Lori Fogarty had just arrived at her desk at the Oakland Museum of California the morning of Oct. 16 when staff notified her of a break-in at the facility’s storage depot.

The 100,000-square-foot warehouse, which holds more than 2 million historical artifacts, had been hit overnight by a heist.

“I didn’t know, at that point, the severity of it,” said Fogarty, the museum’s director.

Laptops and cameras were taken. Cabinets had been rifled through and looted of precious metals and pearls. Storage bays that secure priceless Native artifacts had their doors wrenched open and their contents emptied.

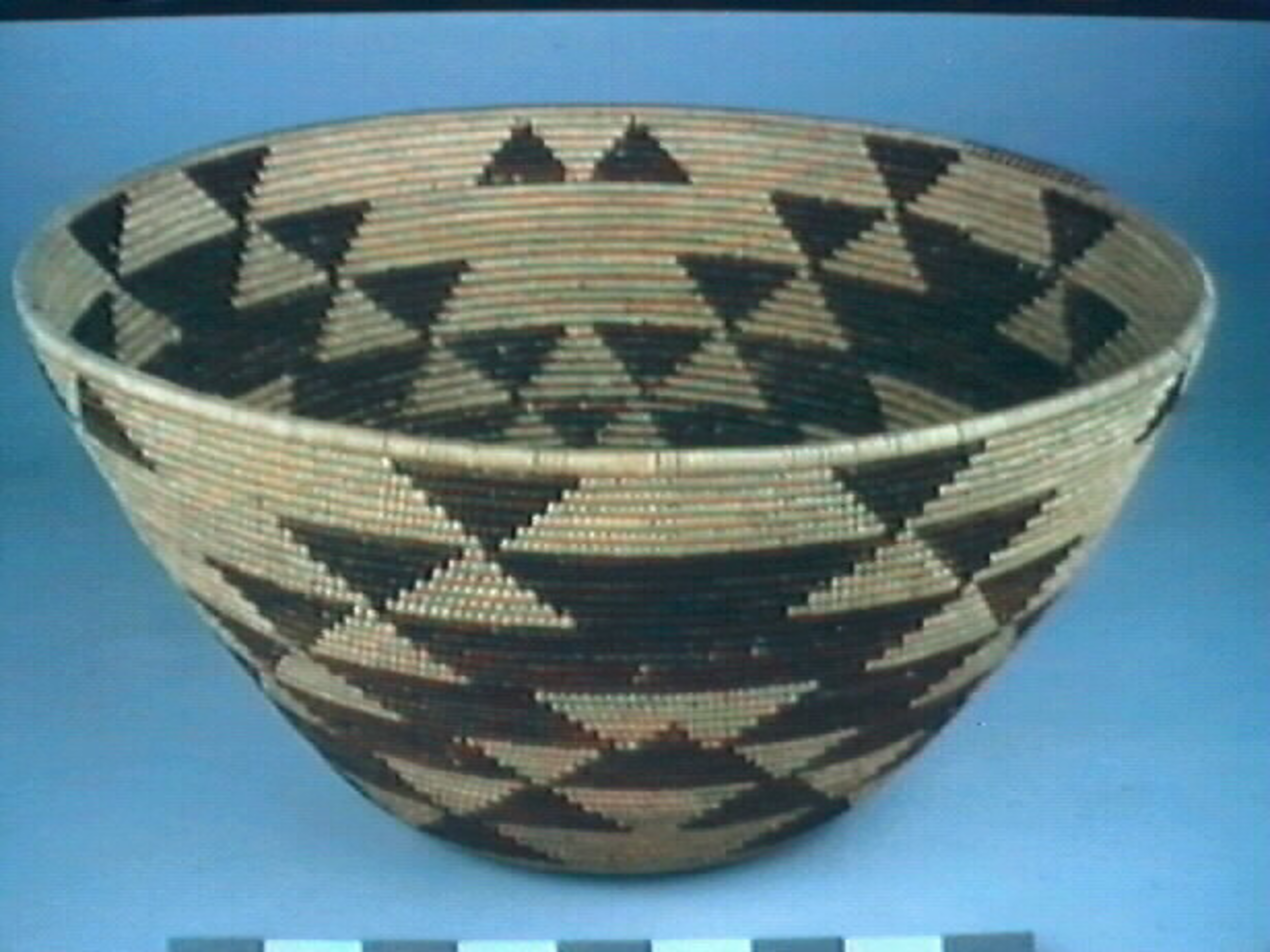

Just before 3:30 a.m., the thief or thieves — it’s unclear how many were involved — entered the facility and made off with more than 1,000 items from the museum’s collection, including jewelry, Native American baskets and tools, antique daguerreotypes, and a seemingly random collection of ephemera such as political pins.

“This is our shared cultural legacy,” Fogarty told The Standard. “In almost every case, the vast majority of our collection comes to us by gift, and we take it on as our responsibility to preserve it in the interest of the public and in the interest of the community. That’s why we want to put the word out to the community that this has happened and we’re hoping for help.”

The museum has linked with the Oakland Police Department and the FBI’s Art Crime Team, a specialized unit that will lead the investigation and alert local auction houses, pawn shops, and antique dealers in an effort to prevent the stolen artifacts from being fenced.

The OPD and FBI did not respond to requests for comment.

Details of the museum’s storage facility are kept private, and only a select number of staffers, including security guards, are authorized to work at the site. Security staff were off duty at the time of the heist, according to Fogarty.

The museum declined to explain why no guards were on duty that night or whether guards typically work overnight but said employees are not being investigated as suspects.

The thieves did not enter through a door, according to Fogarty, who declined to provide details, citing the ongoing investigation.

Fogarty said the OPD waited 14 days before announcing the burglary to avoid jeopardizing the investigation. When asked if detectives had hit a dead end, Fogarty demurred, saying the information was released to alert the public if artifacts end up in antique stores, pawn shops, swap meets, or flea markets. The hope is that shop owners or citizens will notify authorities.

“These thieves may not even really understand what they have and may be trying to dispense with them quickly and in various places,” said Fogarty. “They’re canvassing those types of locations, but they were really thinking that people would help be additional eyes and ears on the distribution of some of this material.”

The museum said it is in contact with the Northern California tribe affected by the theft. The tribe requested anonymity.

This is the third time in 15 years that OMCA has been targeted by thieves. In 2012 and 2013, the museum suffered two high-profile burglaries inside its Gallery of California History. In the first instance, display cases were smashed and an antique six-barrelled pistol and gold nuggets were stolen. Two months later, the thief returned, using an axe to break into the museum and shatter two glass display cases, making off with items from the California Gold Rush exhibit, including an 1870s gold jewelry box valued at $805,000 and a gold-mining scale.

The crimes were later connected, and police arrested Andre Taray Franklin. He was linked to both heists through DNA found on an axe cover left at the crime scene. The pistol and gold nuggets were never recovered, but investigators found the jewelry box, which Franklin had sold to a business owner for a mere $1,500. Franklin was convicted and sentenced to four years in prison.

News of this month’s burglary comes at a time of global frenzy around art heists. Just four days after the OMCA break-in, a team of thieves in Paris used a truck-mounted furniture lift to reach a second-floor gallery of the Louvre, pulling off a brazen daytime heist and vanishing with France’s crown jewels. As of Wednesday, two of the Louvre heist suspects had been apprehended, with two more believed to be at large.

But unlike the Louvre heist, where thieves made off with eight priceless pieces of jewelry, a smash-and-grab job like the one in Oakland, where a large swath of artifacts are stolen, indicates a more amateur approach, according to Alexander Eblen, a senior jewelry specialist and senior vice president with Christie’s in New York.

“Most of the time when you’re dealing with large-scale theft like this, you’re not typically dealing with the most sophisticated thieves, and you can have things of significant value selling for whatever they can get for it,” he said. “Juxtapose that with what was stolen from the Louvre, and those are the most valuable stolen items in a great long time. I think those people knew exactly what they were stealing.”

Eblen added that reselling jewelry of the kind stolen from OMCA, which is valuable not for its gems but for its historical merit, has become extremely difficult.

“With all the information sharing, this would have to be shuffled off into a nefarious private collection very quietly for it not to raise alarms,” he said. “It’s not impossible, but it’s harder for that to go unnoticed. As soon as it changes hands, there is no honor among thieves.”