Every city has its convenience store charms. New York’s bodegas serve below-par bagels. Chicago markets sell local liquor Malört for an always-at-hand hangover cure. New Jersey has Wawa hoagies, a concerning point of pride for a state that just needs…something.

READ MORE: San Francisco $18 Bread: We Tried the Purple ‘Playful Sourdough’ Everyone’s Talking About

In San Francisco, we have baklava.

I noticed the flaky pastries front and center at local check-out counters immediately after moving to the city. It probably helped that they’re one of my favorite desserts and that I live in the Richmond District, home to Little Russia and countless Middle Eastern-influenced eateries.

But I had also seen the sweet squares at markets outside my immediate neighborhood and had a suspicion that there was a bigger trend at play. Thus began my investigation.

I started by Googling “baklava near me,” but that just turned up nearby Mediterranean restaurants. I wanted to know about the city’s underground baklava scene—and to find out who is supplying local corner stores with the sweet pastries.

Hearing about my investigation, one colleague told me she had seen a sign for what looked like a baklava popup on Harrison Street while biking to work. Now that seemed promising. So I went.

What I discovered was San Francisco’s newest baklava chef—and an entrepreneur taking the baklava scene by storm.

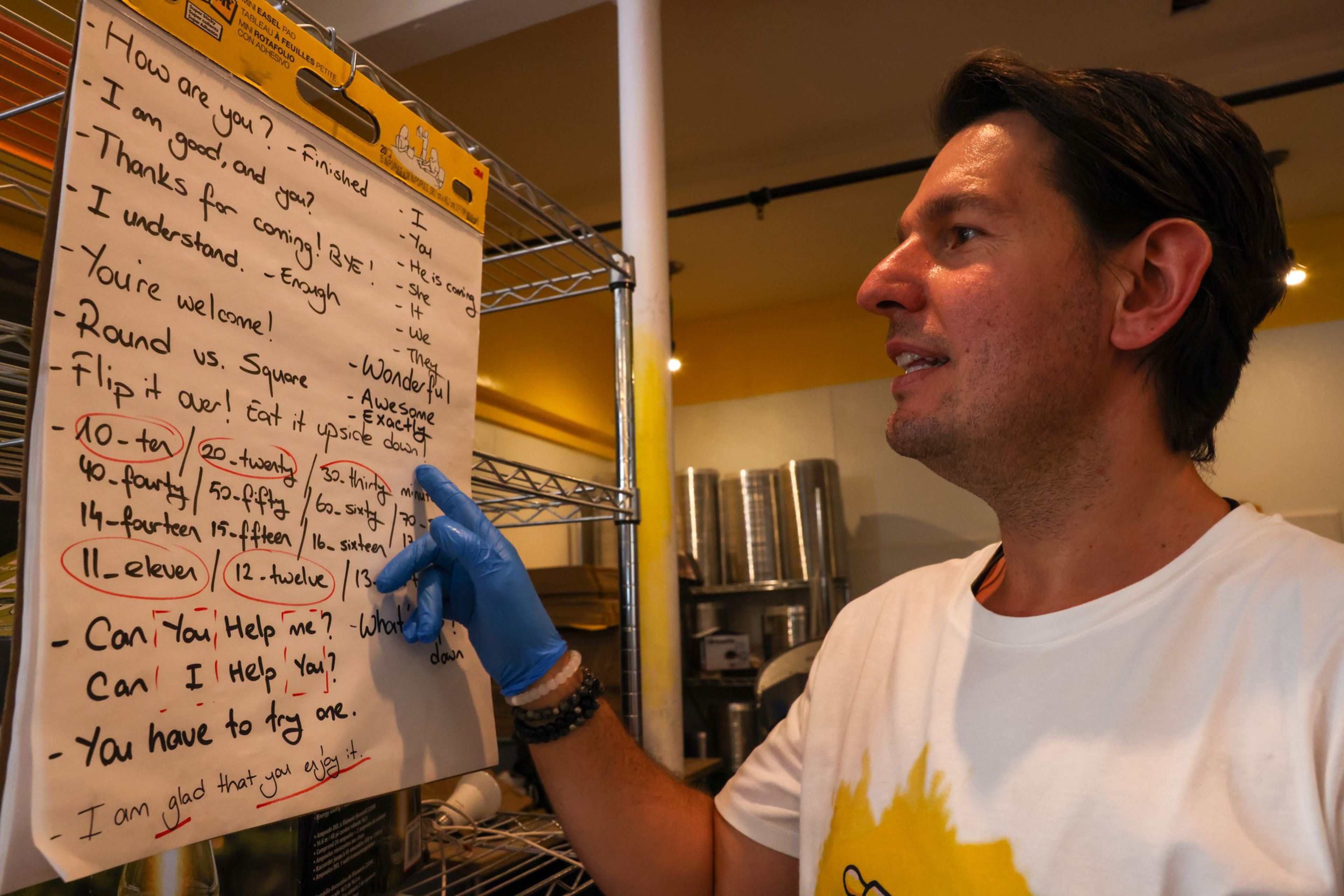

Tolgay Karabulut’s love for baklava emanated from his smile, the way he handled the slippery butter and the paper-thin layers of filo, and how he talked excitedly about his upcoming trip to Turkey to harvest more pistachios—about a month before the typical harvesting season, when they’re at their juiciest. A Turkish immigrant with a Greek mother and Macedonian father, Karabulut arrived in the United States in 2009 and found “zero good baklava,” much to his dismay.

“It’s not to my taste,” Karabulut said diplomatically.

So Karabulut spent four years traveling across the Middle East, Turkey and Greece to learn from the best chefs and to find the best ingredients.

He opened Baklavastory (opens in new tab) in the Mission District just three months ago, and now has partnerships with four restaurants in the city. Karabulut arrives at 5:30 a.m every day—except Sunday—to prep and bake his baklava alongside co-chef Harun Sert for takeout orders only. But he’s always got a tray ready for tasting. About halfway through our interview, a woman stumbled upon the shop. Just one nibble off a fresh square, and it was obvious she’d be back.

Karabulut said it all comes down to quality ingredients.

His ghee butter is milked from Turkish sheep two weeks after they’ve eaten the first spring grasses. Also from Turkey are his flour and wheat starch, used to make the 40 layers of filo in each batch puffy. His eggs come from Petaluma, and his walnuts and almonds are California grown, too. But he said he’d go anywhere in the world to find the best.

“I told my mom, ‘This is my love,’” he said.

Other Bay Area locals, like Hatice Yildiz of Simurgh Bakery who sells at the Ferry Building, are taking a similarly artisanal approach.

There’s also Bitchin’ Baklava (opens in new tab) in the outer Richmond, which is currently supplying its crunchy sweets to the de Young Museum during the run of the Ramses the Great exhibition. Other local restaurants import their baklava from abroad, like Yumma’s Mediterranean Grill in the Sunset and Aegean Delights in the Castro.

“I don’t feel like they’re really my competitors,” Bitchin’ Baklava owner Sausan Molthen said of the wholesale baklava sellers, which often add preservatives and use frozen dough to sell to local grocers. “They make it with machines. I make each tray individually.”

Yildiz agreed, pointing to one controversial brand in particular. Diamond Bakery, she said, uses cheap ingredients and sells baklava for just a few dollars per package, forcing everyone else to lower their prices, too.

“I have sons; they are from Yemen and they said, ‘Even you cannot feed cows with this baklava in Yemen,’” Yildiz said. “I wish the best to them, but they damage the whole baklava market. They have a monopoly.”

With new insights into the Bay Area’s baklava battles, I went out to some of my go-to local hookups, like Golden Bear Trading Company. Ed Lee, the new owner, took over the shop three years ago from a Palestinian, learning how to make—and appreciate—the spiced coffee. But the baklava he buys is from Diamond Bakery, which Lee said supplies many of the local markets.

“He’s got a little mini empire,” Lee said of Diamond’s owner.

Down the road, I stepped into JT Market. Mostly a liquor store, it also sells snacks and lottery tickets. At first I didn’t see the telltale plastic containers, so I asked owner Nabil Hanhan if he sold baklava. He said, “of course.” It was also from Diamond.

After a third shop owner identified their supplier as Diamond, I knew I had to get in touch with the company.

The phone rang for almost a minute before the line to Diamond Bakery’s Fremont factory location disconnected. The second time I called, someone picked up but then hung up after a few seconds of silence. The third time, I got owner Adel Mougharbel on the phone. He agreed to talk to me later in the week. My heart fluttered a little bit at the idea of finally getting to interview the Bay Area’s baklava baron.

But in the meantime, I was getting a slice at Lavash with its owners Nazila and Saeed Talai, who welcomed me in for tea and waited patiently for my first bite of dessert before diving into the details.

To Nazila, the answer to my burning questions about the absolute chokehold baklava has on the neighborhood was simple: “My mom used to make it. Every mom from the old culture, they make it for you.”

This was the most common, and likely the most scientific, explanation I would receive. Baklava is unique yet universal, spanning many cultures, each of which has its own take on the dessert. Lavash’s is baked with signature Persian flavors of rosewater and saffron. But each seller I met told me most of their customers don’t come from a baklava-eating background. The flaky, crunchy, buttery, sweet dessert has wide appeal.

The local popularity of the dessert has come as a shock to a lot of its chefs and sellers. But Mougharbel, when I finally got him on the phone, wasn’t surprised.

Originally from Lebanon, his parents established the business in 1990 in San Mateo before it moved to Fremont, distributing baklava all the way from Sacramento to San Francisco, including at stores like Restaurant Depot. I went by and sure enough, there they were: golden labels shining all in a neat little row.

His competitors have come and gone, Mougharbel said, but he attributes Diamond’s ongoing success to the consistent quality of the baklava and also to his customer service: Mougharbel said he gets calls all the time from customers who have something to say—good or bad—about a batch.

As to the critics, he was not fazed. Homemade and commercial baklava are fundamentally different products, he said. In any case, Mougharbel doesn’t believe it’s possible to make a real profit off freshly baked baklava using expensive imported ingredients—and warns new chefs to be careful about asking for top dollar.

But mostly, as San Franciscans’ insatiable hunger for baklava grows, he said he welcomes the newcomers.

“The market is big enough for both of us,” Mougharbel said.