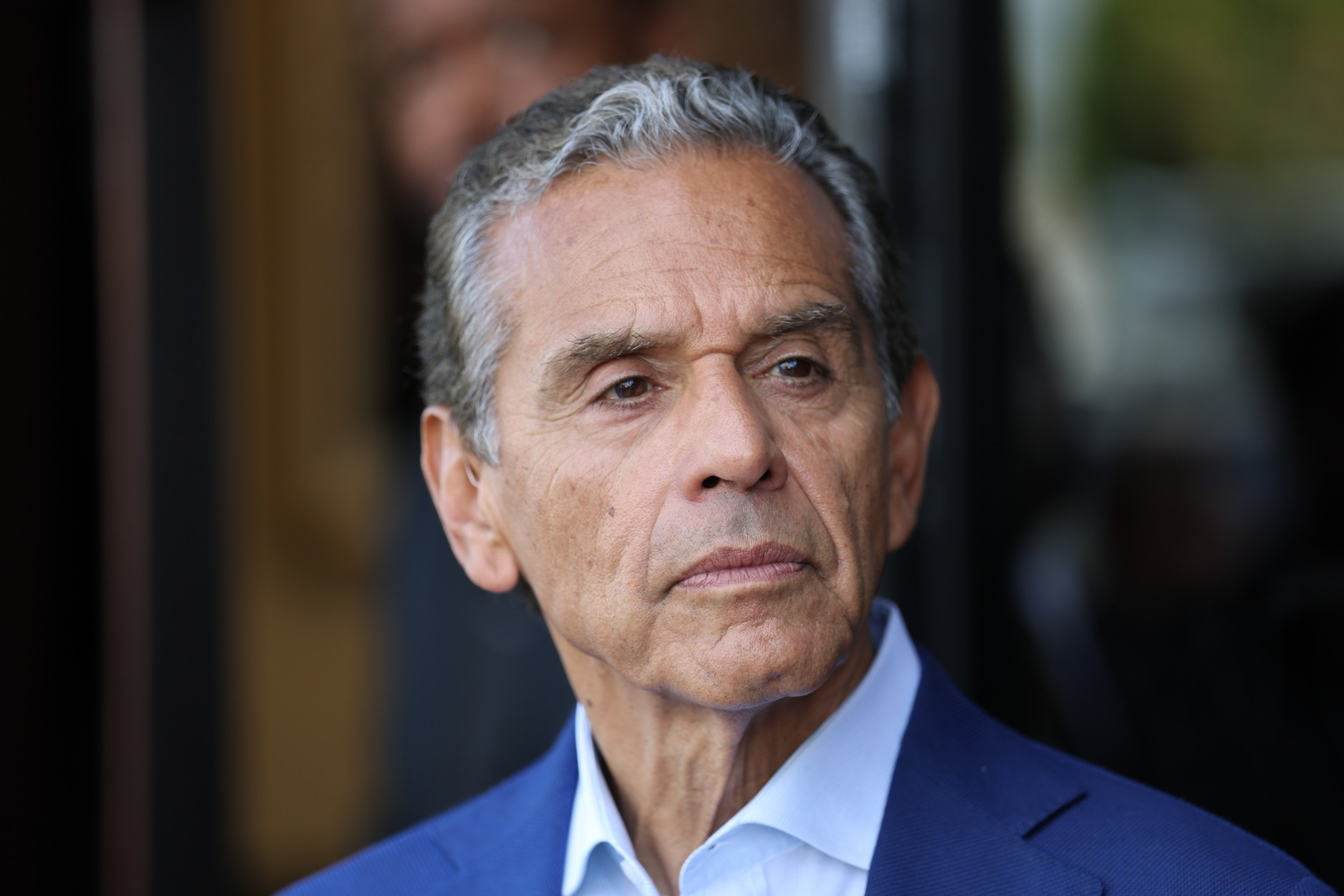

Stephen Cloobeck, the 64-year-old timeshare millionaire and two-time “Undercover Boss” star, would really like me to look at the picture of the naked Black man on his wall.

We are standing at the heart of his 16,000-square-foot mansion in Beverly Hills — a domicile so big the city briefly blocked it from construction (opens in new tab) — discussing his longshot bid for governor of California. A prolific Democratic donor, Cloobeck announced his entry into the crowded field to replace Gov. Gavin Newsom last year by declaring himself a “conservative Democrat” and deeming his fellow candidates too weak and too woke for the job. Maybe 30 minutes earlier, I’d asked him what exactly differentiates him from a Republican. Which is why he wants me to look at the photo.

The image is truly massive, at least 6 feet wide, and hung in a thick, black frame in the center of a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf in Cloobeck’s office, which is otherwise filled with framed photos of him posing with politicians and celebrities. It is black and white, and jarring in its gruesomeness, depicting the man from behind, standing in a river, hoisting a Klu Klux Klan member in a noose. Cloobeck gestures at the image proudly, as if to say, I told you so.

“See why I’m a Democrat?” he asks. “Who else would have that hanging in their office?”

If it was not already clear, Cloobeck is not running a traditional campaign for governor. The former real estate developer and founder of the timeshare behemoth Diamond Resorts International launched his candidacy at a 2024 election-night watch party at his home, surrounded by celebrities such as Zac Efron, Jeff Ross, and Casey Affleck. (The party’s ill-timed overlap with Donald Trump’s victory resulted in a paparazzi photo (opens in new tab) of at least one of these celebrities leaving the launch party looking incredibly dejected.) Most California political types learned of Cloobeck from a stunt he pulled at the state’s Democratic convention in May, when he paid more than 200 young people to attend in T-shirts bearing his campaign slogan, “California, get a Cloo.”

In the year since he declared his candidacy, Cloobeck has sued a Republican rival for violating state campaign finance law; sued a Democratic rival for trademark infringement; taken out millions of dollars in ad buys in states like Texas, New York, and Florida; and stormed off the stage of a major union event when another candidate spoke negatively about millionaires and billionaires. He recently made a cameo on “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” to do the nae nae (opens in new tab) with his friend Tiffany Haddish.

The results have been middling at best. Despite the dramatics, Cloobeck continues to poll at the bottom of the crowded field for governor, behind figures such as fellow businessman Rick Caruso, who has not even entered the race. The most common question I received when telling people I was writing a profile of Cloobeck was: Who?

But Cloobeck is poised to be an influential figure in the race regardless of whether anyone ever learns his name. With tens of millions of dollars at his disposal and an inside line to politicians like Newsom — whom Cloobeck calls “a friend” — the businessman could easily play kingmaker, even if he doesn’t get to be king. And if the last decade has taught us anything, it’s that we underestimate a rich man with daddy issues at our own peril.

So I dutifully went to his L.A. mansion to find out how seriously — and literally — California should take Stephen Cloobeck.

My interview with Cloobeck starts so quickly I almost forget to start recording. It is a Thursday afternoon in September, and we are standing in the foyer of his chateau-style mansion — a circular, marble-tiled room flanked by twisting staircases and lit by a massive skylight that opens onto a cascading chandelier of clear glass butterflies.

I am greeted by Elsa Ramon, his communications director at the time; Mabel Arrambide, his chief of staff; and Oliver, a fluffy white dog whose breed I cannot remember but am assured is very rare. Then Cloobeck saunters into the room, wearing his customary light-wash jeans and black T-shirt, and grasps my hand familiarly. I tell him he has a nice house, and he responds by listing off all the awards it has won.

He guides me into the living room, an enormous expanse equipped with a handcrafted Hungarian grand piano, a crystal chandelier, and a 22-foot-long dining room table covered in copies of his book, “Facing Hard Truths.” And now I am recording, because now he is giving me his life story: How he grew up here, in the San Fernando Valley; how he was studying to become a surgeon and then decided to go into real estate; how he took classes at Cal State Northridge to learn accounting, and then business law at UCLA; how he went into commercial real estate development and opened shopping centers throughout California and then built his first hotel in Las Vegas at age 29.

After that was when he first considered running for governor of Nevada, he tells me, except his good friend, the late Sen. Harry Reid, pulled him into a room with his other good friend, former Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak, and told them both that Sisolak should run instead. No matter. Instead, Cloobeck bought a struggling timeshare company called Sunterra, combined it with his hotel in Vegas, and created one of the country’s biggest timeshare companies at the time.

“I fixed the most broken of companies. Nobody could fix this company,” he says, in what can only be described as a Trumpian cadence. “It’s in my first book. I’ll give you a copy.”

We move down the stairs, past a wall filled with gold-framed news clippings and pictures of Cloobeck and his famous friends: golfing with Barack Obama, shaking hands with Bill Clinton, golfing with baseball legend Ernie Banks, shaking hands with Clinton again. There is a framed menu from a fundraiser he hosted for Obama, a framed front page of The Orange County Register announcing his entry into the race for governor, a shirtless photo of someone — him?? — oiled up and flexing, and a printed-out text message from Reid expressing his love and admiration.

We reach the bottom floor of Cloobeck’s house — a cavernous space filled with signed sports jerseys, several guitars, a drum set, and a neon sign designating it “Clooby’s Cave” — before he gets to the reason he decided to run for governor.

Which is, essentially, because everyone else sucks.

“I interviewed every single candidate,” he tells me. “I interviewed everybody, and I said, ‘This is the best we got?’” Kamala Harris, who was still considering a run for governor when he entered the race, was “a good prosecutor, but she was battlefield-promoted to her jobs.” Katie Porter, the former U.S. representative from California, has “never signed the front of a check.” Even Sen. Adam Schiff, whom Cloobeck supported in last year’s primary, wouldn’t be qualified if he wanted to run. “I don’t think Adam would be a good governor,” he says matter of factly. “He doesn’t have the executive experience.”

Which is why Cloobeck felt called to run. “I shouldn’t be here,” he tells me, not for the last time that day. “But those that are running for office right now, I would not trust with our life safety, I would not trust with our taxpayer dollars.”

The whole story seems oddly reminiscent of another old, wealthy, white man; of a fellow real estate developer turned reality TV star who got a leg up from his father, who speaks off the cuff and to the frequent chagrin of his advisers, and who donated to Democrats for decades before deciding they were unfit for office.

But I don’t need to bring the comparison up, because Cloobeck does it himself.

“I’m the Donald Trump of the Democrats,” he tells me with a grin. “It’s a truism.”

The phenomenon of rich people running for office didn’t start with Trump, of course — in California, it is a time-honored tradition. Talk to political insiders in the state, and they will rattle off a graveyard full of failed gubernatorial campaigns run by multimillionaires: Al Checchi, the airline magnate whose cadre of high-priced political advisers couldn’t help him beat Gray Davis for governor in 1998, or Meg Whitman, the former eBay CEO who spent $140 million to lose to Jerry Brown in 2010. Perhaps it is something about being a state of dreamers — a place where people go to find freedom or stardom or gold. Perhaps it is because there are simply so many rich people here, and only so much to do.

“This is the curse of California,” political consultant Andrew Acosta told me. “The next billionaire can pop up and say, ‘Hey, I’m gonna run.’ You don’t have that problem in Iowa.”

Maybe because of that, the people of California are uniquely inured to the star power of a very rich person. Central to Trump’s allure was the fact that he was a successful businessman, a television star; that he lived in big houses and dated beautiful women. In middle America, that is aspirational; in Los Angeles, that is the person you sit next to at brunch.

“Californians are so pummeled with these celebrities and these stars … that it doesn’t really grab people that someone running for public office also happens to be a celebrity,” said political consultant Gary South. Meaning, if you’re not a household name like Schwarzenegger or Reagan, don’t even try.

No surprise, then, that it is difficult to find a California politico who takes Cloobeck’s run seriously. I spoke to six consultants, advisers, and strategists for this story, and all of them laughed when I told them whom I was writing about. (“How did you manage to draw the short straw?” one asked.) The prevailing consensus is this: Here is another rich man, bored in his mega-mansion, who has been convinced by a cadre of greedy campaign consultants that he actually has a shot at winning. He will spend recklessly, make a few headlines, and eventually flame out and go back to hosting parties in Beverly Hills.

“If you’ve been around California politics for a long time, you’ve seen this act … of a rich person who’s gonna come fix Sacramento, because they’re the businessperson,” Acosta said. “It’s hot for a second, and then it fails miserably.”

This assessment, the political insiders say, is based on both personal experience with Cloobeck — one advisor told me the first time she met him, he talked at her so loudly and so ceaselessly that she literally retreated into a bush — and on the polling numbers, which don’t so much say something negative about Cloobeck as they don’t say anything at all. The latest polling on the governor’s race has Cloobeck at somewhere between 0% and 2%, leading one consultant to joke that the candidate is now a member of the 1% in more than one way.

And yet, no one was quite ready to count him out. It’s still early, they said. We can’t say anything for certain until after Prop 50, they said. We can’t make any predictions until we know if Caruso will run, they said.

What they meant was: It’s California. Who fucking knows.

The problem is that Cloobeck himself can’t define exactly why he should win. His pitch, when we meet, is littered with catchphrases he uses to describe himself — many of which he has actually trademarked — like “Californians are Customers™,” and “Equal or Greater Value™.” None of them cohere into a single message, which is likely a consequence of both the way he speaks — long, rambling, with lots of hand gestures — and the fact that he has not had a consistent campaign team for more than a few months. Cloobeck freely admits that he has had at least three campaign managers so far, and I can count at least as many communications directors.

But there is one theme Cloobeck likes to return to above all others, which is that he is a fighter for California. This is what voters want, he insists; this is why all of his campaign ads so far have been about Trump. He does not want to bore voters with endless policy proposals; he wants to show them he will stand up to the man whom everyone here so viscerally hates — including, if necessary, by making a campaign ad in which he talks about people being paid to handle the president’s balls.

This is also why Cloobeck keeps suing his fellow candidates. So far, he’s filed one suit against former L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a Democrat, for calling himself “a proven problem solver” — a phrase Cloobeck claims is too close to his campaign slogan, “I’m a proven problem solver” — and another against Republican Chad Bianco for wearing his official sheriff’s uniform at political events, in alleged violation of state campaign finance law. Bianco responded by accusing Cloobeck of pulling a stunt to boost name recognition; Villaraigosa has countersued, accusing him of trying to stifle political speech.

Cloobeck maintains that the suits were filed in good faith, a principled attempt to stand up for California’s laws. But he also insists that this mudslinging style is central to his appeal.

“Every other candidate is safe. I’m not safe,” he says. “I will be unapologetically authentic, and I will just tell it like it is: good, bad, indifferent.” Everything with him is always on the record, he tells me. (Which is true; he stays on the record even when I spot a pack of cinnamon flavored Zyns on his desk, which are illegal in California. He promises to bring them back if elected.) “That’s who I am,” he says. “I’m just here to tell the truth, have integrity, and make everyone’s world better.”

But sometimes the truth can be ugly, as is the case with multiple lawsuits Cloobeck has found himself embroiled in with ex-girlfriends.

The first is a suit he filed against model Stefanie Gurzanski in 2021, in which he alleges that he dated the then 26-year-old for six months before learning that she was secretly shooting content for OnlyFans. He sued for fraud, calling himself a “victim of a cunning serial fraudster” and alleging he’d spent more than $1.3 million on lavish gifts and trips for his ex. Gurzanski countersued, alleging that Cloobeck was manipulative and controlling — and well aware of her side hustle.

As their legal battle made its way through the courts, Gurzanski accused Cloobeck of threatening her, attempting to get her kicked out of her apartment, and repeatedly texting her in violation of a court-issued restraining order. (One text included in her application for a restraining order reads: “BTW. You are getting FAT.”) Cloobeck responded by telling a Vanity Fair (opens in new tab) reporter that Gurzanski was “not one of the top 10 blow jobs of my life, I’ll be honest.” They settled. The suits were settled out of court.

Another suit, which has not been previously reported, was filed against Cloobeck by a woman named Raven Armenta, who claims she was friends with him for 10 years before they started dating in 2023. She claims it started well, with Cloobeck showering her with money, clothes, and a Bentley Bentayga. But things went south that August, when she claims Cloobeck suffered a “psychotic break” fueled by alcohol and drugs — including large amounts of ketamine — and began accusing her of dealing drugs and attempting to extort him.

Armenta alleges that Cloobeck threatened to sue her or publish embarrassing articles about her if she did not give back the Bentley. Her suit includes a screenshot of a text purportedly sent to her by Cloobeck’s 22-year-old daughter, who apologizes for her dad’s behavior and writes: “He recently relapsed on alcohol and substance and he turns into a different person when he does. Truly I am so sorry you guys have to witness it. … The goal is to get him into rehab as soon as humanly possible.”

Armenta filed to dismiss the suit later that year. In a text message to The Standard, she said the case has been settled, and the two are “dear friends to this day.” Cloobeck told me the suit was “silly and stupid” and the result of a “lovers’ quarrel.”

“When you’re a wealthy man … people like to financially take advantage of that situation, and I won’t put up with it,” he added. “I mean, look at that Gurzanski lawsuit.”

I had asked Cloobeck about that lawsuit in September. I wanted to know if he thought it would harm his campaign, if he thought women would perhaps have trouble voting for a man who had commented publicly on his ex-girlfriend’s blow-job technique.

He did not.

“[Gurzanski] tried to extort me,” he told me. “I filed all those lawsuits because I don’t get extorted, and neither will anyone under my watch.” When you do well in business, he explained, people start to see you as a bank. Stephen Cloobeck is not a bank. Stephen Cloobeck is a fighter. “I will never get extorted, not for $5,000,” he said. “I’m gonna hold you accountable to integrity and law. I’m gonna fight those fights.”

In fact, he said — finally building to something resembling a campaign pitch — this is the whole problem with the Democratic Party today: It has become weak. It has lost its fight.

“I did not grow up in a Democratic Party that was weak,” he said. “I grew up in a Democratic Party that fought the good fight.” Clinton had taught him that; Reid had taught him that. Democrats were ethical; moral, he said, tapping the table for emphasis. “We fought for people. We did not shirk. We did not name-call.”

He paused here, perhaps realizing that this did not exactly square with telling your ex-girlfriend she is getting “FAT.” Then he added: “But if we have to, we gotta do it. If you gotta fight in the sandbox, you gotta fight.”

For all his bluster, Cloobeck can be remarkably consistent. One political consultant told me Cloobeck had been pushing to pause the landmark California Environmental Quality Act for years — long before Ezra Klein popularized the cause and politicians like Newsom made it a political imperative. Despite calling himself a “conservative Democrat,” Cloobeck is adamant about supporting abortion rights and opposing a Trump-style crackdown on immigration.

When we spoke in September, he told me repeatedly that he did not actually want to run; that he was only doing so because there were no other candidates he could endorse in good faith. At the time, I wrote this off as spin, a variation of a line often used to defend Trump: He didn’t have to run for office! He’s already so rich! As if the only incentives to seek higher office are monetary gain or pureness of heart.

But in Cloobeck’s case, the sentiment may have been genuine. When insiders started speculating last week that U.S. Rep. Eric Swalwell — whom Cloobeck knows personally, and has donated to in the past — may throw his hat in the ring for governor, Cloobeck was quick to praise his friend, citing his strong leadership and “brass balls.” He did not go so far as to say he’d drop out if Swalwell entered the race, but he came close enough.

“If I can find a better candidate, I will back a better candidate,” he told Politico. “If Eric’s that candidate, they will get my full-throttle balance sheet and intellectual capital and experience.” In a follow-up call with The Standard, he pledged his “16 months of due diligence” to any candidate he felt could pass muster.

Mike Madrid, an adviser to Cloobeck’s campaign, told me he had not been consulted on that pronouncement, but he wasn’t surprised. “He has always told me, ‘If there’s somebody better, who’s willing to challenge the way we’re doing things, I don’t need to be governor,’” Madrid said. “He is genuine when he says that; he means it. He’s not doing this for any personal aggrandizement.”

Earlier in our call, Madrid said there would be “a million Democrats or Republicans” who would “outright dismiss” Cloobeck for daring to run from the outside. The irony, however, is that these same establishment figures will be much less likely to dismiss Cloobeck if he drops out. Cloobeck has already spent $10 million on his own highly improbable campaign for governor. Imagine how much he could spend on a candidate who actually stands a chance. Imagine how much that could shake up the race.

That is the true power of a man like Cloobeck: Not to win a high-profile political race, but to decide who else might win it, by writing checks from the comfort of his Clooby cave. To use money as a proxy for power; to sway politics without having your nasty breakups used as oppo research or your campaign strategy turned into a punchline for political consultants. If not to own the governor’s mansion, then, at least, to time-share it, with all the other wealthy donors who backed the winning candidate.

In the end, Stephen Cloobeck may never become governor of California. But he will probably have a picture with the winner hanging on his wall.