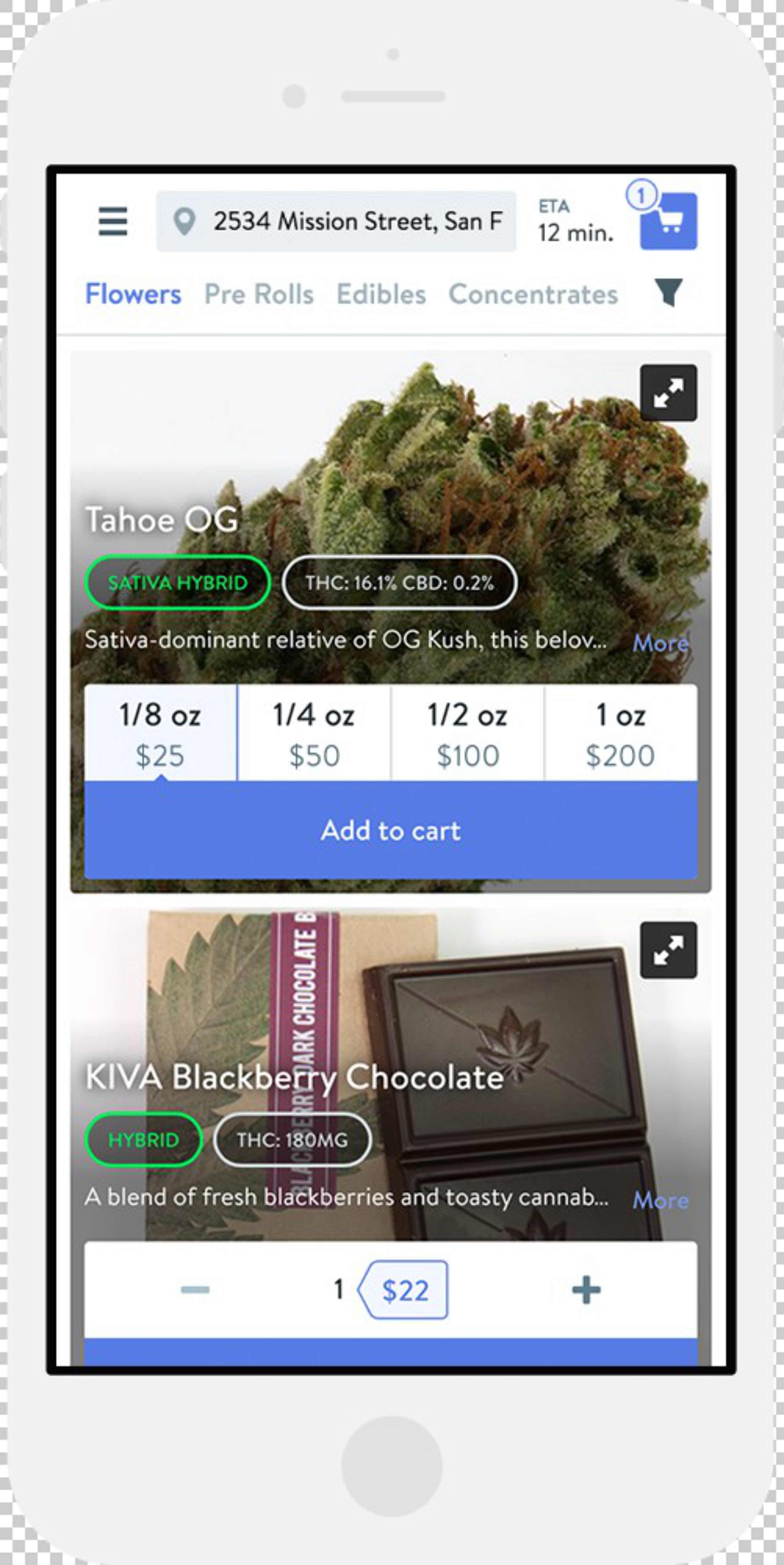

They regrouped in a SoMa coworking space above the Temple nightclub, where their desks would shudder when the DJ set began. The goal: replacing Ziploc baggies handed over in parking lots with a professionalized marketplace accessed through sleek technology.

On the day Eaze launched in the summer of 2014, Jimmy Kimmel gave the company free promotion by mocking it on late-night television.

“We’re finally living in the America Cheech and Chong always dreamed we would,” Kimmel said in his monologue (opens in new tab), referring to the stoner comedy duo. “Whoever pairs this with a pizza delivery app will probably get the Nobel Prize.”

San Franciscans flocked to the Eaze website. Users uploaded a photo of their medical license; chose from sativa, indica, or a hybrid; and paid for their fix. Within 10 minutes, a driver was at their door with the goods.

“Right when we came out of the gates, people were like, ‘We need this,’” Feaster said.

The company began chasing supercharged growth.

“The plan is to be in every market as quickly as possible that allows for medical marijuana and even recreational use of marijuana,” McCarty told Quartz at the time (opens in new tab). But the seeds of Eaze’s future problems were already being planted.

“What was crazy to me was just how fast the business was growing, while the actual user experience was broken in so many ways,” said Shri Ganeshram, an early Eaze investor who joined in 2015 to lead engineering as a member of the founding team.

Eaze’s original platform was built by contractors in Eastern Europe. The products listed on the buggy website didn’t match inventory, and wait times were often wrong. Ganeshram advocated for rebuilding the code base, but his pleas were ignored in favor of furiously pursuing more deliveries.

By the end of 2016, Eaze had raised $25 million, making it the most-funded (opens in new tab) cannabis technology company ever. Investors forecasted that California, the most populous state, was on the brink of a cannabis gold rush as voters legalized recreational use for adults and allowed commercial sales to begin in 2018. Eager to get in on the ground floor of the boom, venture capitalists turned on the money taps.

Root rot

The date that California would legalize cannabis sales and consumption, Jan. 1, 2018, was eagerly circled on calendars at Eaze. But when legalization arrived, it was a hot mess. Revenue dropped more than 60% within a few weeks as customers struggled to find legal dispensaries and gawked at the high taxes before moving back to the black market.

Eaze had spent the previous year preparing for a weed-topia. Jim Patterson, the new CEO, hired more software engineers and brought on lobbying staff, raising the headcount to 80. From a new office on Pine Street in the Financial District, the company juiced its advertising, plastering billboards and wrapping buses with the slogan “Marijuana has arrived.”

Signs pointed toward a windfall: Sales had grown 300% in one year (opens in new tab). Though it was burning through at least $1 million every month (opens in new tab), Eaze was rewarded with even more millions (opens in new tab) by the “growth at all cost” funding environment.

But licensing issues for dispensaries and the high taxes the state imposed on regulated pot choked sales, while frequent changes to rules around delivery zones, packaging, and transportation left Eaze scrambling. Even as California’s framework solidified, cities had their own regulations, complicating Eaze’s vision of quickly scaling in the state.

One compliance employee spent hours pulling up coordinates on Google Maps and holding a physical ruler to the screen to ensure that Eaze’s billboards weren’t within the prohibited distance of schools, police stations, or churches.

“We could never project the scale that Eaze could operate at,” said the compliance employee, who joined in 2017 and asked for anonymity because he still works in the cannabis industry. “The goalposts were consistently moving. We couldn’t have a North Star.”

Eaze had its first layoff a few months later, and by the summer, Feaster decided it was time to leave.

“There were conflicting visions of where to go next,” Feaster said, adding that he thought the formerly scrappy company had gotten top-heavy and was making big investments in unproven ventures.

Regulatory pressure intersected with flamboyant spending. The company moved into an opulent office in Four Embarcadero with wraparound glass windows and sprawling bay views. Celebrities like talk-show host Montel Williams, basketball player Matt Barnes, and the rapper Quavo dropped in.

For its Eaze Summit, the company flew staff and dispensary partners to the luxe Marina Del Rey Hotel in L.A., where NBA legend John Salley regaled the audience with stories of his cannabis use (opens in new tab). Expensive prizes, including an all-inclusive vacation to Hawaii, were doled out to employees.

“It was sunshine and rainbows,” said one external affairs executive who joined in 2018 and asked for anonymity because he still works in the cannabis industry. “Gold poured from the taps.”

However, under the shiny hood, Eaze’s technology was stuck in 2014.

An infrastructure engineer who joined in 2019 was shocked to learn that core technology was prone to breaking if more than 60 orders came in at once. Instead of fixing the backend, Eaze’s engineers were working on other projects.

“It was like lipstick on a pig, instead of addressing the elephant in the room,” said the engineer, who asked for anonymity to speak freely.

It wasn’t long before cracks started appearing in Eaze’s finances. After pitching investors that it planned to deliver $1 billion worth of cannabis in 2020, Eaze downgraded that figure to $412 million (opens in new tab), then to $190 million (opens in new tab). The company laid off 20% of its 170-plus employees and moved out of its swanky office. Things would have to change.

Reaping and sowing

As a cash crunch set in, the company decided it was time for a big pivot under yet another CEO. It would run its own dispensaries and sell Eaze-branded cannabis.

Eaze set out to acquire Green Dragon, a chain of dispensaries with storefronts in Colorado and Florida, that would make it the biggest cannabis delivery service in the country. Green Dragon’s owners — married couple Andrew Levine and Lisa Leder and his son Alex Levine — were given C-suite positions, two seats on Eaze’s board, and a 30% ownership stake.

The merger was fraught from the beginning.

“The Levines came in like a sledgehammer,” said the external affairs executive, who worked at Eaze for nearly four years. Churn accelerated among top executives, and rank-and-file employees lamented the change in company culture as Andrew, Lisa, and Alex — collectively referred to as “the Levines” — attacked Eaze’s lobbying, public policy, and social equity teams.

“The sentiment moved to, ‘Oh, this isn’t a cool, innovative startup. We’re just focused on being a profit mill,’” said the compliance employee, who was pushed out a few months after the Green Dragon acquisition.

The Levines paint a different picture. In a statement to The Standard, they said they were lured into the acquisition under false pretences.

“Our assets [were] stolen by merging with a predatory, financially unhealthy company,” they wrote. “We were used as a scapegoat for the reduction in force that was required to keep the company afloat.”

They added that as experienced cannabis operators who ran a profitable business, they tried to “save the company.” But Eaze had broken technology and leadership that “fought with us at every turn.”

Meanwhile, a scandal involving Eaze was playing out in a New York federal court. In 2021, Patterson, the former CEO, pleaded guilty to conspiring to commit bank fraud for a scheme to deceive banks into processing more than $100 million worth (opens in new tab) of payments for cannabis purchases. Patterson and two associates — who both ended up in prison — created dummy websites and corporations purportedly selling face creams and green tea to circumvent federal restrictions. Eaze was not charged in the case and said it cooperated with authorities.

The money that once came in so easily became harder to find without major strings attached. In 2022, one of Eaze’s investors, Netscape billionaire Jim Clark, provided a $36.9 million loan on the condition that he could take control of the company if it failed to meet monthly revenue targets.

“We became, by necessity, very much focused on cash flow,” said Cory Azzalino, the CEO at the time.

Soon after, the Levines were fired from their executive roles at Eaze and subsequently resigned from the board. They fired back in a lawsuit (opens in new tab), calling Eaze a sham company and alleging that its leaders “raided Green Dragon for their own personal gain.” A month before they were terminated, the three sent letters to Eaze’s HR department complaining of a hostile work environment, intimidation, and gender discrimination, according to the lawsuit, which was later dismissed.

Without prospects for a major sales recovery, Eaze defaulted on the loan from Clark, and he foreclosed. In August 2024, he purchased Eaze’s assets at a public auction for $54 million — but not before the Levines filed another lawsuit (opens in new tab) claiming they were improperly denied access to company records, an allegation that Eaze denies.

Last month, the company declared bankruptcy, listing zero in assets — Clark had purchased the entirety — against $3.6 million in liabilities. The $350 million that Eaze raised over its decade of existence was gone, its promises to employees and vendors declared null and void.

But Eaze isn’t dead. In a move the Levines allege has “allowed the new company to dodge prior business debts and obligations,” its assets have been packaged in a new form.

Eaze Inc., a reincarnated version, has operations as a retail and delivery service in California, Colorado, and Florida, with $10 million in funding from Clark. Azzalino, CEO of the new entity, denies the Levines characterization of the transfer of assets. Clark’s loan, he said, was unanimously approved by the board and all classes of shareholders.

He said the original company failed because of a combination of internal missteps and California’s overregulation and overtaxation of cannabis.

“What happened is we raised way too much money at way too high valuations on the premise of growth that couldn’t come because of the regulatory framework,” he said.

The new Eaze, Azzalino said, will have a different trajectory.

“This is a put-your-head-down-and-grind situation,” he said. “This is not a hyperbolic growth story.”

That pitch won’t excite investors chasing meteoric growth. But it might just be the clearheaded mindset needed in an industry that bears little resemblance to a fun escape.