Welcome to The Looker, a column about design and style from San Francisco Standard editor-at-large Erin Feher.

Ruth Asawa couldn’t hide her rising anger.

As her youngest son, Paul, proudly showed off the hand-traced turkey drawing he had completed at school, Asawa was taken aback. It was autumn 1967, and Paul attended Alvarado Elementary, just down the block from their Noe Valley home. His mother was already a nationally recognized artist with pieces in the Museum of Modern Art and the collections of the Rockefellers and architect Philip Johnson. To Asawa, who had studied with Robert Rauschenberg, Josef Albers, and Willem de Kooning, the turkey was an abomination.

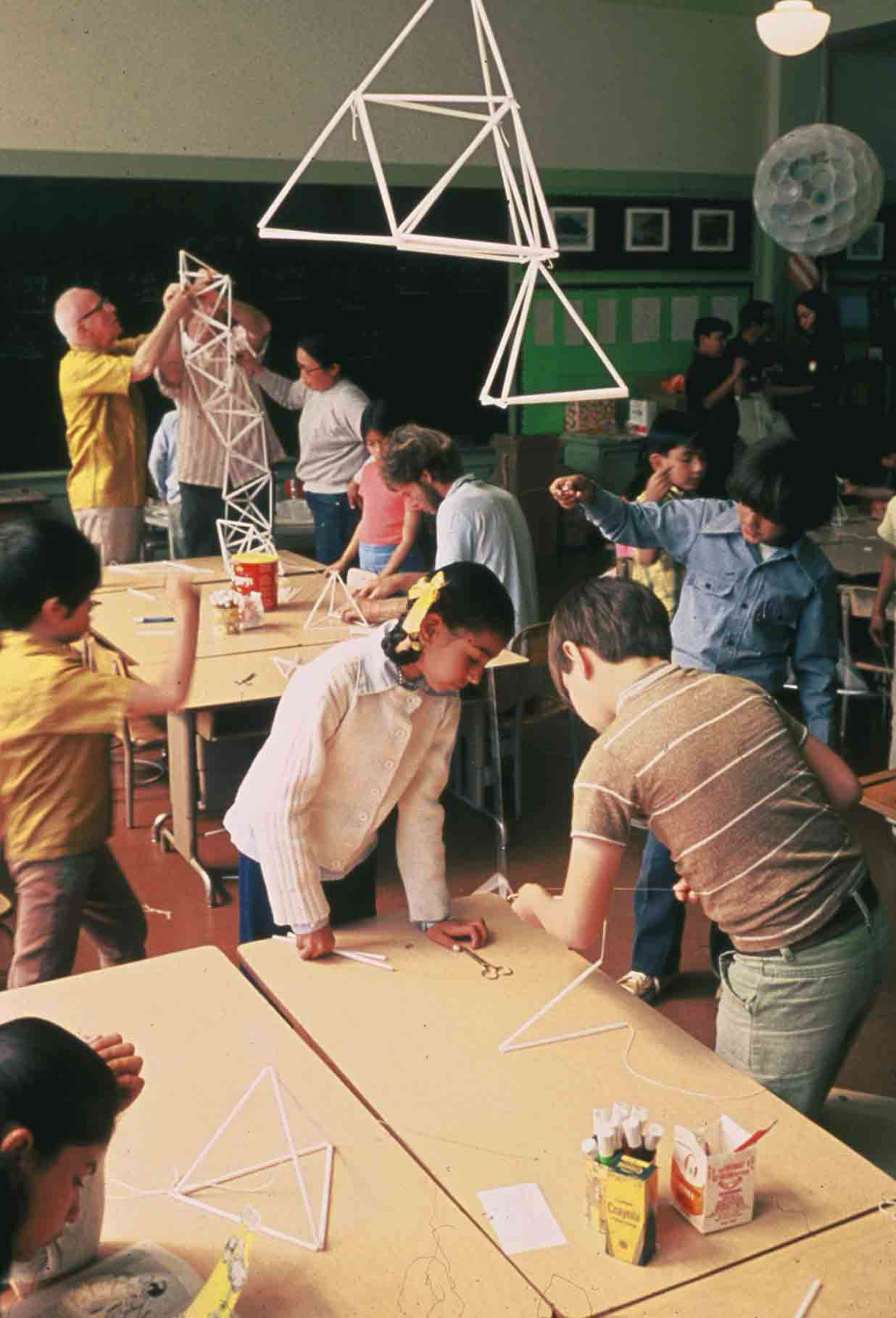

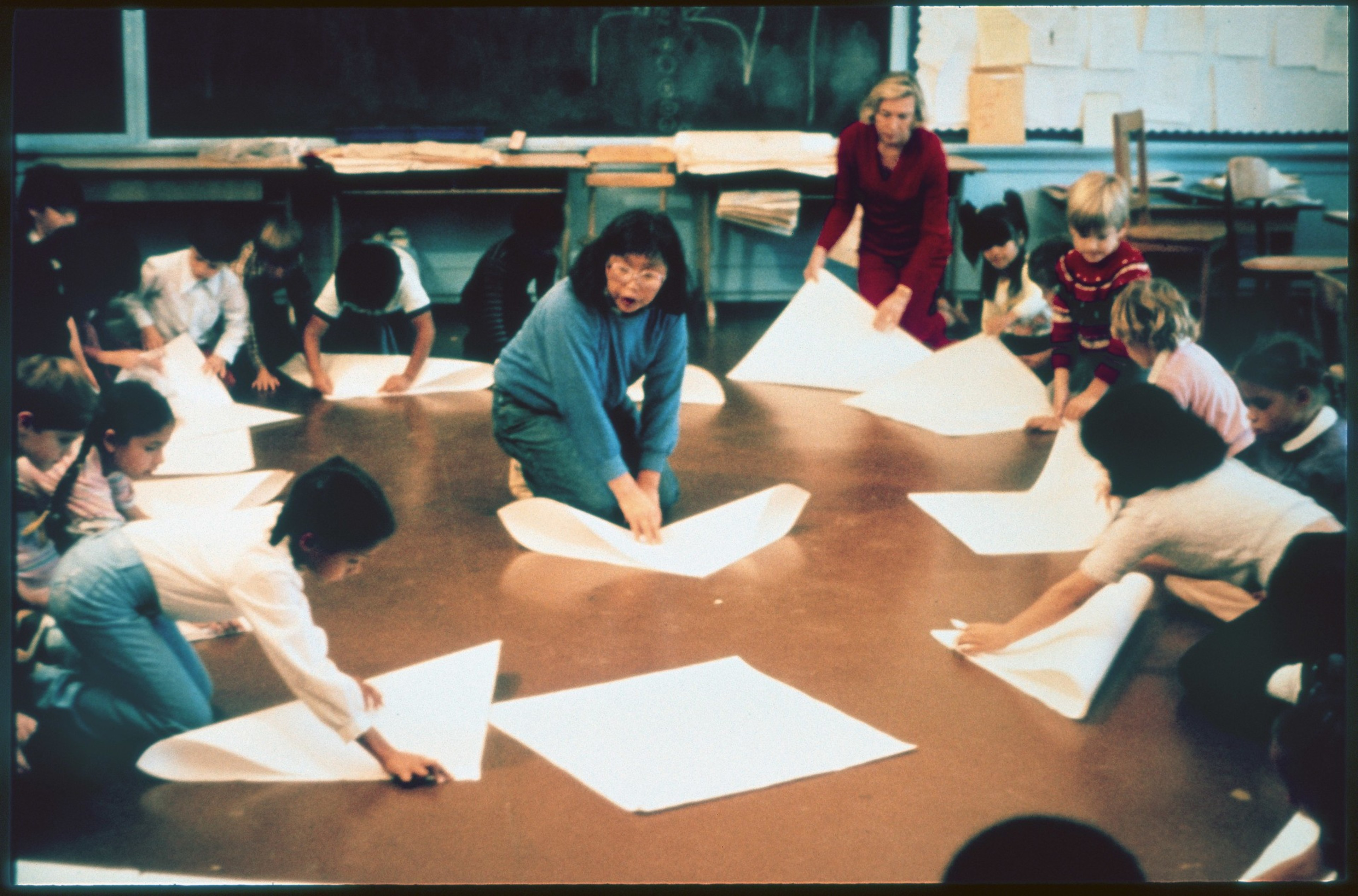

Asawa acted swiftly, rounding up a small cohort of fellow mothers and PTA members to elevate the arts program at the school. Calling themselves the “Valley Girls,” they scrounged up $50 in donations and launched an experimental summer school in the cafeteria, run completely by volunteers. Students were taught to weave on looms made from packing crates and to make sculptures from papier-mâché.

Ten years later — a decade of advocacy and thousands of hours of volunteer work — the Alvarado School Arts Workshop had a district-approved budget of $427,000. The program had spread to 50 San Francisco public schools, employing artists, musicians, and gardeners and recruiting thousands of parent volunteers. And it helped move thousands more families to opt into the city’s public schools.

“She went down to the school and started the program,” recalls Susan Stauter, the former artistic director of SF Unified School District and a close friend of Asawa, who died in 2013 at 87. “And then, bit by bit, she revolutionized it.”

Today, Asawa’s artistic legacy is cemented, especially in San Francisco. The School of the Arts high school bears her name, and a retrospective of her work (opens in new tab) fills an entire floor of SFMOMA. It is on view until Sept. 2, when it will move to MoMA in New York before being shipped off to the Guggenheim Bilbao in Spain. A collection of her deceivingly delicate-looking woven metal sculptures has a permanent home in the de Young’s Hamon Observation Tower.

But much of her most valuable work isn’t on view at a museum.

‘We need to do more’

On a sunny day this spring, 20-some kids tumble out of Alvarado Elementary’s ground-floor art studio into the yard. Almost every surface of the enclosed terrace glitters with rainbow-colored tiles, nearly 60 years’ worth of murals assembled by thousands of students, parents, teachers, alumni, artists, school nurses, and janitors.

Asawa and artist Nancy Thompson started the mural-making tradition back in 1970. A new work has been added approximately every six years, ensuring the inclusion of every child who attends kindergarten through fifth grade.

The most recent of these murals, a three-story aerial scene of hot-air balloons and rocket ships, was completed just a few weeks ago. An exuberant ceremony featured all the students, (opens in new tab) dressed color-coded by grade and arranged in a rainbow, jumping and cheering at their community’s accomplishment.

“Art really does bring joy to kids,” says Michael Wantorek, Alvarado’s full-time art teacher. “I have parents who tell me that the day they have art class is the one day they can get their kid out of bed on time.”

It’s easy to see why kids would be eager to get to Wantorek’s studio. Sun-drenched and set with large work tables ringed by candy-colored stools, it has art everywhere. There are posters of Asawa’s sculptures, Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits, Albers’ monochromatic squares, and William H. Johnson’s dancers, mixed in with hundreds of pieces of children’s art.

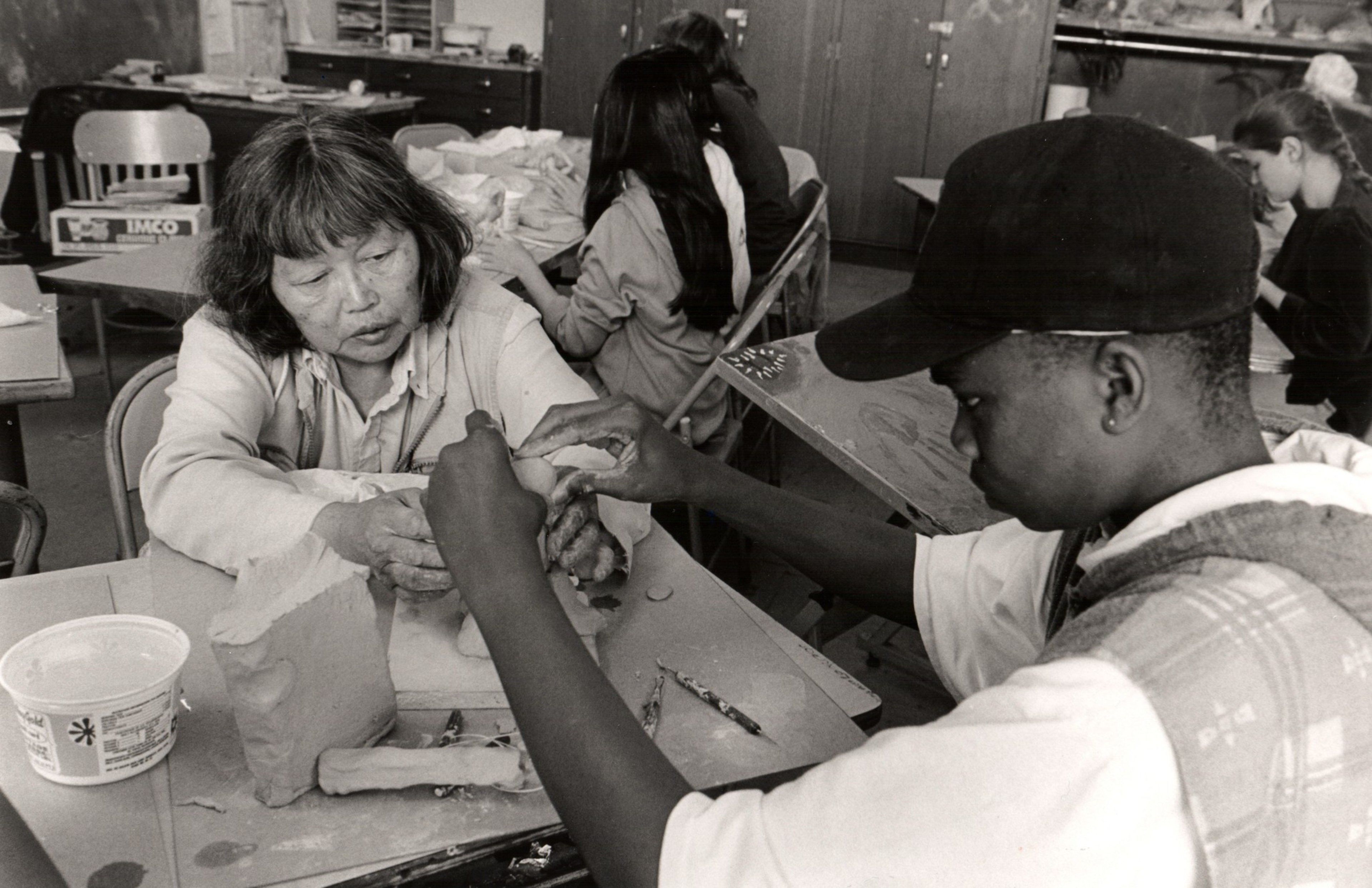

The back wall is covered with a long shelf filled with every art supply imaginable. A portly kiln squats in the rear, its lid popped to reveal a congregation of crocodiles rendered in soft pastels. “They will get their shine once we bake them,” explains Wantorek. The ceramics studio is yet another Asawa legacy.

“My mom was a bulldozer. The things she really wanted, she got them done,” says Paul Lanier, the creator of that maligned turkey art, who attended the earliest Alvarado School Arts Workshops as a student. He went on to study ceramics in New York, returning to San Francisco to teach at Alvarado for nearly a decade as one of the school’s many artists-in-residence.

His oldest sister, Aiko Lanier, taught there as well, rolling her art cart through the hallways. “It was really a magical, golden time for Alvarado, and so many of the schools.”

Asawa was a master at putting things together. As dexterous and nimble as she was with wire, she was equally skilled at weaving together coalitions of people in service of a cause. She convinced her artist friends to teach 8-year-olds; parents to hoard milk cartons, wood, fabric, yarn, and paper to stock the supply closet; and, eventually, the city’s most powerful philanthropists to open their wallets to pay for programs such as the Youth Arts Festival, in which children’s art took over the galleries of de Young Museum one week a year.

“You’d walk into a gallery and see your child’s painting of a butterfly on the wall, and upstairs you’d see children dancing. And over there, you’d hear a student orchestra. On Tuesday night, you could go and hear student poetry — the best of the best read their work,” Stauter recalls of the program held at the de Young from 1986 to 2020.

Asawa’s advocacy mirrored her creative practice — she embraced risk, experimentation, and getting her hands dirty. Her ambitions were never hers alone but required the buy-in of everyone around her. For every success, there could be a stumble. Asawa liked to tell the story of when she brought in the famed architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller to teach at the School of the Arts. When the bell rang, Fuller was mid-lecture, but the dazed students got up and walked out.

“My mom set a very high bar. She wanted [Francis Ford] Coppola to teach media, she wanted [Richard] Diebenkorn to teach painting,” says Lanier. He recalls the ceremony when then-mayor Gavin Newsom presented Asawa with the first-ever Arts Advocacy Award. “He said all these wonderful things about her, how she has contributed so much to arts education in the city. And she just replied, ‘And we need to do more. Much more.’”

‘The battle rages still’

Today, in part because of Asawa’s lifelong advocacy, every one of SFUSD’s 20,000 elementary students has access to a credentialed art teacher, and 14,000 middle and high school students are enrolled in one or more of five disciplines: dance, drama, music, media arts, and visual art. As budgets were examined and painfully trimmed throughout the school district over the past few months, line items for the arts remained miraculously untouched. As with most miracles, there’s a reasonable explanation behind it.

Recent state and local bonds and propositions have not only brought in significant arts funding but imposed stronger restrictions around how it is used, said Ron Machado, director of the SFUSD arts department. With the 2022 passage of Proposition 28, which dictates that 1% of California’s budget go toward the arts, the state began sending $17 million to $18 million directly to the SFUSD art department each year, much of it for hiring full-time teachers. That’s in addition to about $8 million per year in arts funding that comes from an earlier city bond measure that enshrined the Public Education Enrichment Fund (opens in new tab) through 2041.

“We are knocking on wood, but this money is pretty strapped in for the arts,” says Machado. “People are drooling over it, but they’re realizing they can’t touch it.”

It’s a rare bright spot in the gloomy financial outlook for SFUSD, which has a $113 million deficit and has threatened to eliminate any program or position not in service of “keeping the lights on.” (opens in new tab) Other programs spearheaded by Asawa are stagnant or at risk of shuttering.

The Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts, which she founded in 1982, still operates out of what was supposed to be its temporary home, tucked away in Twin Peaks. The hundreds of millions of voter-approved dollars raised to move it into a state-of-the-art building at 135 Van Ness, where students would be steps away from the city’s symphony, ballet, opera, and jazz center, have all been spent elsewhere. And Scrap, the nonprofit Asawa cofounded in 1976 to collect overstock paper, fabric, and other cast-off materials and redistribute them to artists and teachers, is losing its lease from SFUSD (opens in new tab).

Stauter, who says Asawa’s words come to her often, knows the artist would spring into action in a moment like this. “We’re living in a time, especially under Trump, where the arts are suffering,” she says. “The battle rages still to value and maintain the fight for access and equity and arts education in the public schools. But very importantly, Ruth would not give up hope.”