Guillaume Garreau never expected to become an expert in family law — or in international child abduction.

Garreau, a software engineer from France, met Sana Onayeva, an international corporate lawyer from Kazakhstan, at a Bay Area expat meetup in 2019. They married in 2020, and their son, Maximilien, was born the following year.

Soon the relationship grew toxic. Garreau said Onayeva became verbally and physically violent toward him, and in February 2023, he filed for separation and a domestic violence restraining order. She filed a restraining order against him in turn.

Their case was assigned to San Francisco family court judge Daniel Flores. The appearances were stressful, Garreau said, but he found the judge to be patient and professional.

After hearings over six months that included hundreds of pages of evidence, audio recordings, sworn declarations, and examination of witnesses, Flores found that Onayeva had committed domestic abuse against Garreau.

Flores granted Garreau’s domestic violence restraining order and denied Onayeva’s, citing “significant credibility concerns” in her testimony and evidence, including an instance when she made false claims to law enforcement.

A civil finding of abuse is not a criminal conviction, but it affects parental rights. Garreau was awarded sole legal and physical custody of Maximilien, with Onayeva granted visitation.

A few months later, Garreau and Onayeva were back in court, at Onayeva’s request. She wanted permission to travel to Kazakhstan with Maximilien.

But their case had a new judge — Flores had been bumped up to handle civil trials and was replaced by Michelle Tong.

For Garreau, that marked the beginning of the end of life as he knew it.

Tong had no experience in family law, having spent most of her brief judicial career in small-claims court. She’d been assigned to the family court just four months prior, most likely because she lacked seniority. It happens all the time.

“Very few judges ask for family law — and it often falls on the newer judges, which is unfortunate,” said retired San Francisco judge Donna Hitchens.

In fact, the assignment to family court is so unpopular, according to those familiar with the bench, that it’s become a kind of judicial dumping ground — a place for new judges to cut their teeth or for problem judges to be quietly sent.

Family court judges decide where children sleep, how often parents can see their kids, and whether someone deserves protection from their abuser. The work is intense and high stakes, and the judges do it alone — with no jury, no prosecutor, and often no lawyers.

But with that extraordinary power comes little public accountability. Last year, family court judges drew more complaints than any other judicial division in California. But judicial complaints aren’t made public and almost never lead to discipline.

To understand how accountability works — and often fails — inside San Francisco’s family court, The Standard spoke with dozens of current and former judges, attorneys, and litigants, and reviewed court transcripts, filings, and judicial commission data. The picture that emerges is one of a secretive system in which judges wield extraordinary, often unchecked power over the defenseless.

For Garreau, the bureaucracy became a living nightmare.

Tong spent 17 years as an attorney for San Francisco’s public defender’s office before running for judge in 2020. She was initially assigned to small-claims court, then civil harassment — a position even less desirable than family court but with significant power. In one controversial decision in 2023, Tong denied a restraining order for a teenager who was being harassed by notorious serial stalker Bill Gene Hobbs. Hobbs was later sentenced to prison for a series of sexual assaults and battery on San Francisco women.

Garreau and Onayeva appeared before Tong for the first time in late November 2023. Before the hearing, Tong tentatively granted Onayeva’s request to take Maximilien out of the country.

In court, Garreau’s attorney, Abigail Morris, called Tong’s ruling “dangerous.” She reminded the court that Kazakhstan does not recognize the international Hague Abduction Convention, a treaty that allows for the swift return of a child wrongfully taken by a parent to another country.

“If Mother didn‘t come back with the child, Father would basically have no recourse to get his child back,” Morris told Tong.

Morris added that Onayeva had no job in San Francisco and had transferred $220,000 to her brother in Kazakhstan. “She has gotten rid of everything that would keep her here,” Morris told the court. “There’s just too much risk at this point.”

Tong ultimately denied the travel but granted Onayeva’s request for Garreau to pay her $20,000 in legal fees — essentially forcing a victim of domestic violence to pay legal fees to the abuser.

A month later, Onayeva again sought permission to take Maximilien to Kazakhstan, for what she said would be a two-week trip.

At the hearing in February 2024, Tong noted that Garreau’s attorney had previously “vehemently objected” to the trip. But this time, Tong said, she’d done her own research into Kazakhstan.

Despite the warnings and desperate pleas from Garreau and his attorney, Tong granted Onayeva permission to leave the country with the toddler.

“I have full faith and confidence that [Onayeva] will not only go and return; but, secondly, does not want to permanently reside there,” Tong said. “I could be wrong; maybe at some point in the future, but I don’t think it’s now.”

On March 16, 2024, Onayeva left for Kazakhstan with Maximilien. He was 2 years old. They never came back.

Onayeva was charged in the United States with child abduction and contempt of court. A warrant was issued, but there was no legal mechanism to compel her return.

Garreau has spent more than $250,000 trying to get his son back. After months of litigation in Kazakhstan, the court there ruled in January 2025 that Maximilien must be returned to the United States.

‘She got enabled by the judges and emboldened to keep violating every court order, keep committing perjury, and then abduct our son.’

Guillaume Garreau

In February, Garreau traveled to Kazakhstan with two investigators from the San Francisco district attorney’s office, but no one was at the address Onayeva had provided. Garreau has been back on his own to search for Maximilien and hasn’t found him yet.

Onayeva didn’t respond to requests for comment. Tong declined to comment through a representative of the court.

Garreau blames Tong for his son’s abduction. And he blames San Francisco’s family court for its lack of oversight and accountability of its judges.

“In family court, it seems that perjury has no meaning,” said Garreau. Onayeva “got enabled by the judges and emboldened to keep violating every court order, keep committing perjury, and then abduct our son.”

The last time Garreau saw Maximilien was a year ago, during a grainy 30-minute video call from Kazakhstan supervised by a therapist as part of a Kazakh court-ordered psychological evaluation.

“He didn’t know who I was,” Garreau said through tears.

Other litigants say they’ve felt the ripple effects of Tong’s decisions — and those of other San Francisco family court judges who operate with little oversight.

Jordana Cahen appeared before Tong in July 2022 while recovering from a beating by her ex-boyfriend that left her hospitalized with a fractured eye socket and broken nose. He also owed her nearly $7,000. Tong ruled that he needed to pay back only $555. Cahen said that when she asked for an explanation, Tong laughed. Cahen left the courtroom humiliated. A year later, a criminal court ordered her ex to pay her $32,000. He’s now serving a sentence of seven years to life for torture and abuse.

One mother went before Tong for a domestic violence restraining order to protect herself and her children from her ex. Tong denied the request and granted split custody. A follow-up hearing was reassigned to Judge Anne Costin, who severely limited the father’s visits.

A man said he was forced to move out of San Francisco due to continued harassment from his ex. The San Francisco Police Department suggested he file for a restraining order. Tong denied his request.

According to court records, Tong denied nearly half the requests that came before her. That is roughly 40% fewer restraining orders granted than the county average.

Garreau filed two complaints against Tong with the Commission on Judicial Performance, the state’s independent oversight body for judicial officers. The first complaint, filed after Tong ordered him to pay his ex-wife’s legal fees, was closed after the commission reported that it was unable to find “sufficient evidence to establish any type of judicial misconduct.”

Garreau’s second complaint remains under review nearly a year after submission.

The Standard reviewed three complaints against Tong provided by litigants. The CJP would not provide a total number or list of complaints against Tong or any other judge, saying it is not bound by the same open-record laws that apply to commissions overseeing public officers.

Complaints rarely lead to action. Last year, just 7% of the 1,718 complaints received by the CJP were investigated. Thirty-nine judges received some form of discipline, but the commission would release the names of only nine of them (opens in new tab). The rest received an advisory letter or “private admonishment.”

The last time a San Francisco judge was publicly disciplined was in 2008. That judge, James McBride, remained on the bench until his retirement in 2015.

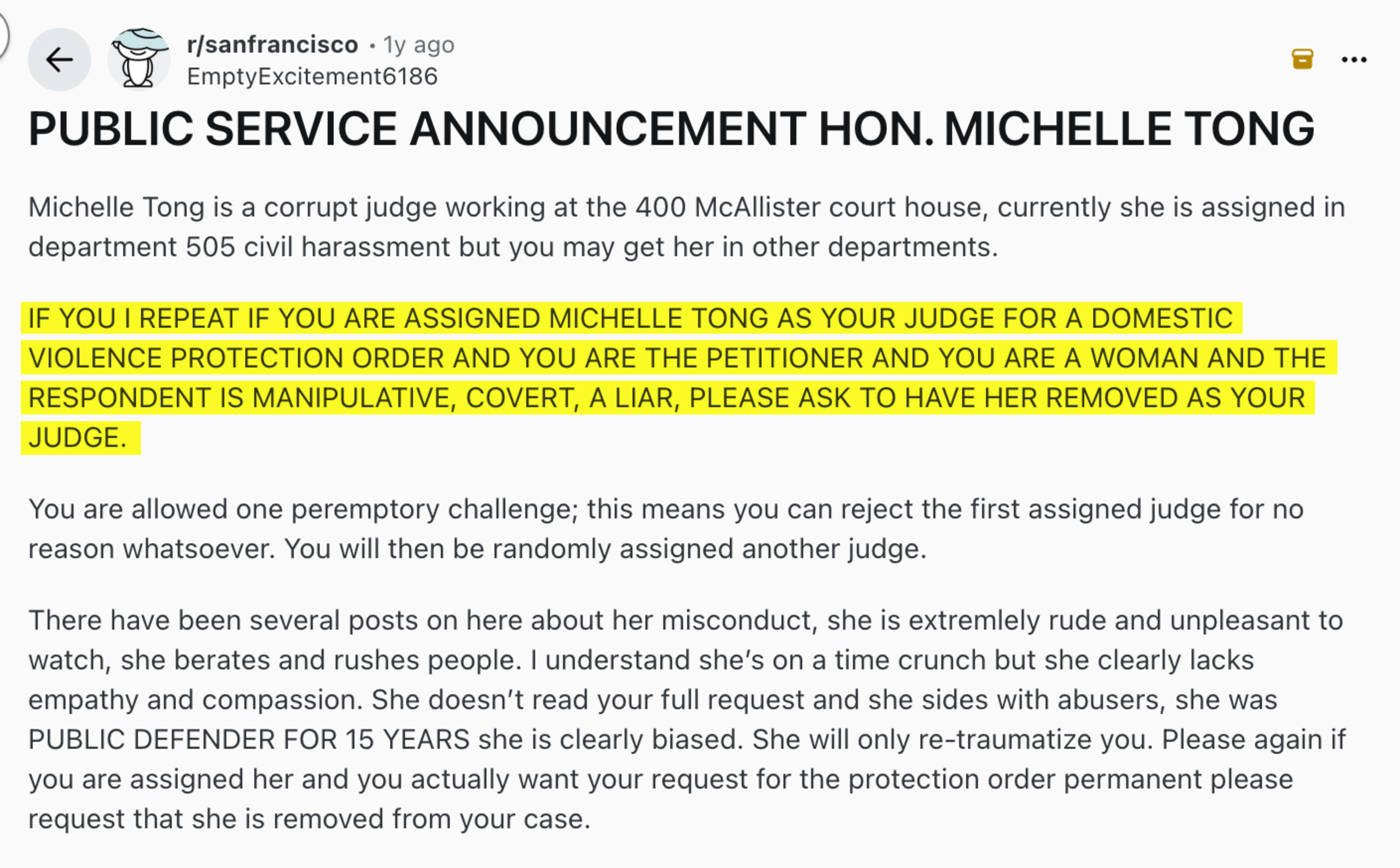

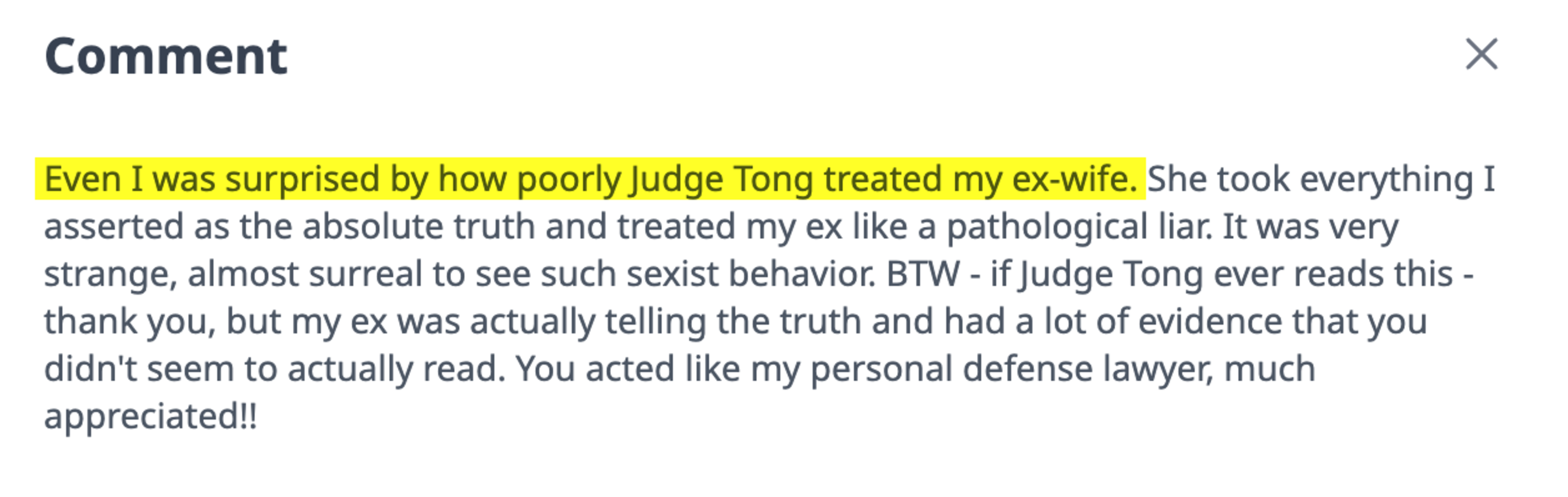

With so little transparency, litigants often turn to public forums, including Reddit and The Robing Room (opens in new tab), to warn others about judges’ behavior or commiserate over decisions they see as unfair.

The appellate process presents perhaps the clearest avenue for judicial accountability. But appeals take time and money, and few family court cases make it through the system. Most litigants can’t afford attorneys to argue their original cases, let alone to appeal.

One other option available to parties who believe a judge is ruling unfairly is a “peremptory challenge” — a formal request to remove the judge from the case. The challenge, based on the litigants’ belief that the judge cannot be impartial, must be filed at the start of the case, and self-represented litigants rarely know it’s an option. Family law attorneys said they tend to challenge sparingly, wary it might later be used against them in a court with so few judges on the bench.

However, in criminal court, the team at the San Francisco district attorney’s office under DA Brooke Jenkins has used peremptory challenges strategically to sideline judges they view as biased.

In June 2024, when Tong was briefly assigned to criminal court, the DA’s office filed 261 peremptory challenges against her — more than any other San Francisco judge in at least five years, according to Superior Court records. The coordinated challenges stalled Tong’s calendar and essentially forced her reassignment back to civil court. During her time in family court, Tong faced at least 40 peremptory challenges — an unusually high number, according to family law attorneys.

In August 2024, the DA’s office filed at least 80 peremptory challenges against Judge Carolyn Gold, forcing her reassignment — also to family court. Both moves further solidified the reputation of family court as a “dumping ground” for judges.

Gold spent much of her 30-year career representing tenants in landlord disputes in housing court before being elected to the bench in 2020. Until her assignment, Gold said, she’d never stepped foot in family court.

But she said she felt prepared, because as in landlord-tenant cases, most litigants are self-represented. “I do think it can be very empowering for a domestic violence victim to come to court on their own and tell their story and get their restraining order without a lawyer,” Gold said.

The view that survivors of domestic violence don’t need lawyers, and may even be better off without them, runs counter to what advocates have long argued. San Francisco voters agree; in 2022, they passed Proposition D to guarantee free legal representation for survivors of domestic violence.

Gold said she worries about fairness if victims have representation and alleged abusers don’t. “It’s concerning, because restraining orders have such serious consequences,” she said. “People can’t have a gun; it goes into the criminal justice system.”

A veteran family law attorney who recently litigated a restraining order trial in front of Gold said she plans to file a peremptory challenge if she’s assigned to the judge in any future case.

“I am appalled at her apparent lack of experience and training in domestic violence,” said the attorney, adding that the consequences of an untrained judge’s decisions can be severe. “It would be horrible for her to learn the hard way why protective orders should be granted, and not denied, when someone she lets go hurts someone.”

For all the complaints from litigants and attorneys about the judges in family court, some of the judges themselves might have complaints about the court too. The family court assignment is notoriously unpopular, primarily because of how labor-intensive it is.

“I did murder cases that were easier,” said Eugene M. Hyman, a retired Santa Clara County judge and domestic violence expert who spent more than 20 years rotating through assignments.

Last year, more than 3,500 cases were filed in San Francisco family court — a mix of divorce, domestic violence, and custody agreements spread across just four judges. That’s nearly 1,000 emotionally charged cases per judge, each involving a family in crisis.

Family court judges are often the first to arrive at the courthouse and the last to leave. Many work on weekends. Much of that time is spent reading — preparing to make decisions for each family that comes before them. Behind each 20-minute hearing are hundreds of pages of declarations and pleadings — sometimes lengthy briefs from attorneys, sometimes handwritten declarations from litigants.

Most judges understand the weight of the assignment.

“This might be one of dozens of cases that we may have each day, but for the family that we‘re seeing, this is their only case,” said Judge Monica Wiley, the rare jurist who has chosen to spend most of her 16 years on the bench in family court. She now oversees only the most complex family law litigation. “The decisions that we make are going to have lifelong impacts upon their families and their children.”

When judges do get it right, it can make a profound difference to litigants, especially victims of domestic violence who turn to family court as a last resort.

One woman, whose husband’s criminal case was dismissed by the district attorney despite him nearly killing her, said she saw a rare glimpse of humanity in the bureaucracy when Judge Russell Roeca approved her restraining order. “He looked me right in the eye, and he said, ‘I want you to know, I’m so sad this happened to you,’” she recalled. “Those couple of words meant so much to me.”

The family court bench is checked primarily by Rochelle C. East, San Francisco’s presiding judge, who makes judicial assignments and determines if there is inappropriate judicial bias.

“Presiding judges of the court have a responsibility to be aware of the pulse of their judges,” said Hyman. The retired Santa Clara judge added that if he were in charge, he would provide Tong with more training and mentorship before determining whether there’s an education problem or an ethics problem.

‘Judges, they are elected public servants. They’re paid by our taxes. They are state employees. We should have total transparency.’

Guillaume Garreau

“The fact that she has ruled a certain way that people don’t like is not in and of itself a violation of ethics. But it’s when you have a pattern of doing it that you get concerned,” he said.

Besides reassigning courtrooms, “sometimes, unfortunately, the only potential remedy you have is to have someone run against them,” he noted.

As of July 2024, Tong had been assigned away from family court, taking over civil harassment and traffic responsibilities — two of the least desirable, if not punishing, positions for a judge. She’ll be up for reelection in November 2026.

Garreau regularly calls the California Commission on Judicial Performance to check up on his second complaint against Tong. On Oct. 24, nine months after he submitted the complaint, he received a curt letter.

“This matter is under consideration,” the commission said.

He believes the commission is stalling. “They’re just waiting until next year, hoping she doesn’t get reelected. Then they can say, ‘Oh, she’s not a judge anymore’ and sweep it under the rug.”

For Garreau, and the thousands of San Franciscans whose lives have been altered by decisions made by family court judges, the system of accountability is unacceptable.

“Judges, they are elected public servants. They’re paid by our taxes. They are state employees. We should have total transparency,” said Garreau.

“How is it possible that after everything that happened — after she let this happen — she’s still sitting on the bench?”