Rachel Harrison was 17 weeks pregnant in September 2024 when she felt a strange sensation: her water breaking. Then she saw blood.

Her boyfriend, Marcell Johnson, helped her to the car and drove to the closest hospital covered by their insurance: Mercy San Juan Medical Center, outside Sacramento.

“Our goal was just to get help,” Harrison remembered. “Have them save our baby.”

After they’d spent four hours in the emergency department, an ultrasound confirmed the worst: Her water was fully broken, and there was no way to save the pregnancy.

“My whole world was flipped upside down,” Johnson said. “It broke me.”

A miscarriage at 17 weeks is not just devastating — it can be fatal for the pregnant person. The medical term for Harrison’s condition is previable PPROM. Standard care calls for an emergency procedure to terminate the pregnancy and protect the woman’s health.

Instead, the physicians at Mercy told Harrison and Johnson something they couldn’t comprehend: She was being discharged to miscarry at home.

“They told us because of their religious beliefs and because there was still a heartbeat that there was nothing that they could do,” Harrison said.

The couple had no idea that Mercy was a Catholic facility — and that this would dictate the availability of maternal medical care.

“A hospital, to me, is just a hospital,” Harrison said. “You go there to get help.”

What she encountered that day was not a one-time mistake. It was policy — the result of religious directives that govern nearly 1 in 3 hospital beds in California.

Mercy San Juan is part of the San Francisco-based Dignity Health network, the largest hospital system in California. Dignity hospitals follow the Ethical and Religious Directives written by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. The rules restrict care for a miscarriage if there is fetal cardiac activity. That means a detectable heartbeat can override medical judgment and best practices.

Mercy San Juan discharged Harrison with instructions to let the second-trimester miscarriage unfold at home, despite the fact that she was at serious risk of infection.

Johnson’s grief was compounded by the shock. “What do we do with the baby afterward — throw him away in the trash?”

At home, her contractions worsened. It wasn’t just labor pain — she felt that something was truly wrong. She rushed to Kaiser, a secular hospital, where clinicians immediately recognized the danger: She was bleeding and at risk of sepsis. Without the care of those doctors, she might have died.

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, California has protected abortion rights on paper (opens in new tab), positioning the state as a national refuge for maternal care (opens in new tab). But at the Catholic facilities that represent many of the state’s largest hospital systems, those protections disappear the moment a patient walks through the door.

Across the country, abortion bans have made life-saving maternal care dangerous and lethal — women have died in Texas (opens in new tab) and Georgia (opens in new tab) while being denied basic healthcare. Despite California’s progressive policies, pregnant patients are at risk of the same fate when their hospitals follow religious directives over state law. With Attorney General Rob Bonta taking up the issue, emergency maternal care is likely to become a defining legal fight.

Over the last 15 years, Catholic health systems have expanded dramatically across California through mergers, acquisitions, and management contracts. Staff at these facilities now deliver roughly 17% of all babies born in the state.

In wide swaths of California, particularly in rural regions, these are the only hospitals. A 2023 study from UCLA (opens in new tab) found that seven California counties rely exclusively on faith-based hospitals, and in 17 others, religious hospitals hold a majority of the market.

Few patients know they are entering facilities governed by religious rules until the moment they are denied care. A 2018 national survey (opens in new tab) found that more than a third of women whose primary hospital was Catholic did not know about the religious affiliation.

Lori Freedman, a UCSF sociologist and bioethicist who has spent nearly two decades studying Catholic maternal health practices, said cases like Harrison’s are difficult to track because they often are not reported in medical records or to regulators.

“The ‘how common’ question is the hardest,” she said. “But what I found is that OB-GYNs are very worried about this. It’s extremely frustrating to practice under rules that can delay care.”

Freedman said most physicians she has interviewed don’t agree with their hospital’s Catholic directives and have developed quiet workarounds — rushing patients to secular facilities or calling ethics committees to obtain special permission to act.

“But the rules are always there in the background — and sometimes they stop care that should be routine,” she said. “There’s always a risk that someone will follow the directives strictly and leave a patient vulnerable.”

Harrison found out she was pregnant again on Christmas Eve in 2024.

The couple were hopeful but wary. They had grieved deeply. Johnson had stopped drinking and picked up fishing, something quiet and steady to help him cope. At around 16 weeks, they could feel the fetus kick — strong, insistent movements that made the pregnancy real. They named her Jamera, a combination of their mothers’ names. They talked to her every night and bought a fetal doppler to listen to the heartbeat.

But then it happened again.

At 17 weeks, Harrison’s water broke — suddenly, completely — just as it had in her first pregnancy. This time, she and Johnson refused to go back to Mercy San Juan. They drove instead to Mercy General, another Dignity Health hospital 13 miles away.

They did not know it was governed by the same religious rules.

An ultrasound showed the fetus had a heartbeat. The staff said the same thing she had heard a few months earlier: There was nothing they could do.

They discharged her. The couple knew to drive straight to Kaiser.

There, clinicians acted immediately. Harrison was contracting and losing blood. She was admitted and given options: Terminate the pregnancy now, or wait it out with the goal of reaching 22 weeks — the threshold at which a baby might survive with intensive care.

Harrison was born four months early, weighing 1 pound. If she made it, maybe her daughter could. “We said we were going to wait it out,” she said. “Pray and hope she could make it.”

Harrison was transferred in an ambulance to Kaiser Roseville for continuous monitoring. But by the time she arrived, the fetus’ heart had stopped.

What followed was a cascade of medical complications that the Catholic hospitals could likely have anticipated and prevented. Harrison lost significant blood. She went into sepsis — a life-threatening response to infection. It was exactly the kind of complication that standard obstetric protocols are designed to prevent, and the reason physicians don’t typically send patients home to miscarry. She needed a blood transfusion.

But unlike at the Catholic hospitals, Harrison was not sent home. Kaiser gave the couple a room in the labor and delivery unit. They were given a tiny pink dress, a hat, and a blanket. They held their deceased daughter, who was barely the size of a doll. They took photographs. She stayed with them for three days in the hospital room as Harrison recovered.

“Even though she was gone, we got to see what we created,” Harrison said. “It was so special.”

Everyone said she looked like Harrison’s twin.

“She had a big old head like me,” Johnson said through tears. “She was so cute.”

In September 2024, around the time Harrison was denied care at Mercy San Juan, Bonta sued a different Catholic hospital (opens in new tab) — Providence St. Joseph in Humboldt County — alleging that it refused to treat pregnant patients facing life-threatening complications for religious reasons. The attorney general called Providence St. Joseph’s policies “draconian.”

One patient who was later added to the lawsuit was forced to wait while staff monitored her for sepsis, despite a nonviable pregnancy and signs of infection. Providence St. Joseph denied her care during a pregnancy in 2021 and again in 2022. Another patient, physician Anna Nusslock, was denied a medically necessary termination even as she faced what the AG later described as an “immediate threat to her life and health.”

“People in California assume this doesn’t happen here,” said K.M. Bell, senior counsel at the National Women’s Law Center, which is representing Nusslock in a separate civil suit.

Bell said many refusals of care are never communicated to the patient. “Typically, somebody is left sitting in a hospital bed, bleeding and in pain, without care being provided — and they don’t even know why.”

Providence St. Joseph is the only labor-and-delivery hospital for miles. “In this community, there are no alternatives,” said Bell. “Patients were being told they needed to be helicoptered to San Francisco.”

When Bonta secured a stipulation that required the hospital to provide stabilizing emergency care, Providence attempted to introduce a policy allowing intervention only if it was the “only alternative to certain death.” State lawyers argued that the standard would violate California’s Emergency Services Act, which requires hospitals to treat emergencies before a patient becomes critically ill.

In recent legal filings, Providence has argued that it does not need to comply with the law because of its religious beliefs, which it says are constitutionally protected. Legal experts say that argument might be hard to prove in California, where strong civil rights laws generally don’t grant religious protections. But some warn that litigating these cases in California may be part of a longer legal strategy. If the cases make their way to federal courts by way of appeals, they’ll likely find an audience far more receptive to claims of religious liberty.

A representative for Providence said the hospital disputes the AG’s version of events and contended that its treatment of patients was medically appropriate. “Providence remains deeply committed to ensuring that pregnant patients receive timely, compassionate emergency care,” the spokesperson said.

The next hearing in the AG’s case is scheduled for Dec. 10. California’s Department of Justice is wrapping up a statewide survey (opens in new tab) to assess how hospitals are complying with emergency reproductive healthcare laws, specifically when abortion is deemed medically necessary.

The Humboldt cases have become a test of how far California can go in enforcing reproductive rights within hospital systems governed by religious doctrine. They also show how easily patients can be denied life-preserving care when Catholic hospitals are a region’s only medical providers.

“It’s a really scary proposition for the community,” said Bell.

After their second loss, Harrison and Johnson decided to seek legal help.

“The way we were treated just wasn’t right,” Harrison said. “I’m helpless, I’m trying to save our babies, and they didn’t take it seriously. They failed me. They failed our kids.”

Their lawsuit, filed in September in San Francisco Superior Court, alleges that Mercy San Juan and Mercy General violated California’s Emergency Services Act — the same law at issue in the Humboldt case — and failed to provide stabilizing care, based solely on religious restrictions. It also alleges discrimination under the state’s civil rights law.

“For them to tell us to go home and pass our babies naturally — that’s inhumane,” Johnson said. “I want the whole world to know what they did to us.”

In response to questions about Harrison and Johnson’s care, a dignity Health spokesperson said that “when a pregnant woman’s health is at risk, appropriate emergency care is provided,” adding that the hospital network is “committed to providing the highest quality, compassionate care to every patient.”

The couple’s case could help determine whether religious health systems can continue to operate under policies that conflict with state requirements for emergency care. It places Harrison and Johnson among a growing movement of patients challenging the gap between California’s reproductive rights laws and the reality inside many of its largest hospitals.

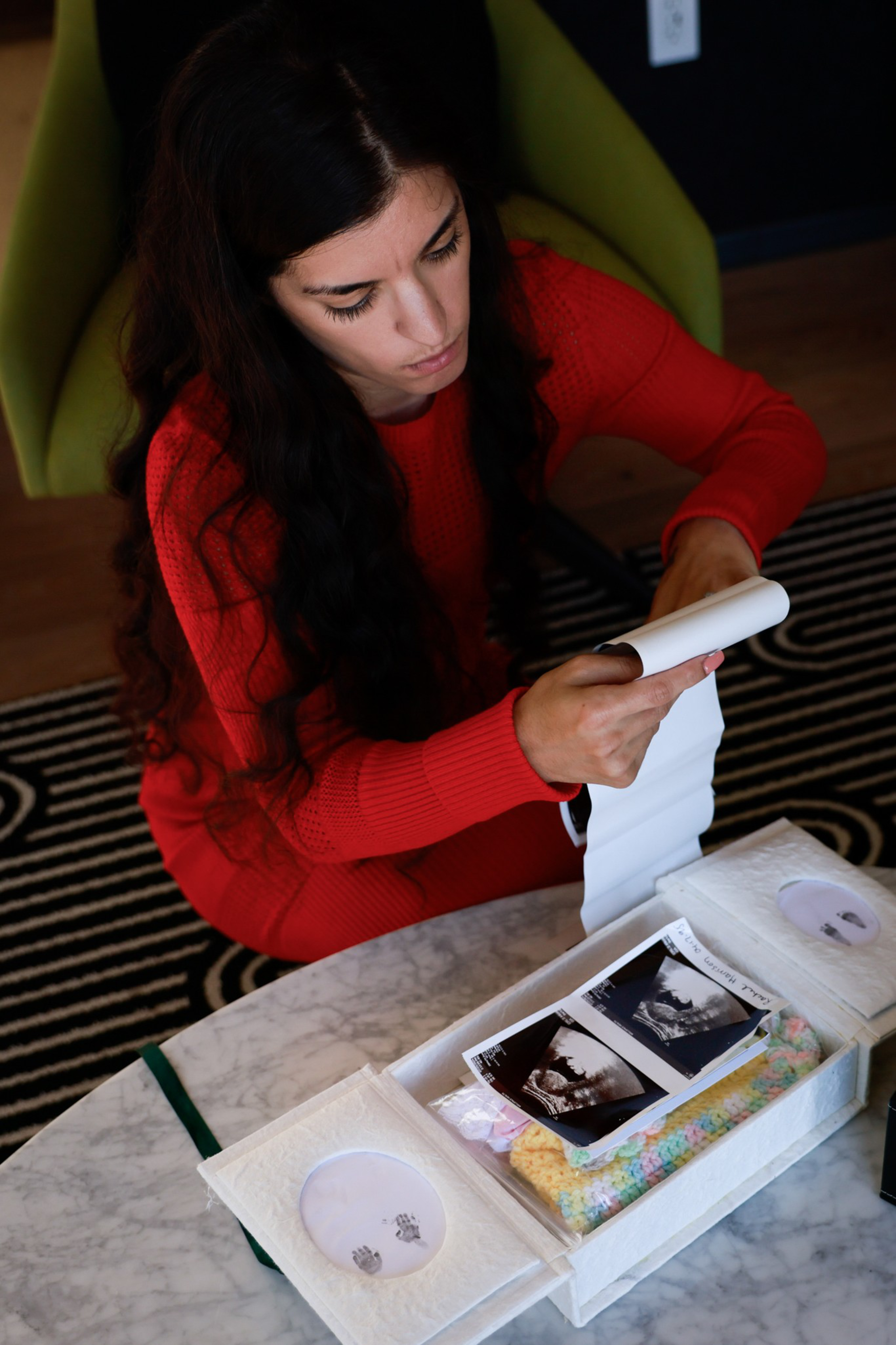

The couple keeps a memory box for Jamera — the tiny hat, the pink dress, the blanket.

But Harrison rarely opens it.

They still want to become parents. “We’ll keep trying. We won’t give up,” she said.

Freedman is grateful Harrison and Johnson were willing to go public with their case and hopes it will force a reckoning around practices at Catholic hospitals. “It’s just a horrendous thing to go through. And I think that the reason this hasn’t been dealt with is because there’s so much stigma and vulnerability around talking about a pregnancy loss,” she said.

“I hope that it will make all the Catholic hospital systems of California communicate more transparently about what their plan is for patients like this. And if they don’t have a good plan, I want them to also communicate that to their potential patients and consider incorporating really clear counseling about where prenatal patients are supposed to go if they’re having pregnancy trouble,” she added. “And that is probably not a Catholic hospital.”